Science

in Christian Perspective

Science

in Christian Perspective

Science

in Christian Perspective

Science

in Christian Perspective

From: Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith 50

(March 1998):32-40.

This article explores how the concepts of ecology are presented and utilized in the evangelical Protestant response to the ecological crisis. It finds that there are seven basic themes in the literature: (1) etymological discussions; (2) the concepts of interdependence and balance; (3) cycles and energy flow; (4) food chain/food web/ecological pyramid; (5) carrying capacity; (6) the idea that humans are the disrupters of "nature's" balance; and (7) the contrary idea that humans are a part of the ecosystem. In light of these themes, I make several observations. One is that the summarized findings of ecology becomes the latest version of natural theology: God's will is for each ecosystem to be a climax ecosystem which never declines. If this is the case, then western agriculture, industry, and the use of much technology will have to be severely curtailed--a situation unacceptable to most evangelical Protestants.

Many scholars have argued that western culture, infused with a Christian understanding of the world, provided a nurturing environment for the development of science. The belief in a purposeful God, the argument goes, who gave order and coherence to the universe allowed scientists to assume that they could discover such order, such "laws." God made a world which was consistent and real, and therefore predictable. The discipline of ecology has also benefited from Christian assumptions embedded in western culture. By the time ecology began to develop as a scientific discipline, however, these assumptions had become "secularized," or stripped of their God-talk. In other words, early ecologists did not have to believe in a Christian God to assume that the world was orderly, consistent, real, and predictable. These beliefs had become cultural norms taken for granted by everyone in the West; they could be understood by an ecologist as simply similarities between Christianity and science, rather than shared beliefs which have their "genesis" in Christian doctrine.

Not surprisingly, it is these assumptions that evangelical Protestants emphasize when informing their audience about the concept of ecology.1 Furthermore, probably in part because of these shared assumptions, the languages of ecology and theology are mixed together without any serious discussion about what the potential differences could be--not so much a synthesis as a bricolage. This article is an attempt to describe and analyze the concept of ecology contained in the evangelical Protestant response to the ecological crisis, and to raise questions about its use.

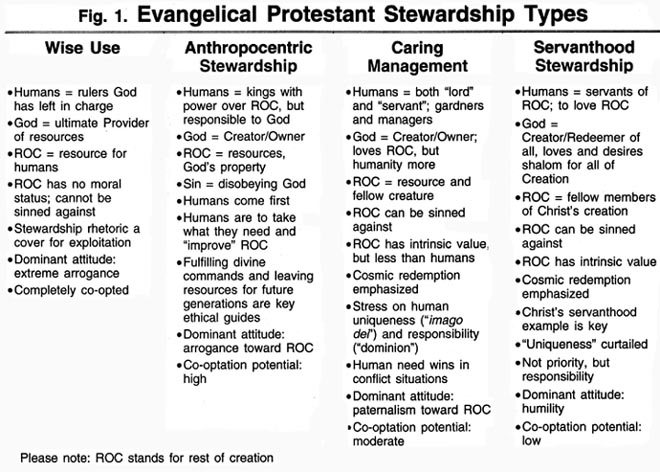

But before addressing this, a brief overview of the evangelical Protestant response to the ecological crisis is necessary. I have summarized the four main ways evangelical Protestants have utilized the concept of stewardship and have created a four-part stewardship typology (see Fig. 1). The capacity for the theological and ethical position of each type to be turned into a justification for exploitation of the rest of creation is what I call its co-optation potential. Rating each type in this way is obviously a judgment on my part. As such, I should declare that I have the greatest affinity with the fourth type, Servanthood Stewardship. The four stewardship types are as follows:

1. Wise Use: Happily, only a few evangelical Protestants fall into this type.2 The name comes not from Gifford Pinchot's utilitarian conservation ethic, which actually reflects the phrase, and is in keeping with my Anthropocentric Stewardship type. Rather, it comes from the co-opted version represented by former Reagan Interior Secretary James Watt, Ron Arnold of the Center for Defense of Free Enterprise, Alan M. Gottlieb, editor of The Wise Use Agenda, and Rush Limbaugh.3 This political "movement," bank-rolled by companies who would profit from deregulation, seeks to promote an open-throttle, all-out exploitation of the rest of creation (ROC).

The evangelical Protestants of the Wise Use type are providing a theological rationale for such exploitation. Wise Use does not include the evangelical Protestants who are opposed to any ethic of creation-care.4 Rather, those in this type seek to offer an alternative which actually works against caring for creation. God is indifferent

to the rest of creation, and thus it has no moral status. Moreover, the best strategy for achieving the welfare of present and future generations is not conservation but economic growth and "resource substitution." Thus, Wise Use's co-optation potential has been fully realized.

2. Anthropocentric Stewardship: This type, a legitimate ethical stance when compared to Wise Use, is widely held by evangelical Protestants.5 Persons who fall into this type stress that the rest of creation was created for the welfare of humanity. Some writers may mention briefly that God declared the rest of creation to be "good," a few even suggesting that it has some modicum of intrinsic value. But this is overwhelmed by talk of "resources" and a strong (and usually defensive) emphasis on the idea that humans come first. Theologically, the focus is on the divine-human relationship. Since the possibility of a moral status for the rest of creation is either denied or discounted severely by adherents of this type, its co-optation potential is high. Rhetorically, the only difference between Wise Use and Anthropocentric Stewardship is the argument that it would be better for future generations to conserve rather than exploit the rest of creation.

3. Caring Management: Many of the writings of the "major players" in the evangelical Protestant response to the ecological crisis belong in this type.6 There is a both/and quality to Caring Management. Humans are both "lord" and "servant" when it comes to the rest of creation, unique in the sense of being created in the image of God, but responsible for the care and management or "dominion" of the rest of creation. In many instances, the two Genesis texts (1:26-28 and 2:7,15) are balanced off each other, with the Golden Mean being what I describe as Caring Management. The rest of creation is both a resource for legitimate human needs and something which shares in our creaturehood and deserves our respect and care. Sometimes the tension within the both/and juxtaposition is so great as to be contradictory. Their rhetoric, i.e. the specific language they use and the way in which they structure their arguments, appears to be based upon an awareness of the writings of "environmentalists," and an awareness that many evangelical Protestants are characterized by the Wise Use and Anthropocentric Stewardship perspectives. In effect, they are saying to their fellow evangelical Protestants, "Look, some of what the environmentalists are saying is true. Trust us; we've listened to them critically and we've weeded out all the crazy stuff. But the biblical message is that we can't be anthropocentric. We've got to care for the rest of creation, too." Thus, due to its both/and nature, Caring Management's co-optation potential is moderate. Its most effective bulwarks against the erosion of its position are the espousal of the concepts of intrinsic value and cosmic redemption.

4. Servanthood Stewardship: While the majority of evangelical Protestant writings on the ecological crisis fall under the categories of Anthropocentric Stewardship and Caring Management, a strong and significant minority belong in the Servanthood Stewardship type.7 The Lord/servant tension of Caring Management is relaxed in the direction of servanthood. There is less of an emphasis on the Genesis texts when it comes to understanding humanity's role, and more of an emphasis upon emulating Christ in servanthood as described in Phil. 2:6-11. Following Christ in servanthood is the key to understanding a Christian's ethical attitude toward all creation. There is an avoidance of hierarchical thinking. A belief in cosmic redemption suggests that God loves and desires shalom for all creation. Thus, the stress is not on whether humans have priority but on their responsibility. Servanthood stewardship's co-optation potential is low due primarily to its attitude of humility, its espousal that God loves the rest of creation, and its resulting belief in intrinsic value and cosmic redemption.

Now that a brief overview of the evangelical Protestant literature on the ecological crisis has been given, a description and analysis of the literature's use of the concepts of ecology can proceed. In general, many of the writings do not define the concept of ecology or describe it in any great detail.8 When they do, the discussion is usually quite brief, and the overall effect is to paint a picture of stasis, that what is "natural" for "nature" is a static harmony.

There are seven basic themes in the literature concerning the concepts of ecology. First, some writings begin with an etymological discussion: the word ecology comes from the Greek word, oikos, meaning the family household and its order and maintenance; numerous commentators point out that the English words ecology and economy come from this common root.9 (Many writers tie in the idea of stewardship: a steward is one who manages the household, which in this instance encompasses both "nature" and the economy.10) Early on Barnette provided the best and most succinct definition in the evangelical Protestant literature: "Ecology is the study of the relationship of all living creatures to each other and to their environment."11

Second is the theme of the two interrelated overarching concepts of interdependence and balance, both of which serve as the theoretical core around which the other themes cluster. Concerning interdependence, the literature really does not go much farther than John Muir's oft quoted statement from My First Summer in the Sierra: "When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe."12 Indeed, in many instances the words of evangelical Protestants are- whether intentionally or not--a paraphrase of Muir. For example, Snyder states of the world that "everything within it is tied to everything else."13 It could also be the case that evangelical Protestants are picking up Muir's quotation from Barry Commoner, or from those who utilize his work. He takes Muir's quotation and makes it into his "First Law of Ecology: Everything is Connected to Everything Else."14 Indeed, evangelical Protestant Richard Young summarizes each of Commoner's four laws of ecology.15 Although many ecologists would not want to make such a sweeping "metaphysical" statement, (i.e. that everything is connected to everything else) evangelical Protestants writing on the ecological crisis are quite comfortable making this type of assertion because they share with Muir a belief that God in fact made the world this way: interdependent, everything related to everything else.16 The word "community" is often used. This type of relational holism is seen as consistent with the biblical (Hebraic) view of creation.

When it comes to the idea of balance, the underlying assumption is stasis; left undisturbed by humans, the rest of creation is a balanced harmony. The concept of balance is stressed because the anthropogenic ecological crisis is perceived to have created various imbalances. This attitude is summed up in the first proposed title by George Perkins Marsh for his classic, Man and Nature, "Man, the Disturber of Nature's Harmonies."17 If there is any sense of natural ecological change, it is teleological development: left to its own devices, each ecosystem will eventuate in a rich, stable, balanced fecundity and diversity of life.18

The third theme stresses the biochemical side of ecology: cycles and energy flow. Evangelical Protestants succinctly describe how energy from the sun is stored in plants which become food for animals, and how in this life-sustaining process of energy flow the Earth has various cycles, such as the carbon cycle, the hydraulic cycle, and the nitrogen cycle. Closely aligned to energy flow is the fourth theme, that of the food chain, food web, or ecological pyramid. Here, obviously, are specific ecological terms which reinforce the general concept of interdependence.

The idea that ecosystems have a carrying capacity, which means that there are limits beyond which ecosystems cannot be pushed without the possibility of collapse, is the fifth theme. Pollution, habitat destruction, species extinction, and many other anthropogenic disruptions, if not halted, will lead to the degradation and eventual collapse of the Earth's ecosystems.

The sixth and seventh themes, that humans are the disrupters of "nature's" balance and that humans are a part of the ecosystem, are in constant tension with each other. They highlight the fact that borrowing from the discipline of ecology has not answered one of the key theological questions underlying the ecological crisis: "What is humanity's relationship to the rest of creation?"

In light of these seven themes several comments are in order. First, the evangelical Protestant versions of the concepts of ecology which the literature has emphasized appear to put all of my stewardship types except Servanthood Stewardship on the defensive. This is ironic, considering that, according to Worster, a "bioeconomics paradigm" with a perspective quite in sympathy with Anthropocentric Stewardship began its reign in the field of ecology in the mid-forties, and is still widely followed today.19 As Worster points out, this bioeconomics perspective has a great deal in common with a "Progressive conservation philosophy" (e.g., Gifford Pinchot), wherein scientifically trained experts utilize the information obtained from the field of ecology to better manage the ecosystems of the Earth.20 When answering the question "What is humanity's relationship to the rest of creation?" both Anthropocentric Stewardship and Caring Management rely on the "both-a-part-of-and-apart-from" answer. The "bioeconomics paradigm" leans toward the more transcendent "apart-from" view of humanity. Yet the evangelical Protestant emphasis on interdependence, "community," and the literal stress on the idea that human beings are to be viewed as "a part of" the ecosystems they inhabit, obviously leans towards the immanent "a-part-of" understanding of humanity's relationship to the rest of creation. This means that Anthropocentric Stewardship and Caring Management proponents must counter this effect to create a more "balanced" answer to the question: "What is humanity's relationship to the rest of creation?" In many instances they do so theologically, by highlighting the concepts of imago dei and dominion.

The reason for this irony, I believe, and this need to counterbalance theologically the concepts of ecology evangelical Protestants highlight, is because they have been influenced more by the popularizers of ecology (e.g., Aldo Leopold, Rachel Carson, and Barry Commoner). These thinkers are more "organismic,"21 in their writings, more willing to create a holistic, ecological ethical philosophy from their understanding of the findings of ecology than the average scientist in the field of ecology itself.

A second observation concerns the overall impression of stasis created by the evangelical Protestant descriptions of the concepts of ecology. The themes of balance and cycles seem to diminish any sense of change or linear, temporal movement. This can feed into the dualistic separation of "nature" and "history" wherein the only significant changes occur in human culture--when in fact the rest of creation is constantly changing, moving into ecological successions and regressions without any help from humanity.

A third comment regards the fact that the concepts and summarized findings of ecology at times become the latest version of natural theology: the rest of creation reveals to us the character and intentions of God. God blessed all creation; God's will is for each ecosystem to be a rich, stable, balanced and harmonious diversity--a "climax" (Clements) or "mature" (E. Odum) ecosystem which never declines. This, of course, sounds more like the Garden of Eden than the findings of a scientific discipline. At times writers approach Muir's dualism. For Muir, wilderness (i.e., creation which had not been disrupted by human culture) was "unfallen, undepraved,"22 and therefore "perfectly clean and pure and full of divine lessons."23 In wilderness or undisturbed ecosystems, God's intentions and character can be much more easily seen when compared with fallen human culture.24 Many times in the evangelical Protestant literature, the invocation of the mantra "Nature knows best" appears to be leaning toward this humanity is fallen, rest-of-creation is unfallen dualism. In other words, an undisturbed climax ecosystem is an excellent picture of God's will for creation.25 If God's intentions are for each ecosystem to be arrested at the climax stage of succession, then western agriculture will have to be junked, as will most of the other activities of an industrial, technological society.26 None of the evangelical Protestants reviewed here would be in favor of this, nor would they want to be perceived as advocating some type of return to a romanticized version of hunter-gatherer societies. Furthermore, do evangelical Protestants really want to profess that the rest of creation is "unfallen," or that the "curse" has been completely lifted? Does the rest of creation need the healing of Christ's atoning death irrespective of human activity?

Finally, an obvious consideration not to be overlooked is the context within which evangelical Protestants write: the perception that there is a problem, a crisis. Since things appear to be out of "balance," or even out of control, then balance and limits must be stressed; and since humans appear to be the problem, then interdependence, community, and being a part of the ecosystem needs to be emphasized.

Notes