Science

in Christian Perspective

Science

in Christian Perspective Science

in Christian Perspective

Science

in Christian Perspective

The Rev.

Dr. William H. Dallinger F.R.S.:

Early Advocate of Theistic Evolution

and Foe of Spontaneous Generation

J. W. Haas, Jr.*

Gordon College

haasj@mediaone.net

Wenham, MA 01984

From: Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith 52 (June 2000): 107-117.

William Dallinger (1839-1909) emerged from the dockyards of Devenport, Plymouth, to become a prominent British Methodist preacher, educator, and microbiologist. His childhood interest in microscopy led to a lifelong involvement in the study of microorganisms and the "brass and glass" of microscopy as well as to an important role in the British debate of the 1870s and early 1880s over spontaneous generation. In the tradition of John Wesley, he promoted science education in his denomination and to the general public through his leadership in the Wesley Scientific Society and his lectures for the Gilchrist Educational Foundation.

Ironically, his opposition to spontaneous generation placed him in the camp of John Tyndall, T. H. Huxley, William Carpenter, and other leading scientists who encouraged his work and smoothed his path into the highest levels of British scientific culture. In this paper, I outline Dallinger's life and accomplishments and examine the religious climate from which he developed his theistic evolution and experimental efforts to support Darwin. While many of his contemporaries saw life arising full blown, by a creative act, Dallinger saw a divine potter working with clay.

The Early Years

William Dallinger's rise to prominence from obscure roots was not uncommon in a time when ambition, hard work, and the right opportunity could overcome background. Raised in a staunchly Calvinistic Anglican home in the thriving naval and military district of Plymouth, he had the chance to explore his interests in the physical sciences under the approving eyes of his tutors, and hone artistic skills working in the shop of his father--an artist, printer, and copperplate engraver.1 Dissatisfied with the rigors of the family's Calvinism, he moved to an Arminian position in his early teens. Later, he was attracted to Methodism upon reading one of John Wesley's science-illustrated sermons discovered while browsing in a Plymouth bookstall.2 Joining in the work of a local chapel, he was groomed by the Rev. John McKenny for the Methodist ministry.3 Poor health discouraged him from pursing his first career choice--medicine.

In the fall of 1860, he headed for a year of study at McKenny's alma mater, the Training Institution in the London suburb of Richmond. The course of instruction featured a demanding curriculum that included Hebrew--the entire book of Psalms for the best prepared--English grammar, geography, history, arithmetic, some Greek and Latin, plus moral and natural philosophy with experiments on mechanics, hydrostatics and hydraulics, pneumatics, acoustics, and heat.4 His instructors included Thomas Jackson and William F. Moulton, future denominational leaders who would encourage his later duel career as scientist and cleric.

Life on the Circuit

The newly coined preacher's first ministerial appointment was in Faversham, Kent (1861-1863), an impoverished circuit subsidized by the Conference. He next spent a year at the Woolwich circuit of the London District (1864) followed by a move to the Bristol District (1865-1868). There he completed his five-year probationary period, and was admitted into "full connexion" with the Conference (1866). He was then able to marry Emma J. Goldsmith (1842- 1910), daughter of David Goldsmith of Bury St. Edmunds. Emma, as the sole heir of deceased wealthy parents, brought financial stability to the family, which later enabled her husband to purchase scientific apparatus, travel to scientific meetings, and assume the expensive social obligations of scientific societies.5 Their only child, Percy Gough, was born in the next year. Soon after, the young preacher was struck down with a severe case of consumption (tuberculosis) that forced him to withdraw from the active ministry for eighteen months.6 During this period, his childhood interest in microscopy was rekindled, and he took the first steps to develop a research program that would propel him into the elite of English science.

Upon his recovery from consumption, Dallinger was assigned to the Liverpool District (1868-1880), serving a diverse range of circuits in this Methodist stronghold. From 1874 to 1876, he preached at the 250-seat Great Crosby Chapel, seeking to reach an upper-middle class community. During this demanding period of his scientific activity, chapel membership increased from 143 to 171.

The Woolton Chapel built in 1866 was his last circuit assignment (1877-1880).7 John Farnsworth, prominent merchant and Mayor of Liverpool, paid for half the edifice. The members, mostly very wealthy and prominent in Liverpool society, insisted that the Church of England liturgy be used for worship. Membership was seldom more than thirty, yet the church supported its own minister. Dallinger's social contacts were expanded and his tastes for art and literature matured in this upper-middle class environment. Once again, chapel membership increased during Dallinger's tenure despite his intense extra-curricular science activity.

One Methodist biographer, commenting on his work in Liverpool, noted that Dallinger "faithfully discharged the duties of a circuit minister, leaving behind him affectionate memories among all classes of our people."8 In 1880 he was elected a member of the "Legal Hundred," Wesleyan Methodism's corporate entity--notably, the same year that he was elected fellow of the Royal Society. The boy from the dockyard had moved a long distance from his roots.

The Porcupine, a satirical review about Liverpool's social and political scene, offered an outsider's view of one of his 1870 sermons at the Pitt Street Church. From it we can gather something of his manner. The article says:

He is unlike any Methodist preacher in distancing himself from the stereotype of preaching style and behaviour characteristic of the circuit preacher. The opposite of the typical Englishman in personal appearance, he exhibits modes of thought and habits of reflection which are strange to the Briton ... there is in his physiognomy much of the Germanic ... with perhaps a tinge of the Norman, though he speaks and acts with more of the manner that is acquired in an English education. In the pulpit he fixes the attention of all his observers more by his singularity than by his charm. His voice is tolerably clear, but not powerful for, from time to time, his bodily strength gives way and he speaks with evident difficulty, which is sometimes almost painful. His choice of words is large, his taste in figure and metaphor is well-formed and well considered; nothing that he says is likely to offend the taste of the fastidious ... there is little chance of his outwearing the patience of a congregation by the paucity of his ideas in comparison with the multiplicity of his words.9

A Life-Changing Illness

As noted above, shortly after his assignment to Bristol (1865), Dallinger suffered a severe attack of consumption, the scourge of many young Englishmen. The recuperation process emphasized the Victorian prescription to spend as much time outdoors as possible. Dallinger took the opportunity to study German, the biblical languages, and the new German critical studies of the Bible.

As his health improved, he purchased a

quality microscope and learned the techniques involved in the use of the best

1/25" and 1/50" high-power objective available. (See Fig. 1.)

Initially, his interests were focused on the optical aspects of the microscope--objectives,

eyepieces, and condensers--and on microscopic technique. These concerns,

coupled with a keen interest in developing improved instruments and

understanding the theory of microscopy, were long-term features of his

scientific career that were instrumental in his selection as editor of the 1891

and 1901 editions of William Carpenter's popular book, The Microscope and

its Revelations.

microscopy, were long-term features of his

scientific career that were instrumental in his selection as editor of the 1891

and 1901 editions of William Carpenter's popular book, The Microscope and

its Revelations.

Forging a View of God, Humanity, and Nature

The enforced period of leisure from pastoral duties in Bristol afforded Dallinger an opportunity to consider how the new science as well as critical studies of the Bible related to his Christian faith. While he never describes the sources that influenced his thought, a key motivational factor was the high value John Wesley (1703-1791) placed on science.10 It appears that Dallinger developed his basic views on science and religion during 1865-1868, as he took up the study of optics and, subsequently, began his investigation of spontaneous generation.

Wesley maintained a lifelong interest in natural philosophy, seeking to bring "popular education" in natural philosophy to his people, and encourage his preachers to be conversant with major scientific themes.11

Wesley's published sermons often used topics from the natural sciences to illustrate and complement biblical topics. His use of natural knowledge went beyond traditional displays of the "wisdom of God," even beyond a heraldic link to a religious concept found with contemporary evangelicals, such as James Hervey and John Newton, and their nineteenth-century counterparts. While he occasionally allowed himself a moral gloss, Wesley emphasized his desire not to account for natural phenomena but to describe them--especially the unusual.12

At the same time, Wesley was aware that the science represented by the British enlightenment could have serious implications for traditional interpretations of the Bible and of the place ascribed to God in the functioning of the natural world. His peace with science would be occasionally broken when he encountered a raw materialism that viewed nature as operating independent of God as exemplified in his "13 Dallinger adopted Wesley's emphasis on the importance of science and of science education for clergy and laity, and his more-or-less consistent "live and let live" attitude toward new discoveries.

In examining Dallinger, I feel it important to view him as he wished to be seen--as a scientific amateur and a cleric. In the course of his later life, however, he preferred to separate his roles as a preacher of the Gospel and defender of the faith from his scientific life. Still, he followed in Wesley's footsteps in proclaiming the moral value of the study of the natural world. He notes:

Thus the ultimate demand of thought, of reason, and of consciousness, is when we are unraveling the modes of phenomena, pushing our inquiries into the conditions of all existences, generalizing vast areas of knowledge, expressing in formula of geometry and numbers the splendid rhythm and order of things in heaven and earth, we are simply finding, and expressing, the thoughts of an Infinite Intelligence; discovering the modes by which His immutable perfections were caused to take form in matter and mind.14

Enter Evolution

The period proceeding Dallinger's development of his core views on science and Christianity witnessed an intense discussion about the implications scientific discoveries in geology and biology had upon the interpretation of the Bible, and even about understanding natural theology within the broader Christian community. Religious reaction to theories of the earth's history and natural selection was diverse and often controversial; so too, has been the understanding of Methodist participation.15 Our sources are the works of Methodist authors and the discussion of science in Wesleyan periodicals, primarily the Wesleyan Methodist Magazine (WMM), the Youth Instructor (YI), the Methodist Recorder (MR), and the London Quarterly Review (LQR). Denominational periodicals offer windows of what is considered appropriate for the faithful to believe and what a community finds unacceptable.

Mark Clement's analysis of the period 1815-1870 illustrates the difficulty of assuming a commonality of views on science and religion even by a single group such as the Wesleyan Methodists. As Methodism expanded from Wesley's day, it attracted a diverse social constituency and, in moving from a sect to a denomination, underwent splintering into a number of groups from the original Wesleyan Methodists. Here we focus upon earth history and evolution, topics germane to Dallinger's interests.

There was little, if any, public

Methodist support of Darwin

during this early period.

Historically, geological issues preceded biological discussion. Wesleyan theologians, ministers, and laypeople of various backgrounds avidly discussed information emerging from the current investigations of earth history. There were clear implications for the age of the earth and the dimensions of the biblical flood. As evidence for an "old earth" accumulated, various schemes to accommodate the Genesis account were offered.16 Until 1830 the WMM was open to several different approaches toward harmonizing the biblical and geological accounts. Sequential creation at various times over long intervals (interval theory) was seen as a reasonable alternative to the notion of a "once for all" event 6,000 years in the past. About 1830, however, various writers, including leading Wesleyan theologian Richard Watson, dug in their heels against this violation of the scriptural account, concluding that mainstream geology was opposed to Genesis.17

The next fifteen years saw major resistance to all attempts at promoting reconciliation. Methodist publications were essentially silent on the subject. As late as 1847, the WMM would suggest that the study of geology had not as yet matured to the point for "a definite, uniform system" to be accepted. However, by the 1850s the WMM was willing to support a series of serial creations carried out between vast intervals of time and that the configuration of the crust of the earth--the rock strata and fossils--did not arise over a period of six literal, twenty-four hour days.18 Clement argues that by 1858 Wesleyan leaders had not only assimilated the concept of episodic creations but had begun to "comprehend the expansion of natural law to include the history of the inorganic, and, to a limited extent the organic worlds."19 The move from "being to becoming" was--however reluctantly--on.

E. Brooks Holifield found Methodists initially indifferent to Charles Darwin's Origin of Species (1859).20 Thomas Yorthy, on the other hand, found a much more contentious situation with the new science viewed as "intellectually linked to the philosophical heresies of the day.21 Traditional Christian understandings of creation and human nature were threatened. So, too, was any theology that took seriously the notions of perfection, the fall, the need for a Savior, baptism, supernatural destiny, and the argument from design. The all-devouring theory of evolution would not be satisfied until consciousness, thought, and moral facilities were reduced to physical laws.22

We may assume that Dallinger, a literate Methodist of means, would have subscribed to the major Wesleyan periodicals, especially the WMM and LQR. What could he have gathered about Darwin from the articles on the subject appearing in denominational literature? One cannot escape the fact that there was little, if any, public Methodist support of Darwin during this early period.

One key Methodist distinctive--the freedom to choose (or not to choose) the precepts of Christian faith--was seen to be a sticking point by those who saw Darwinism as a threat to moral agency. The danger came from the specter of a fixed inexorable law determining the moral decisions of persons. These critics sought to defend the moral potential of humankind against the perceived threat of Darwinism. Holifield suggests a link with eighteenth-century concerns to defend the freedom of the will against the Calvinists. However, there were important differences. He notes: "Wesley feared that Calvin had slandered the benevolent mercy of God, Victorian Methodists feared that Darwin defamed the moral character of man."23 Yorthy argues, however, that this theme was less important than the effect on the design argument and on intellectual links to the heresies of the day.

Clement suggests that the publication, Essays and Reviews (1860), an influential and controversial discussion of biblical higher criticism, was a complicating feature in the response to Darwin. Essays sought to separate the truth of Christianity from the literal historic truth of Scripture--bypassing the efforts of the scriptural geologists.24 At the same time, the foremost exponents of Darwinism (some became friends of Dallinger) were leading the new British push to professionalism in science with the goal of dissociating metaphysical and theological interests from the practice of science. This blatant attempt to separate science from religion by the new spokesman for science could not fail to repel the faithful.25 Dallinger followed the line of the biblical critics in arguing against the use of early Genesis as a scientific account of creation. On balance, however, the 1860s saw little Methodist support for Darwin or higher criticism.

In the face of this negativism,

Dallinger enthusiastically

adopted Darwinism--

though with reservations.

In the face of this negativism, Dallinger enthusiastically adopted Darwinism--though with reservations--joining the fellowship of those very individuals who sought to separate religion from science. We have no hint of the evidence that convinced Dallinger to endorse Darwin's theory. It is telling that while he felt that the origin of human life and life itself were direct acts of God, yet he was willing to examine evidence which suggested otherwise. Another decade passed (1877) before he openly offered his views to fellow Methodists, and a further decade before he gave full expression to them in his 1887 Fernley lecture. Over the years, he showed unusual restraint as one on the cutting edge of science who saw his partners in faith disparage the science that he saw as opening a different picture of design and God's providence. Dallinger, the man of science, felt that the evidence of science should not be subverted by a literal reading of Scripture. He developed an interpretation of Scripture that allowed him to affirm a nuanced theistic form of evolution, which he felt countered the threats to Christianity as seen by his peers. Over the next quarter century, many of his Methodist colleagues would join him.

Evidence for Spontaneous Generation Examined

What would distinguish Dallinger from most amateurs was the seriousness with which he approached his studies: first, in gaining a thorough knowledge of the most advanced microscopes of the time; then, to creatively use the tool in original scientific research. At Bristol, Dallinger spent his last year in part-time circuit ministry while, in his spare time, applying his newly-gained, microscopy skills to a study of some organisms alleged to cause "putrefaction" in organic bodies.26 Encouraged by the success of these private investigations, he sought to enter the public arena of science. His success was facilitated by his transfer to the Liverpool district in 1868.

The thriving city of Liverpool offered a number of cultural organizations where biological interests were pursued. These included the Philomatic Society founded in 1825, the Liverpool Literary and Philosophic Society (LLPS) founded in 1842, and the newly-founded Liverpool Microscopical Society (LMS). Before venturing into the national arena, Dallinger became active in these organizations, trying out his scientific ideas on local audiences. He was able to cultivate friendships with members, and gain credibility by the quality of his initial scientific studies and the strength of his comments during the discussion periods. His wife's inheritance provided the means to pay membership dues and cover the not inconsiderable costs of socializing with the leading figures of the city.

By the time he moved to Liverpool, Dallinger had a clear idea of the initial direction of his microbiological research program--one, I feel, motivated by a religiously-inspired view of the origin of life, and staunchly supportive of Darwin. His research over the next dozen years on monad life-cycles, spontaneous generation, and acquired characteristics was seen by many Wesleyan Methodists as excellent science and as supporting Christian principles, though the latter was not always clearly understood or appreciated.

The Monthly Microscopical Journal (MMJ) became a clearing house for the increasing number of reports on spontaneous generation found in the journals and scientific societies of England and North America, rising to a fever pitch in the early 1870s. The MMJ served amateur natural historians and professionals, who were concerned with improving the microscope and applying it to various fields. Contemporary British contributors in the discussion of spontaneous generation (or abiogenesis) on the national level included Lionel Beale, Gilbert W. Child, T. H. Huxley, John Tyndall, J. C. Dalton, and Henry C. Bastian.

Bastian, London University Professor of Pathological Anatomy, sparked the British debate with a bombastic, three-part defense of spontaneous generation, starting in the June 30, 1870 issue of Nature.27 He dismissed the investigations of Louis Pasteur: "People have been so blinded by his skill and precision as a mere experimenter, that only too many have failed to discover his shortcoming as a reasoner."28 In the July 7, 1870 issue, an irritated John Tyndall wrote: "It is much to be desired that some really competent person in England should rescue the public mind from the confusion now prevalent regarding this question."29 Dallinger took up the torch!

Bastian produced numerous papers and books showing alleged examples of the phenomena and relating the link between abiogenesis and evolution. Influenced by Ernst Haeckel, he would fight a tenacious but losing battle through the 1870s and 1880s. Later he suffered the embarrassment of having the Royal Society refuse to publish his findings.30 For the most part, Darwin and Huxley publicly stood above the fray. Leading scientist and evolution proponent John Tyndall, while committed to an original event, would be considered to have provided the definitive evidence against current occurrences by demonstrating that claimed instances were due to contamination, even though he worked solely with bacteria. James Strick has shown the pivotal role that the X club played in leading the battle against spontaneous generation--a battle spurred on, in part, by the desire to distance evolution from the origin-of-life question.31

Through the 1870s, advocates and critics of abiogenesis hotly debated the issues in varied venues ranging from local microscopy groups to the Royal Society. Dallinger would play a prominent role through his experimental work, popular articles, and lectures on the subject to a wide range of audiences.

By the time he arrived in Liverpool (1868), Dallinger had already developed the skills to follow the life-cycles of monads, microscopic organisms capable of study through then recent developments in microscopy. Bastian and others saw these organisms as exemplifying an easy transition from inorganic matter. To do the required, tedious, time- consuming, microscopic observations, Dallinger needed a co-worker--someone who had scientific standing plus the funds to pay part of the project expenses, and who shared his religious views. He found his man in Dr. John James Drysdale (1817- 1892), a well-to-do physician and leader in Liverpool scientific societies, who was an acquaintance of Huxley and Tyndall.32

The core of their research was presented in a well-received series of papers to the MMJ (1873-1876). The fatal flaw in all previous studies on bacteria and monads was a lack of information about the life-cycles of the various forms alleged to be de novo productions. Concerning a cercomonad obtained from maceration of a cod's head, they were able to observe a complex repeatable cycle involving in turn fission, fusion, and the production of infinitesimal spores that developed to the original mature forms.33 These relatively long-lived intermediates in the cycle could be mistaken for new unique forms by the unwary. Carefully drawn plates illustrating the various monad life-cycles accompanied the article, and were characteristic of Dallinger's attention to detail and artistic skill.

The duo spelled each other at the

microscope over the long hours required to gain life histories of entities that  challenged the microscope's limit of resolution. (See Fig. 2.) A bed was set

up nearby so that one of them could sleep while the other kept his eye glued to

the scene in the eyepiece. On occasion Emma would bring meals to them. They were

conservative in reporting their results, repeating observations until each had

seen every facet of monad behavior. Such obscure observers from the provinces

could not afford to make mistakes. Their papers drew the attention of the

leading scientists, including Charles Darwin, Huxley, Tyndall, William

Carpenter, Joseph Hooker, and William Parker, who saw to it that their work was

discussed in the leading scientific journals.34

challenged the microscope's limit of resolution. (See Fig. 2.) A bed was set

up nearby so that one of them could sleep while the other kept his eye glued to

the scene in the eyepiece. On occasion Emma would bring meals to them. They were

conservative in reporting their results, repeating observations until each had

seen every facet of monad behavior. Such obscure observers from the provinces

could not afford to make mistakes. Their papers drew the attention of the

leading scientists, including Charles Darwin, Huxley, Tyndall, William

Carpenter, Joseph Hooker, and William Parker, who saw to it that their work was

discussed in the leading scientific journals.34

Dallinger and Drysdale amicably parted ways when, at the close of the series, the latter wished to be involved in a survey of the Mersey estuary. Dallinger produced several experimental papers on bacteria over the next several years, and became a leading spokesman on the subject of spontaneous generation. His establishment friends smoothed his way into London scientific culture, seeing to it that his papers were published and nominating him to be a fellow of the Royal Microscopical Society, the Linneanian Society, and the Royal Society in 1880.

In support of Darwin

Shortly before his move to Sheffield (1880) to be Headmaster at Wesley College, Dallinger began preliminary experiments for what became a seven-year study on the question of whether it was possible to "superinduce" adaptive changes on life-forms whose life-cycle was relatively short. He wished to provide further evidence for Darwin's law of "concurrent adaptation to concurrent changes of environment." Not unexpectedly, he chose monads as the object of his study with temperature as the significant variable. He noted that Darwin had "shown great interest and given me great encouragement."35

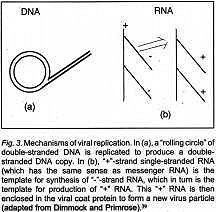

Dallinger selected a monad whose life-cycle averaged four minutes (360 generations/day). Even with this rate of turnover, several months were required to affect the ability of a monad to survive increasing temperature. His experimental skills and perseverance were tested to the extreme by the requirement that the entire system needed to be under a twenty-four hour, controlled thermal environment for an expected 500,000 generations. The constant temperature apparatus maintained the temperature to within +/- 0.25ƒ F. (See Fig. 3.)

Dallinger began his research at 60ƒ F.

and slowly raised the temperature over a period of four months to 73ƒ F. At

this temperature, many monads died or were not as productive. He maintained the

system at this temperature for three months, until the monads recovered their

former activity (adapted to a higher temperature). The temperature was again

raised in small increments until activity diminished; then they were allowed to

rest for a month to adapt to the change. This process was repeated over many

years until the last generation of monads "appeared as jolly as

sand-boys" at the temperature of 158ƒ F. at which point the apparatus was

accidentally destroyed. Interestingly, the higher temperature resistant forms

"perished directly when placed back in their ancestral medium of 65ƒ

F."36 The project had been stimulated by an

earlier remark by Darwin that the "lowest and least visible organisms could

be used to demonstrate the manner in which living creatures adapt to changed

circumstances and produce what are called new species."37

Dallinger's work demonstrated what

today would be dubbed "microevolution." A modern "natural"

example of this involved the development of shorter legs over a fifteen-year

period by lizards placed in an environment with much smaller trees than those in

their ancestral home.38 Dallinger's automated apparatus

required little attention, a necessity for the busy life of a school

administrator and frequent traveler to London as president of the Royal

Microscopical Society. However, his many absences caught up to him when his

apparatus failed after almost seven years of continuous operation (1877). The

Daily Telegraph lauded his efforts as having a "valuable bearing on the

problem of evolution" and his work as "an example of the admirable and

unceasing devotion of our scientific men."39 The American Monthly Microscopical

Journal said "no one can read his account without admiration for such

painstaking and experimentation ... such work done by our leaders inspires the

rank and file to work such as this which has given us scientific discoveries and

their benefit."40 Despite many ringing affirmations,

Dallinger did not return to the field that produced his scientific reputation.

Dallinger began his research at 60ƒ F.

and slowly raised the temperature over a period of four months to 73ƒ F. At

this temperature, many monads died or were not as productive. He maintained the

system at this temperature for three months, until the monads recovered their

former activity (adapted to a higher temperature). The temperature was again

raised in small increments until activity diminished; then they were allowed to

rest for a month to adapt to the change. This process was repeated over many

years until the last generation of monads "appeared as jolly as

sand-boys" at the temperature of 158ƒ F. at which point the apparatus was

accidentally destroyed. Interestingly, the higher temperature resistant forms

"perished directly when placed back in their ancestral medium of 65ƒ

F."36 The project had been stimulated by an

earlier remark by Darwin that the "lowest and least visible organisms could

be used to demonstrate the manner in which living creatures adapt to changed

circumstances and produce what are called new species."37

Dallinger's work demonstrated what

today would be dubbed "microevolution." A modern "natural"

example of this involved the development of shorter legs over a fifteen-year

period by lizards placed in an environment with much smaller trees than those in

their ancestral home.38 Dallinger's automated apparatus

required little attention, a necessity for the busy life of a school

administrator and frequent traveler to London as president of the Royal

Microscopical Society. However, his many absences caught up to him when his

apparatus failed after almost seven years of continuous operation (1877). The

Daily Telegraph lauded his efforts as having a "valuable bearing on the

problem of evolution" and his work as "an example of the admirable and

unceasing devotion of our scientific men."39 The American Monthly Microscopical

Journal said "no one can read his account without admiration for such

painstaking and experimentation ... such work done by our leaders inspires the

rank and file to work such as this which has given us scientific discoveries and

their benefit."40 Despite many ringing affirmations,

Dallinger did not return to the field that produced his scientific reputation.

The Fernley Lecture: Evolution Reluctantly Joined

Philantrophist James Fernley (1796-1874) had a strong interest in theology and Methodist intellectual life. He established the Fernley Lecture, which was an annual address on a theological theme given at the Wesleyan Methodist Conference. The leading lights of clerical Wesleyanism heard the lectures that were subsequently published and widely discussed in religious publications.

In 1880 Dallinger had been scheduled to deliver the annual Fernley Lecture on evolution and its effects on theism. Dr. George Osborn, several times president and influential conservative leader of the Conference, intervened and a hastily prepared substitute was found. Wesleyan theologian Henry J. Pope concurred with Osborn's action. He felt that evolution was probably true, but since it was still so controversial in Methodist circles, it would not be expedient to make it the subject of a Fernley lecture at that time.41 Dallinger's protege, Methodist cleric William Spiers, sought to calm a contentious situation by suggesting that one did not need to base one's destiny on a science that was constantly changing. He thought that it was just as easy to stay with the biblical creation story as with Dallinger's evolutionary explanation because the strong opposition to evolution on the part of scientists at that time (1882, the date of Darwin's death) could well see it die for want of sufficient evidence.42

By 1887 opposition to evolution had cooled and Dallinger was re-invited to address the Conference. His Fernley lecture, "The Creator and What We May Know of Creation," fine-tuned his "theistic evolution" to invoke the Creator at three points: the creation of matter, the origin of life, and the transition from ape to humans.43 The lecture was framed by the notion of self-acting laws of nature imprinted by the Creator.

Dallinger's exposition was offered in terms that would counter the concerns of an audience that even in the late 1880s included many with deep reservations about the implications drawn from evolution by William Spencer and others. While asserting his wholehearted acceptance of the Darwinian view, he sought to counter the arguments of those who used evolution to eliminate the Creator.

Dallinger sought to separate the roles of science and religion. "It is science alone that can discover and express the mode of action; it is theology alone that must strive reverently to lead the mind up from the mode, not to the conception, but to the inevitable existence and thought of the creator."44

He gently reminded his listeners that the Bible does not offer a scientific account or chronology of creation.

Creation by evolution or development is taking place forever around us ... development is evolution beginning at a fixed point; evolution is only development. Evolution is an integration of matter, and concomitant dissipation of motion, during which the matter passes from an indefinite, incoherent homogeneity to a definite, coherent heterogeneity, and during which the retained motion undergoes a parallel transformation.45

With soaring rhetoric, he enthused: "Can there be any splendor of the infinite mind more ineffable and effulgent than the evidence in His works, that in the beginning He determined the potency and perversion of all the life, and all the adaptations, that ever have emerged or can emerge?"46

While asserting his wholehearted

acceptance of the Darwinian view,

[Dallinger] sought to counter

the arguments of those

who used evolution

to eliminate the Creator.

Rather than denying design for these self-acting, self-adjusting systems, he argued:

It is only the design, the teleology of the old school touched by modern knowledge and changing into a conception of universal design that can have originated in an infinite mind ... the teleological and mechanical views of phenomena and their origin are not antagonistic, rather, they are the complement of each other.47

Citing his research on the adaptation of monads to changes in temperature, he noted: "In my judgement, the existence of the power of concurrent adaptation, possessed by every living organism in nature, is the broadest and sublimist evidence of design that can be brought before the mind of man."48

Responses to "The Creator and What We May Know of the Method of Creation" fell along the lines of how one viewed evolution. The Rev. Scott Liggett observed that "no one was a penny the worse!"49 The Primitive Methodist Magazine said that Dallinger had given an able defense of the doctrine that all things were made by God; a "valuable contribution in the battle against unbelief."50 His most serious critic (N.N.Y.) engaged him in several rounds of responses and rejoinders in the WMM.51 The most contended points were N.N.Y.'s charge that Dallinger placed God at the beginning and at the end of all things but not during the course of history, and that Dallinger's imposition of God at the origin of life and at the point of the origin of moral, reasoning humans was inconsistent with his notion of self-acting laws of nature.52 N.N.Y. also regarded the evidence for evolution to be insufficient.

His critic saw life arising,

full blown, by a creative act

while Dallinger saw

a divine potter working with clay.

Dallinger's detailed rejoinder found each point wanting either because his views were misread or not heard. He admitted that some things are "mysteries that can be explained only in the mind of God."53 Dallinger found N.N.Y. deficient in understanding the science of evolution--a response sure to inflame his critic's rhetoric.

The concluding exchanges saw each man holding his ground. As the debate lengthened, it became clear that N.N.Y. was adamantly opposed to any form of evolution. He challenged the value of Dallinger's adaptation experiments of the 1880s with a quotation from S. H. Parkes' Unfinished Worlds:

What, then, it may be asked is the lesson that these [Dallinger's] important experiments clearly teach? Certainly not the evolution of new species, but rather the extraordinary persistence of specific forms and their power of gradual adaptation to the very extreme conditions to which their long line of ancestors had been subjected54

One contentious exchange with N.N.Y. stemmed from Dallinger's endorsement of Huxley's line from his 1870 BAAS Presidential Address:

If it were given to me to look beyond the abyss of geological recorded time to the still more remote period when the earth was passing physical and chemical conditions which it can no more see again ... I should expect to see the evolution of living protoplasm from not living matter55.

Dallinger's emphatic, "so should I" created confusion in the mind of the critic who thought the statement countered Dallinger's dictum that life could not stem from the nonliving. The Methodists who lauded his spontaneous generation research had missed his point as well. Dallinger speculated (as Huxley) that life had emerged from non-life at some point in the past under unique conditions that were not naturally present in 1887. His research on monad life-cycles had thrown doubt on claims that spontaneous generation was a contemporary event.

In suggesting the possibility of the primordial event, Dallinger asks:

... being a witness of the origin of such living protoplasm from non-living matter, does it mean that I ignore the power needed to transform it? Does it mean that such transformation by method-law is unworthy of the creative power?56

His critic saw life arising, full blown, by a creative act while Dallinger saw a divine potter working with clay. The London Quarterly Review felt that the issue was not whether God created via an evolutionary process but whether there was sufficient evidence to prove it. N.N.Y. was confident that the evidence would not be forthcoming.57

An Active Life

While best known for his contributions to microbiology and evolutionary thought, Dallinger served his church and the scientific community in many ways. From 1861-1880, he ministered to circuits, rich and poor, from Favorsham, Kent, to the Wolton Chapel in Liverpool. He was Governor at Wesley College, Sheffield, from 1880-1887. From there, he moved to Lewisham, a suburb of London, where he lived until his death in 1909.

Dallinger gave more than 450 popular science lectures under the Gilchrist Educational Trust to large audiences throughout England."58

A description of one lecture held at the Exhibition Building in York survives.

The listener [H. G. S. Wright] sat transfixed as the tall spare man, clean shaven save for a fringe of beard under the chin, held forth with almost inspired eloquence on the aqueous marvels revealed by the lens. He came away determined to save his pence for a microscope; he was later to become a world authority on the sessile rotifers.59

Dallinger was the founding father of the Wesley Scientific Society (1887-1891) and the Wesleyan Naturalist.60As author from 1877-1899 of the Wesleyan Methodist Magazine "Science Notes," he was the scientist to Methodists. Dallinger's organizational skills served him in many years of service to the Royal Microscopy Society (President, 1883-1887) and to the Quekett Microscopical Club (President, 1891-1893). He was the founding president of the Glasgow Microscopical Society. He gave a spring series of popular lectures on microscopy at the Royal Institution in the years 1878, 1884, and 1888.61 Recognition of his contributions to science came in the form of honorary doctorates; the LL. D from Victoria College, Toronto, in 1884, the D. Sc. from Dublin in 1892, and the D.L.C. from Durham in 1896.

Conclusions

Dallinger played an important role in helping British Methodists adapt to the scientific culture following Darwin's Origin. Earning the right to be a scientific insider, he sought to support Darwin's ideas from a theistic perspective, which saw God's unceasing action in creation. He says:

Design, purpose, intention, appear when all the facts of the universe are studied ... teleology does not now depend for its existence on Paleyean "instance"; but all the universe, its whole progress in time and space, is one majestic evidence of teleology.62

Dallinger, as Wesley, was willing to give science its due. He was, however, a stickler for evidence. His own work demonstrated many cases where evidence offered for spontaneous generation in the 1870s and 1880s was faulty. Yet, he repeatedly stated that he would accept de novo examples, if supported by clear evidence. He was even willing to link humans with "the great progressive chain of living forms that had peopled the earth through countless ages," but felt that "the gulf between man and the noblest apes is such as to be practically without comparison."63

Eclectic evangelical professor at the Free Church College, Glasgow, Henry Drummond, associated for a time with evangelist Dwight L. Moody, supported an all-encompassing evolutionary process grafting an evolutionary sociology and ethics upon a biological frame.64 Dallinger strongly opposed any form of social Darwinism arguing that "nature is non-moral," and that "religion begins with Christ."W. Robertson Nicoll, "65

©2000

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Martha Crain, research librarian of Gordon College, Mary Nixon of the Royal Society Library, and the staffs at the Local Studies Centres at Bury St. Edmunds, Sheffield, and Lewisham, UK, for help in finding sources. Jim Moore and James Strick have offered helpful observations and encouragement.

Notes

1A baptismal certificate lists his birth as July 5, 1839. Census records and other sources list his year of birth as 1840, 1841, or 1842. The article "Science and Christianity, an interview with the Rev. W. H. Dallinger," The Quiver (1889): 351-5 was the basis for the biography in Dictionary of Standard Biography and the obituaries in Nature 82 (November 18, 1809): 71-2 and Proceedings of the Royal Society Series B 82 (1910): iv-vi. William Spiers, "Dr. Dallinger's Life Work," Wesleyan Methodist Magazine (hereafter WMM) (1910): 46-50 is an appreciative account by a cleric-naturalist friend. A biographical sketch was published recently: J. W. Haas, Jr., "The Reverend Dr. William Henry Dallinger, F.R.S. (1839-1909)" Notes and Records of the Royal Society (January 2000): 53-65.

2M. Simpson, "W. H. Dallinger," Cyclopedia of Methodism, 4th rev. ed. (Philadelphia: Louis J. Everts, 1885), 274.

3Dallinger offered an emotional testimony on McKenny's role in his conversion at the reading of McKenny's obituary at the London Circuit meeting 1903; "Obituary Notice for William H. Dallinger," in Minutes of Several Conversations at the One Hundred and Sixty-seventh Yearly Conference of the People Called Methodists (London: The Epworth Press, 1910), 135.

4Frank E. Cumbers, ed., The Richmond College, 1843-1943 (London: The Epworth Press, 1944), 131.

5See will of David Goldsmith, 1860 in Bury St. Edmunds, Suffolk, Record Office. Local History Archives file J599/1.

6The Quiver (1889): 351-2.

7Frank Gordob, For All that is past: St. James Methodist Church, Woolton (London:The Epworth Press, 1966).

8"Obituary Notice," WMM 133 (1910): 135.

9The Porcupine (12 March 1870): 484.

10J. W. Haas, Jr., "John Wesley's Views on Science and Christianity: An Examination of the Charge of Antiscience," Church History 63 (1994): 378-91. Dallinger quoted Wesley in support of the mission of the Wesley Scientific Society. See the Wesley Naturalist 1 (1887): 2; Ibid. 2 (1888): 1.

11See J. W. Haas, Jr., "John Wesley's Vision of Science in the Service of Christ," Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith 47 (1995): 238-43.

12John Wesley, "Remarks on Buffon's Natural History," in The Works of John Wesley, XIV vols. (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1958), 452.

13Remarks on the Count De Buffon's Natural History" (1782). He railed at Buffon's advocacy of spontaneous generation, regarding it "utterly inconsistent with reason and scripture." Ibid., 452-3, 454-5.

14W. H. Dallinger, The Creator, and What We May Know of the Method of Creation (London: Charles H. Kelly, 1887), 51.

15See Mark Clement, Sifting Science: Methodism and Natural Knowledge in Britain 1815-1860 (master's thesis, Wadham College, University of Oxford, 1996); E. Brooks Holifield, "The English Methodist Response to Darwin," Methodist History 10 (1972): 14-22; Thomas Yorthy, "The English Methodist Response to Darwin Reconsidered," Methodist History 32 (1994): 116-25. My account of the period 1840-1860 follows the line of Clement.

16Clement, Sifting Science, 60-6.

17Richard Watson, Theological Institutes (New York: Carlton and Lanahan, 1850).

18Ibid., 83.

19Ibid., 85.

20Holifield, "The English Methodist Response to Darwin," 14.

21"Yorthy, "The English Methodist Response to Darwin Reconsidered," 120.

22Ibid.

23Holifield, "The English Methodist Response to Darwin," 21-2.

24Clement, Sifting Science, 137-40.

25Frank Turner, "The Victorian Conflict between Science and Religion: A Professional Dimension," Isis 69 (1973): 372.

26It appears that Dallinger's initial research was in response to the new work of E. Haeckel, Generelle Morphologie der Organismen, 2 vols. (Berlin: G. Reimer, 1866).

27See James Strick, "Darwinism and the Origin of Life: The Role of H. C. Bastian in British Spontaneous Generation Debates, 1868-1873," Journal of the History of Biology 32 (1999): 1-42.

28H. C. Bastian, "Facts and reasonings concerning the heterogeneous evolution of living things," Nature 2 (1870): 170-7; 193-201; 219-28.

29H. C. Bastian, "Facts and reasonings concerning the heterogeneous evolution of living things," Nature 2 (1870): 170-7; 193-201; 219-28.

30He finally privately published his work as H. C. Bastian, The Origin of Life: Being an account of experiments with certain superheated saline solutions in hermetically sealed vessels (London: Watt & Co., 1911). James Strick vividly describes the role of X Club members in opposing Bastian; Strick, "The British Spontaneous Generation: Debates of 1860-1880: Medicine, Evolution, and Laboratory Science in the Victorian Context" (Ph.D. diss., Princeton University, 1997), 150-7, 287-92 and Strick, "Darwinism and the Origin of Life."

31Strick, "Darwinism and the Origin of Life." See Ruth Barton, "Huxley, Lubbock, and Half a Dozen Others: Professionals and Gentlemen in the Formation of the X Club 1851-1864," Isis 89 (1998): 410-44 for a discussion of the early days of the club "devoted to science, pure and free, untrammeled by religious dogmas" (p. 411).

32Drysdale introduced Huxley at a dinner meeting of the LLPS in 1869 where he gave an impassioned plea for radical changes in English science education and argued that clerics should cultivate science. Thomas H. Huxley, "Science Education: notes on a after-dinner speech, Liverpool, 1869," in Science and Education (New York: P. F. Collier & Son, 1902), 101-19. He corresponded with Tyndall about his own Life and the Equivalence of Force (1870) and The Protoplasmic Theory of Life (1874). Drysdale also supported the project financially; Royal Society Government Grant Applications 1877-1883, vol. 1 (London: Royal Society, 1880), 22.

33W. H. Dallinger and J. Drysdale, "Researches on the Life History of a Cercomonad: A Lesson in Biogenesis," Monthly Microscopical Journal 10 (1873): 52-8.

34Beside the team's six publications in the Monthly Microscopical Journal (1873-1877), Dallinger published extensions of their work in Nature, Popular Science Review, Proceedings of the Royal Society, Popular Science Monthly, and Royal Institution Proceedings. Abstracts of the papers were printed in regional British journals and several American journals.

35William H. Dallinger, "President's Address," Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society 10 (1887): 191-2.

36Report of the "President's Address," Daily Telegraph (19 Feb. 1887): 5.

37Ibid., 5.

38See J. Losos, K. Warhut, and T. Schoener, "Adaptive differentiation following experimental island colonizing in Anolis lizards," Nature 387 (1997): 70-3; also T. Case, "Natural Selection Out on a Limb," Nature 387 (1997): 15-6.

39Report of the "President's Address," 5.

40W. H. Dallinger, "President's Address," published as "The Rev. Dr. Dallinger's Presidential Address," American Monthly Microscopical Journal VIII (1887): 114.

41J. Scott Leggett, "The Theological Institutions: Some Noted Tutors of Yesteryear," London Quarterly and Holborn Review 118 (1936): 10.

42William Spires, "Charles Robert Darwin," WMM 105 (1882): 488-94.

43Dallinger, "President's Address," 16.

44Ibid., 51.

45Ibid., 56.

46Ibid., 57.

47Ibid., 61-2.

48Ibid., 72.

49J. Scott Lidgett, "The Fernley Lecture," The London Quarterly Review 69 (1887-1888): 361.

50Review, "The Fernley Lecture," Primitive Methodist Magazine (1888): 57.

51The critic was identified only by his initials. N.N.Y.

52W. H. Dallinger, "Dr. Dallinger's Rejoinder," WMM 111 (1888): 394.

53 ------, "The Fernley Lecture, 1887. A Rejoinder," WMM 111 (1888): 135-44, 220-225.

54.------, "Dr. Dallinger's Rejoinder," 389.

55------, "The Fernley Lecture," WMM 110 (1887): 945.

56------, "The Fernley Lecture, 1887. A Rejoinder," 140.

57Lidgett, "The Fernley Lecture," 361.

58William Henry Dallinger," Proceedings of the Royal Society, B 82 (1910): iv.

59Herbert S. Henderson, "Presidential Address," Microscopy 33 (1979): 414.

60Herbert S. Henderson, "Presidential Address," Microscopy 33 (1979): 414.

61Frank Greenaway, ed., Royal Institution Archives: Managers Minutes 1874-1903 (London: Scholar Press 1971): XIII 142; XIV 119; XV 55.

62Dallinger, "The Fernley Lecture," 74.

63Ibid., 75.

64Henry Drummond, The Ascent of Man (New York: James Pott & Co., Publisher, 1900).

65Introduction I" in Henry Drummond, The Ideal Life (Cambridge, MA: University Press, 1913), 21.