Stories in the Website

This page contains: four stories from my life; the joy of science,

from science history; three

illustrative examples; a

set of four fictional dramas about creation, evolution, and design.

Below are four true stories from my own experience:

Understanding

and Respect

Students in my high school learned

valuable lessons about understanding and attitudes from one of our favorite

teachers,

who sometimes held debates in his civics class. On Monday he convinced

us that "his side of the issue" was correct, but on Tuesday he

made the other side look just as good. After awhile we learned that,

in order to get accurate understanding, we should

get the best information and arguments that all sides of an issue can claim

as support. After we did this and we understood more accurately and

thoroughly, we usually recognized that even when we have valid reasons for

preferring one position, people on other sides of an issue may also have

good reasons, both intellectual and ethical, for believing as they do, so

we learned respectful attitudes.

But respect does not require

agreement. You

can respect someone and their views, yet criticize their views, which you

have evaluated based on evidence, logic, and values. The intention

of our teacher, and the conclusion of his students, was not a postmodern

relativism. The goal was a rational exploration and evaluation of

ideas in a search for truth. { the

page continues by explaining how these

principles are used in the website }

A "Cliffs

Notes" Approach

This section explains how — in

three decisions and a library — I recognized the similarity between Cliffs

Notes and the introductory

level of the ASA Science Ed website.

The first two decisions were easy. Yes,

I would watch the movies. No, I would not read the books. In either

form, in movies or books, Lord of the Rings is a classic. Although

I

would

enjoy

reading

the

trilogy

by

Tolkien, "time is the stuff life is made of" and I decided that reading

three large books would not be a good use of my time. But reading one small

book would be quick and useful, so I decided to read the summary/analysis written

by Gene Hardy for Cliffs Notes. And having an introductory overview of "the

big picture" — provided by Hardy's summary of the three books — helped

me

understand

and

enjoy

the

three

movies.

In the two weeks between seeing the

first

movie (on DVD) and second movie (in theater) I attended the Following

Christ conference. It was organized by InterVarsity Christian Fellowship,

and included a temporary library of books by InterVarsity Press. While

browsing the tables filled with high-quality books, reading the back covers,

table of contents, and occasional pages, I thought about the many fascinating

ideas I would miss because I wouldn't be able to invest the time needed to read

these books. I

was also thinking about Lord of the Rings and the practical educational

value of reading one small book instead of three large books, and I made the

connection

between

booktable and website. It would be useful for me to have a condensation

containing the distilled essence of important ideas from books on the table,

and giving you "a condensation containing

the

distilled

essence of important ideas" is the goal of the introductory pages in

this

website. { from A Quick

Education }

Learning

from Experience (how to excel at welding or...)

One of the most powerful master

skills is knowing how to learn. The ability to learn can

itself be learned, as illustrated by a friend who, in his younger days,

had an interesting strategy for work and play. He worked for awhile

at a high-paying job and saved money, then took a vacation. He was

free to wake when he wanted, read a book, hang out at a coffee shop, go

for a walk, or travel to faraway places by hopping on a plane or driving

away in his car.

Usually, employers want workers

committed to long-term stability, so why did they tolerate his unusual behavior? He

was reliable, always showed up on time, and gave them a week's notice before

departing. But the main reason for their acceptance was the quality

of his work. He was one of the best welders in the city, performing

a valuable service that was in high demand and doing it well. He could

audition for a job, saying "give me a really tough welding challenge

and I'll show you how good I am." They did, he did, and they hired

him.

How did he become such a good welder? He had "learned how to learn" by following the wise advice of his teacher: Every time you do a welding job, do it better than the time before (by learning from the past and concentrating in the present) and always be alertly aware of what you're doing now (and how this is affecting the quality of welding) so you can do it better the next time (intentionally learn from the present to prepare for the future). This is a good way to improve the quality of whatever you do. Always ask, "What have I learned in the past that will help me now, and what can I learn now that will help me in the future?", while concentrating on quality of thinking-and-action in the present.

This is from the same page (about Motivations & Strategies for Learning) as this:

How

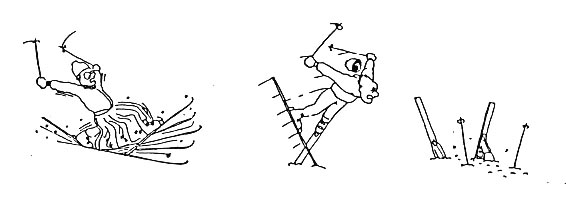

I Didn't Learn to Ski (by Learning from Mistakes)

My first day of skiing! I'm excited,

but the rental skis worry me. They look much too long, maybe uncontrollable? On

the slope, fears come true quickly and I've lost control, roaring down the

slope yelling "Get out of my way! I can't stop!" But

soon I do stop — flying through the air sideways, a floundering spin,

a mighty bellyflop in icy snow. My boot bindings grip like claws that

won't release their captive, and the impact twists my body into a painful pretzel. Several

zoom-and-crash cycles later I'm dazed, in a motionless heap at the foot of

the mountain, wondering what I'm doing, why, and if I dare to try again.

Even the ropetow brings disaster. I

fall down and wallow in the snow, pinned in place by my huge skis, and the

embarrassing dogpile begins, as skiers coming up the ropetow are, like dominoes

in a line, toppled by my sprawling carcass. Gosh, it sure is fun to ski.

With time, some things improve. After

the first humorous (for onlookers) and terrifying (for me) trip down the

mountain, my bindings are adjusted so I can bellyflop safely. And

I develop a strategy of "leap and hit the ground rolling" to

minimize ropetow humiliation. But my skiing doesn't get much better

so — wet and cold, tired and discouraged — I retreat to the

safety of the lodge.

How I Did

Learn to Ski (Insight and Practice, Perseverance

and Flexibility)

The lodge break is wonderful,

just what I need for recovery. An hour later, after a nutritious

lunch topped off with delicious hot chocolate, I'm sitting near the fireplace

in warm dry clothes, feeling happy and adventurous again. A friend

tells me about another slope, one that can be reached by chairlift, and

I decide to "go for it."

This time the ride up the mountain

is exhilarating. Instead of causing a ropetow domino dogpile, the

lift carries me high above the earth like a great soaring bird. Soon,

racing down the hill, I dare to experiment — and the new experience

inspires an insight! If I press my ski edges against the snow a certain

way, they "dig in." This, combined with unweighting (a

jump-a-little and swing-the-skis-around foot movement) produces a crude

parallel turn that lets me zig-zag down the slope in control, without runaway

speed, and suddenly I can ski!

Continuing practice now brings

rapidly improving skill, and by day's end I'm feeling great. I still

fall down occasionally, but not often, and I'm learning from everything

that happens, both good and bad. And I have the confident hope that

even better downhill runs await me in the future. Skiing has become

fun! { In the

full page this experience is used to illustrate two principles for learning:

Insight

and Quality Practice, Perseverance and Flexibility. } {cartoon by

Frank

Clark, 1982}

The welder and skier stories (above) are in my "Motivations and Strategies"

page, and between them is this true story from the history of science, about

the joy of science:

It's fun!

Personal goals for learning can include improving skills (like

welding or thinking) and exploring ideas. One powerful motivating

force is a curiosity about "how things work." We like to solve

mysteries.

The joyful appreciation of a challenging

mystery and a clever solution is expressed in the following excerpts from letters

between two scientists

who were intimately involved in the development of quantum mechanics: Max

Planck (who in 1900 opened the quantum era with his mathematical description

of blackbody

radiation) and Erwin Schrödinger (who in 1926 wrote and solved a "wave

equation" to

explain quantum phenomena). Planck, writing to Schrödinger, says "I

am reading your paper in the way a curious child eagerly listens to the solution

of a riddle with which he has struggled for a long time, and I rejoice over

the beauties that my eye discovers." Schrödinger replies by agreeing

that "Everything

resolves itself with unbelievable simplicity and unbelievable beauty, everything

turns out exactly as one would wish, in a perfectly straightforward manner,

all by itself and without forcing." They struggled with a problem, solved

it, and were thrilled. It's fun to think and learn! { You

can learn more about the joy of science and "waves that are particles

and particles that are waves" and how

Planck and Schrödinger (and Einstein and others) solved the mystery. }

Here is a metaphor and two illustrative

examples, which are similar to stories:

Goal-Directed

Education

Aesop's Fables are designed to achieve

a goal, to teach lessons about life. By analogy, goal-directed Aesop's

Activities can help students learn ideas and thinking skills. In a goal-directed

approach to improving education, the basic themes are simple: a teacher

should provide opportunities for educationally useful experience, and help

students learn more from their experience.

Is

methodological naturalism required by The Rules?

A theory of intelligent design acknowledges the

possibility

of

divine action, so it violates a rigid methodological naturalism (MN) and thus,

according

to some people, it violates "the rules of science."

Is

science a game with

rules? This is an interesting perspective. In terms of sociology,

regarding interpersonal dynamics and institutional structures, it is an idea

with merit. But it seems less impressive and less appealing when we think

about functional logic and the cognitive goals of science. It seems more

logical to view science

as an activity

with

goals (which include searching for truth) rather than a

game

with

rules (which include the restrictions imposed by rigid-MN).

Let's compare "cheating" in

sports,

business, and science. In a Strong Man Contest, if other contestants carry

a refrigerator on their backs, one man should not be allowed to move it using

a two-wheel cart because this is not useful for achieving the goal of the game,

for determining who is the strongest man. But if the goal of a business

is to move refrigerators quickly, many times during the day, a two-wheeler is

useful.

Although it isn't the only goal,

for most scientists the main goal of science is finding truth about nature. But

a rigid-MN might lead to unavoidable false conclusions. When some scientists

recognize this and decide to reject rigid-MN, is it cheating or wisdom? Is

adopting a rigid-MN, rather than a testable-MN, always useful in our search for

truth? { Among scholars who carefully study MN, most agree that

we should

ask "Is

it scientifically useful?" instead of relying on dogmatic rules. } {note: In

a longer version, before condensing, the Strong Man Contest is introduced as

a story about

a competition

I saw on ESPN. }

Will it be

scientifically productive? ( Is it a science-stopper?

)

Perhaps the search by Closed Science (restricted

by a rigid methodological naturalism) is occasionally

futile, like trying to explain how the faces on Mt Rushmore were produced by

undirected natural processes such as erosion. If scientists are restricted

by an assumption that is wrong (that does not correspond with historical reality)

the finest creativity and logic will fail to find the true origin of the faces.

Occasionally, perhaps MN is forcing

scientists into a futile search, like a man who is diligently looking for missing

keys in the kitchen when the keys are sitting on a table on the front porch. No

matter how hard he searches the kitchen, he won't find the keys because they

aren't there! On the other hand, if the keys really are in the kitchen,

they probably will be found by someone who believes "the keys are in the

kitchen" and is diligently searching there, not by a skeptic.

Perseverance and Flexibility: How

is scientific productivity affected by attitude? In the complex blend that

generates productive thinking, "There can be a tension

between contrasting virtues, such as persevering by tenacious hard work, or flexibly

deciding to explore new theories that may be more productive in a search for

truth. A problem solver may need to dig deeper, so perseverance is needed; but

sometimes the key to a solution is to dig in a new location, and flexibility

will pay off." {from Productive

Thinking: Creative and Critical}

Should scientists dig deeper in the

same location, or dig in a new location? Should they search the kitchen

or porch? The answer is YES if we notice that

one word is wrong, if we replace "or" with "and" because

we refuse to remain trapped in narrow thinking. Instead of thinking that

we must

make an either-or choice, we should search both kitchen and porch, we

should

dig deeper and in new locations, and this is allowed in open science. We

can

adopt

a

humble attitude "by refusing to decide that we already

know with certainty...

what kind of world we live in."

One night you find a man searching

under a streetlight. You ask why, and he says "I'm

looking for my keys." You ask, "Did they fall out of your pocket?" "Yes,

I was riding my bike when I heard them hit the ground a half-block up the

street." "Then why are you searching here?" "It's

easier

to search here because there is more light." / Here are two

questions to consider: Why

is

this

a joke? (is he

behaving rationally?) If he rigidly continues his limited search, will

he

find

the

lost

keys?

note: In

a page asking "Can

a design theory be scientific?", this

section

continues

by

asking "Is a claim for design a science-stopper?"

Here are some drama-stories I

invented in 2006 (along with introductions, etc, to provide a context) that

are in a "read me first" introduction-page for

an FAQ

about Creation,

Evolution, and Intelligent Design:

A Drama about People and Their Ideas

This website for Whole-Person Education is "a

resource for self-education, for busy people with ‘too much to do and

not enough time.’ We know you don't want to waste valuable time — because

as Ben Franklin said, "it's the stuff life is made of" — so

our goal is to help you learn a lot in a little time. (from the website-homepage)" The

website includes this FAQ — with responses to Frequently Asked Questions

about Creation, Evolution, and Intelligent Design — that is a condensed

summary of important ideas, designed to help you quickly get a "big picture" overview

of the ideas and their relationships.

In three decisions and a library I

recognized that this educational approach — giving you a quick overview

in a condensed summary — is analogous to Cliffs Notes that summarize and

analyze a fictional drama. In this FAQ you'll see the raw material

for an exciting non-fiction drama of real people and their ideas. The

drama is produced by encounters between people with contrasting ideas. These

ideas are often held with a confident passion by individuals and groups who often

behave as if they think people with other views are enemies who must be fought

and conquered. And the ideas have important implications and applications,

especially in education.

The summaries in this FAQ will help you quickly learn the

ideas in the drama. There is a sprinkling of illustrative examples (especially

in the eight full-length pages) plus conflict in four dramatic

contexts (in this page) but these are just "extra spice" to

supplement the main goal, which is to help you understand the real-life drama

of people and their ideas.

LATER IN THE PAGE,

2A. Warfare between science

and religion! This colorful portrait of history — with inherent

conflict causing rational science to be opposed by ignorant religion — is

dramatic (with heroes and villains clearly defined) and entertaining. It

is useful for anti-Christian rhetoric, and this was the main motive of its

most prominent popularizers. Even though a "conflict" perspective

is oversimplistic, inaccurate, and is rejected by modern historians, it has

exerted a powerful influence on popular views, and many people mistakenly think

irreconcilable conflict cannot be avoided.

Why? Some atheists (and rigid agnostics) want to believe

in "conflict" to support their personal rejection of Christian faith; some

Christians think statements in the Bible cannot be reconciled with conclusions

in science; and some people are confused by a scientism that goes

far beyond science, as in thinking that science shows miracles in the

Bible couldn't occur, or that when science explains how "it happened by

natural process" this shows "it happened without God."

2A is a pivotal section, since the next 16 sections (from 2B through 5G) are a response to show why science and Christian religion can peacefully coexist, despite the claims for "conflict" made by some atheists (against Christianity) and some Christians (against science).

Drama you can Imagine

Earlier, I describe the "exciting

drama of real people and their ideas." You can get a feeling

for this drama by using your imagination to visualize the conflicts in four situations

where we often see drama; one is below, and three are later, when we look

at evolution & design and education. These

stories illustrate conflicts — internal and external, within people and

between people — that commonly occur in real life. Imagine that:

• your pastor confidently declares, "the Bible

says the earth is young, so you should believe it." But your teacher

for Sunday School, who is a close friend and expert geologist, explains why science

shows the earth is old, and Genesis does not teach a young earth. You're

not a scientist and neither is your pastor, but when you ask him about this he

loans you a book by young-earth scientists, and their arguments seem to make

sense. Your pastor wonders if he should let your friend teach in his church,

and you have questions.

We'll look at these questions in Sections 2, 3, and 4.

AND STILL LATER, as an introduction for Sections 5, 6, and 7:

Our focus now shifts from WHEN to

HOW. You can get a feeling for the drama of "people and their

ideas (in Sections 5-7)" by imagining that:

• you're a flexible agnostic,

uncertain about God but willing to search for truth. You hear Richard

Dawkins declare that evolution did happen, so God isn't necessary, and smart

people don't believe in God. But another respected scientist explains

why evolution (astronomical and biological) is possible only because the

universe was intelligently designed with the detailed fine-tuning that is

necessary for life. And another explains how evidence for "intelligent

design" is evidence against a totally natural evolution. You're

confused, wondering whether Intelligent Design claims that evolution did

or didn't occur. And is design scientific? Some scientists claim

that design (but which one?) is scientific, while others claim it's religious

and it has no basis in science. These scientists disagree, but all

of their arguments seem logical, so you're baffled, wondering "what

is science" and "what is (probably) true" and "what

should we teach" and you have questions.

Applications in Education

The questions in Sections 1-7 often produce uncertainties

and conflicts within a person. But when we make decisions about education,

internal personal questions can become external interpersonal tensions,

and conflicts become visible and vocal. To get a feeling for the drama

of people and their ideas, imagine that:

• you're a science teacher

in a private Christian school, and last year several parents didn't like

what you said about the "when and how" of creation, about the evidence

for an old earth with an evolutionary history. They removed their children

from your school and began a campaign in local churches, encouraging other

parents to also boycott your school. Now your principal is blaming

you for the school's damaged reputation and financial problems, and is saying "if

you want to keep your job, you will change the way you teach science."

• you're a public school

teacher who is wondering what to teach about origins: Is there any

scientifically justifiable controversy about the "how" of origins? If

you think "maybe there is" and you explain why in class, will you

get in trouble with school administrators who fear the threat of an expensive

lawsuit? But if you don't, will you get in trouble with parents? What

is the best way to survive and thrive in the current climate of controversy?

• you are the friend of

a student who is a Christian, who has been taught by her parents (and by

her pastor and the teachers in his church-run school, which is the only school

she ever attended) that the earth is 6000 years old, and that evolution is

scientifically proposterous and is an evil idea invented by atheists who

hate God. She is very smart, has excelled in learning science and is

enthusiastic about it, and will soon enter college. / How

do you think she will respond — and what will happen with her interest

in science, her views about creation, and the quality of her faith — in

each of these situations: A) she attends a private college that

teaches the same ideas as in her K-12 school, but then she leaves this safe

haven for a graduate school (or medical school) where conventional old-earth

science is assumed; B) she goes to a public college where her

first science teacher is an aggressive atheist who ridicules Christians and

tries to destroy their faith; C) in her public college most of

the science teachers (for conventional astronomy, geology, and biology, plus

chemistry and physics) just "teach the science" with no apparent

worldview bias; D) same as C, but her geology teacher is a devout

Christian who hosts a Bible study in his home for college students, and is

a respected elder at her new church in the college town; E) she

attends a private college where the teachers, who are all devout Christians,

think there is no conflict between their faith and the old-earth science

they teach, and are sensitive and thoughtful in their interactions with students

who have other views.

The homepage for Origins Questions begins with the first four stories (but not the student) followed by this:

We'll help you explore your questions.

Yes, this is a fascinating

area, with hot debates about tough questions in science and theology. We

want to help you explore and learn. We'll begin with simple explanations,

and then if you want more depth we'll help you dig more deeply. ... { In the

whole page this

is followed by a description of the area for Origins Questions. }