Science

in Christian Perspective

Science

in Christian Perspective Science

in Christian Perspective

Science

in Christian Perspective

Rationality in Science and

Theology:

Overcoming the Postmodern Dilemma

F. LeRon Shults

Bethel Theological Seminary

3949 Bethel Drive

St. Paul, MN 55112

From: PSCF 49 (December 1997): 238-236.

This paper examines the structures of rationality that underlie the way we as individuals think and act, whether in science or in theology. It attempts to show how our knowledge is shaped by a tension between absolutism and relativism, or what this author calls the "postmodern dilemma" (although it is an old dilemma in a new form). A taxonomy of "structures of rationality" is proposed, and correlated to three developmental stages. The fecundity of the final "relationalist" structure is illustrated in the critical realism of W. Van Huyssteen and the use of complementarity logic by W. Jim Neidhardt.

Those of us who are interested in relating scientific thinking and Christian faith, whether as scientists or theologians, find ourselves caught on the horns of a dilemma. On the one hand, it seems that recent work in the philosophy of science has demonstrated the provisional, contextual, and subjective nature of all knowledge, even in the "hard" sciences. This aspect of the "postmodern" critique suggests that it is impossible for us to know what is "real." On the other hand, as Christians who affirm the reality of God and the contingent reality of nature, we want to argue for a real objective world "out there" about which we can make truth-claims in science and theology. We are caught in a tension between relativism and absolutism.

Most of us carry on our professional lives without considering this dilemma; perhaps we even think the whole issue is somewhat superfluous. Nevertheless, whether we are aware of it or not, we all resolve the dilemma; but the resolution is at such a deep level that we are able to "know" without "thinking" about it. In fact, the way we think and act in our disciplines is powerfully shaped by the way we resolve this deep tension between viewing knowledge as absolute or as relative. Unfortunately, I believe Christians are too easily pulled, often unconsciously, toward resolving the tension by giving in to the relativism of our "postmodern" age, without recognizing the impact this will have on the way we do science and theology.

This paper suggests that the way a person resolves the dilemma of absolutism vs. relativism is shaped by his or her "order of consciousness," a phrase borrowed from Robert Kegan.1 By correlating this psychological description of stages with a description of what I will call "structures of rationality," we may gain a better understanding of one factor influencing our everyday thinking. One of the most important discoveries of this correlation will be that relativism is not necessarily the last word.

Our first task, however, must be to clarify briefly what we mean by "rationality." The classical model of rationality, which sought certain and self-evident foundations for knowledge, and clear rules to follow based on those foundations, has collapsed under the clamoring throng of the postmodern crowd. Harold Brown has shown that we will always need a reason for why we select the foundations we do (or how we know they are self-evident).2 The classical model of rule-following, foundationalist rationality always results in an infinite regress: searching for foundations for foundations. Brown proposes a new model that features "judgement" within a community. The details of his proposal3 are less important for our purposes than the fact that he takes "the notion of a rational agent as fundamental, and such notions as `rational belief' as derivative in the sense that a rational belief will be one that is arrived at by a rational agent."4 The move from making "rational" a predicate of a proposition or a community to applying it to individual agents is critically important for understanding the proposal of this article. It sets the stage for understanding how an individual's ability to think rationally is shaped by his or her underlying "order of consciousness."

Robert Kegan's "Orders of Consciousness"

My goal in this first section is to show how Robert Kegan's "subject-object" theory outlined in his 1994 book, In Over Our Heads, provides a developmental scheme that can help us explain the structures that underlie and shape rationality in both science and theology.5 In an earlier work, The Evolving Self, Kegan described the evolution of the self as it develops through a set of stages called "evolutionary truces." These are temporary solutions "to the lifelong tension between the yearnings for inclusion and distinctness."6 In his 1994 book, he expands his theory to clarify the central importance of the underlying structure of the relationship between subject and object within each stage.

Kegan speaks of five

"orders of consciousness," each evolving as a more complex way of

relating the subject (or the knower) to the object (or the known). This theory

grew out of his desire to elucidate the core structural commonalties underlying

the cognitive and interpersonal characteristics of the developmental stages. For

our purposes, the critical orders of consciousness are the third, fourth, and

fifth, which Kegan refers to as "traditionalism,"

"modernism" and "postmodernism," respectively. (In the next

section, we will propose a taxonomy of "structures of rationality"

that correspond to these three orders of consciousness). Let us review each

briefly, with reference to Chart 1.

The first thing to notice about the chart is that the contents of the "subject" box are moved into the "object" box with each new order of consciousness. So, for example, whereas in the second order, one constructs knowledge out of one's point of view (childhood), a person in the third order "backs up," so to say, and objectifies his or her own point of view, as one among others (typically in adolescence). The qualitative nature of this transformation obtains for each new underlying structure, including the move to "postmodernism."

Kegan illustrates the difference between the third and fourth orders of consciousness by describing a couple who are struggling with the issue of interpersonal intimacy in their marriage. He notes that if each spouse constructs the self at a different order of consciousness, each will have a different idea of what it means to be intimate, or to be near another "self." In the fourth order, the self becomes subject to its third order constructions "so that it no longer is its third order constructions but has themº [now] the sharing of values and ideals and beliefs will not by itself be experienced as the ultimate intimacy of the sharing of selves, of who we are."7

The move to the fourth order is a qualitative difference, involving more than just the inclusion of more complex content within the same mental frame. It requires a transformation of the third order, with its underlying cross-categorical structures, from whole to part, i.e., from subject to object. The move to a "systemic" (fourth) order is not something that can be taught like a new skill. It normally takes a long time for an individual to "negotiate" such a complete transformative change. Introducing new complex ideas to a person who still constructs the subject-object relationship in the third order will not by itself accomplish a transformation. Rather, the person will tend to fit the newer concepts into the old order and "make the best use it can of the new ideas on behalf of the old consciousness!"8 As we will see below, the same phenomenon occurs when a scientist or theologian attempts to accomodate new ideas; the underlying structure of knowing shapes the way the new concepts fit into his or her frame of reference.

Although Kegan focuses most of his case material on helping to understand movement up to the fourth order (which his research indicates most educated adults have not reached), he points out that culture is quickly moving to a point of demanding the fifth order. This is his interpretation of the emergence of "postmodernism" in various disciplines and cultural spheres. These new demands in so many arenas of life "all require an order of consciousness that is able to subordinate or relativize systemic knowing (the fourth order); they all require that we move systemic knowing from subject to object."9 This final "order" is important to understand, for I will argue that at this level a person gains a new capacity to overcome the postmodern dilemma, without collapsing into relativism or absolutism.

To understand the fifth order more clearly, it will be helpful to take an example that is particularly relevant to our topic: Kegan's discussion of "knowledge creation" from a fifth order of consciousness, and its relationship to "postmodernism." The move out of the fourth order means a relativizing of the "system" from its throne as subject, recognizing that all of its constructions are grounded in subjectivity. It is a process of "differentiating" the self from the fourth order of knowing. But then, asks Kegan, is post-modernism (being "beyond" the fourth order) also about a new kind of "integration" after the "differentiation," or is the creation of knowledge hopelessly ungrounded? Here he distinguishes between two kinds of postmodernism: deconstructive and reconstructive. Both point to the limits of knowledge, to the "unacknowledged ideological partiality" of every discipline and theory. For the deconstructivist this leads to the unacceptability of any position and the devaluation of commitment. The reconstructive approach, on the other hand, makes an "object" of the limits of our disciplines and theories:

for the purpose of nourishing the very process of reconstructing the disciplines and theoriesº When we teach the disciplines or their theories in this fashion, they become more than procedures for authorizing and validating knowledge. They become procedures about the reconstruction of their procedures. The disciplines become generative. They become truer to life.10

As a theory about theory-making and a stand-taking about the way we take stands, a reconstructive approach to postmodernism will necessarily make judgments concerning theories and stands that are not aware of the relativized mental structures that uphold them. The more complex order of consciousness is "privileged" only because it is "closer to a position that in fact protects us from dominating, ideological absolutes."11

In essence, the move to the fifth order of consciousness requires that one take the relationship itself as prior to its parts: "Do we take as prior the elements of a relationship (which then enter into relationship) or the relationship itself (which creates its elements)?"12 This primacy of relationality in the "fifth" order of consciousness will be a key to overcoming the postmodern dilemma through what I will call a "relationalist" structure of rationality.

Before moving on to a description of my taxonomy, it is important to emphasize that my appropriation of Kegan's "orders of consciousness" is qualified in at least three ways. First, the use of this model is not meant to suggest that psychology "explains" the experience of human knowing. It describes only one factor among many (historical, physiological, spiritual, etc.). Second, the model is not intended, even by Kegan, to be elitist. Having a numerically "higher" order does not make a "better" person, either morally or intellectually. The taxonomy merely describes increasing levels of complexity, which may lead to more competence in some areas. Third, my use of Kegan's model is not an attempt to "prove" a theological point by appealing to the authority of psychology. Rather, it is an attempt to outline a proposed correlation between two structural aspects of human knowing.

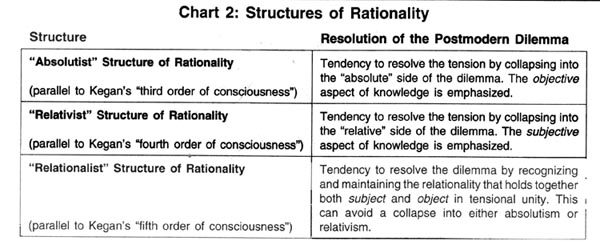

Structures of Rationality

By a "structure of rationality" I

mean the underlying tendency, within an individual, to lean toward one side or

the other (absolutism and relativism) in resolving the tension between the

objective and subjective aspects of knowing. In a sense, this

"structure" plays a mediating role between a person's "order of

consciousness" and the actual outworking of his or her theology or science.

The model I propose (see Chart 2 below) suggests that a transformation of one's

structure of rationality, analogous to that of a move from a fourth to a fifth

order of consciousness, strengthens one's capacity for "upholding" the

kind of resolution required to overcome the postmodern dilemma.

It is important to recognize that while there is a shaping relationship between orders of consciousness and an individual's structure of rationality, it is not a causal relationship. This schema of three structures is a measure of the way the self holds onto its constructions, and not a critique of the constructions themselves. The point is that individuals with absolutist or relativist structures may talk about potential resolutions of the dilemma like "critical realism" or "complementarity logic" (which we will examine later), but these concepts are put to use in the service of constructing a less complex order of consciousness, which weakens their ability to avoid a one-sided collapse of rationality. That is, their underlying frame of reference has not developed to match the explanatory constructs which are referents in the frame.

The "relationalist" structure offers the possibility of turning the postmodern dilemma "inside outº "

An individual with an "absolutist" structure of rationality will be more likely to try to resolve the dilemma on the side of absolutism. That is, he or she will continue to search for foundations in order to have a ground of certainty. The possibility that others have different foundations emerges with the third order of consciousness because one's "point of view" becomes object rather than subject in the knowing process. The "relativist" pull of the dilemma is generally repelled or ignored, although this rejection may be based on a variety of different foundations or absolutes, as we will see.

A person with a "relativist" structure of rationality, on the other hand, will resolve the tension by leaning toward the "relative" side of the dilemma. Here the relationship between various foundations, sets of rules, and communities of discourse (rather than one tradition or another) becomes the object of knowledge, but the relationality itself is not yet primary. Although Kegan's research indicates that less than half of all educated adults have achieved this "fourth" order of consciousness, it would seem that most theologians and scientists who are struggling with issues of rationality, epistemology, and interdisciplinary method, are at least at this level. We can see, for example, in Ian Barbour's description of "integration" and "dialogue" models for relating science and religion that these begin with the disciplines as separate, and then try to work out the relationship between them a posteriori, indicating a fourth order of consciousness.13 In the "modern" Cartesian era, when the task was one of being a detached observer of the "outside" world,14 such an approach may have seemed sufficient. In our "postmodern" era, however, attempts to resolve the dilemma of absolutism vs. relativism from a fourth order of consciousness will almost inevitably lean toward the side of relativism.

A "relationalist" structure of rationality, on the other hand, takes the tensional reality of subject and object in knowing as a relational unity that precedes the description of either side. We may think, for example, of Martin Buber's comment that it is in the "between" that spans subjectivity and objectivity that truth is found.15 By framing the situation in this way, this structure of rationality can recognize the contextual, provisional nature of the "subjective" side of knowledge, but simultaneously affirm the real (or true) existence of the "objective" side of knowledge. It is out of the relationality itself, out of the tensional unity of subject and object in the knowing event, that rational judgments are constructed.

By proposing a "relationalist" structure of rationality, I am not attempting to end discussion by sliding into a solipsism of subjective knowing (as the "traditionalist" might think), nor am I surreptitiously smuggling a new kind of absolutism into knowledge (as the "modernist" might think). Instead, the "relationalist" structure offers the possibility of turning the postmodern dilemma "inside out," i.e., of allowing the inherent relationality-in-tensional-unity of subject and object in the act of knowing to "order" our rational constructions. However, the fact that individuals may share a "relationalist" structure does not mean that all their theories will have the same content. On the contrary, individuals will attempt to resolve the dilemma in very different ways. There are a multitude of attempts to find a middle way, as Bill Placher puts it, between the extremes of universalism and radical relativism.16 However, the possibility of actually overcoming the dilemma, and not merely resolving the tension by leaning to one side or the other, is increased when a person reaches a fifth order of consciousness and achieves a "relationalist" structure of rationality.

Let us now examine each of these three structures of rationality in more detail by exploring some examples. All of the examples will be of scholars who have attempted interdisciplinary dialogue between theology and science, because it is in the context of such attempts that a person's underlying order of consciousness is most clearly revealed.

The "Absolutist" Structure of Rationality

We will spend the least amount of time on this structure because most scholars interested in the shaping of rationality as a common resource in theology and science have moved beyond it. Perhaps the clearest examples of constructions that appear to be formed by "absolutist" structures of rationality are found in the works of those who adhere to extreme forms of scientific materialism and biblical literalism. Although completely opposed in the content of their theories, these paradigms seem to be constructed out of remarkably similar orders of consciousness. As van Huyssteen points out, both are based on a foundationalist epistemology and share the following characteristics:

Both believe that there are serious conflicts between contemporary science and religious beliefs; both seek knowledge with a secure and incontrovertible foundation, and find this in either logic and sense data (science), or in an infallible scripture or self-authenticating revelation (theology); both claim that science and theology make rival claims about the same domain and one has to choose between them.17

In the terminology I have been developing, we would say that scientific materialists and biblical literalists are likely to have an "absolutist" structure of rationality that is shaped by a third order of consciousness. Underlying the constructions of individuals from either camp is a rationality shaped by the collapse of the postmodern dilemma toward the side of absolutism. Both commitments lead to an interdisciplinary approach limited to ex parte pronouncements, chipping away at the foundational pillars that support the opponent's epistemic temple. Even if an individual's rationality does not exhibit these extremes, a person with a third order of consciousness will at least lean toward the absolute or "objectivist" side of the dilemma. Clearly this structure of rationality is not up to overcoming the postmodern critique; it merely tends to ignore the contextual, fallible, non-exhaustive nature of human knowledge.

A fourth order of consciousness upholds and shapes rational constructions in a qualitatively different way. The cross-categorical structures of the third order of consciousness ("traditionalism") become object instead of subject of the knowing event (see Chart 1). This level of development is adequate for most scientific and theological work. It is only when the relational constructs introduced into our experience demand new modes of thinking that its limitations are revealed. Because this is the structure out of which most of us construct our knowledge, it will be critical to understand how it can shape our response to the postmodern dilemma. In this section, we will look at two concepts that are often found in attempts to explain the role of rationality in science and theology: critical realism and complementarity. I hope to show that a "relativist" structure of rationality may not be sufficient for successfully constructing these concepts as resolutions of the absolutism vs. relativism dilemma. In the next section, we will look at these two concepts as case studies again, but ask how a "relationalist" structure of rationality may be better suited to the task of upholding them.

Critical Realism. A well-known proponent of this approach in the science and theology dialogue is Arthur Peacocke. He notes that "critical realism" is a broad term with nuances of meaning, used differently by various authors. In his book, Theology for a Scientific Age, Peacocke explains: "critical realism recognizes that it is still only the aim of science to depict reality and that this allows for gradations in acceptance of the `truth' of scientific theories."18 He describes his epistemic approach as critical (not naive) because it acknowledges that our constructs are in the form of metaphoric language that cannot be taken literally. It is realist because it affirms that even our provisional language does actually refer to a reality beyond the knower.

Clearly Peacocke's use of critical realism is an explicit attempt to respond to the postmodern dilemma. How well does it work? The first clue that Peacocke may be operating with a "relativist" structure of rationality is found in the way he begins with the two poles or sides of knowing, the critical (representing subjectivity) and the realist (representing objectivity), and then tries to work out a possible resolution. This way of "ordering" the subject-object relationship shapes his rationality so that he tends toward relativism whenever a conflict emerges. When treating scientific issues, his view of knowledge seems more realist than critical; but on theological topics his approach is more critical than realist. This waffling between two separate epistemic convictions is symptomatic of an underlying structure of rationality that starts by holding the sides of the postmodern dilemma apart.

Statements about God are relativized, and judged in accordance with the reigning scientific paradigm (which, Peacocke admits, is itself relative). For example, only after explaining in scientific terms "how God might interact with the world," argues Peacocke, can we "with integrity assert that God does, or might do so."19 This would seem absurd applied to the personal knowledge of a friend or spouse: "I cannot assert that I know or relate to my wife until after I understand and explain how it is scientifically possible for communication between two human minds." Even the title of his book is revealing: theology is for a scientific age, rather than simply in it. Our goal, he says over and over, must be to revise traditional doctrines so that theology can be "credible" to scientists.20 Here we can see the effects of a fourth order of consciousness: in actual practice, it collapses theological rationality into relativism. Peacocke approaches knowledge with an initial vision of two distinct sides, and then tries to formulate the possibility of a relationship, indicating a "relativist" structure of rationality.21

Complementarity. Niels Bohr also addressed the relationship of subject and object using the language of complementarity:

In order to describe our mental activity, we require, on the one hand, an objectively given content to be juxtaposed to a perceiving subject, while, on the other hand, no sharp separation between object and subject can be maintained, since the perceiving subject also belongs to our mental content.22

Bohr realized that this complementarity of subject-self and object-self was the prior condition necessary for us to have conscious constructs at all. I am arguing that underlying what Bohr refers to as the relationship between "the conscious content and the background we loosely term ourselves"23 is an order of consciousness that upholds the relationship between them. I believe that Bohr's application of complementarity logic to the relationship of subject and object, along with his insistence on the irreducible role of the observer in all knowing, points to an exciting possiblity for overcoming the postmodern dilemma.

A problem may arise, however, if the concept of "complementarity" is used in the context of a "relativist" structure of rationality. One such example may be K. Helmut Reich's argument that the Chalcedonian formulation (two natures, without confusion, without change, etc.) is an example of complementarity thinking. Setting aside the content of Reich's solution for now, it seems that he has constructed his solution out of a "relativist" structure of rationality. He begins by framing the problem in terms of logically conflicting statements.24 By beginning with the "poles" of Christ's humanity and his divinity, and then trying to explain the relationship, Reich appears to be constructing the relationship out of a "fourth" order of consciousness. He does not see the relational unity of the person of Jesus Christ as hermeneutically prior to the two natures. Nor does he include the role of the council members (or of the contemporary believer), as observer/worshippers in relation to the experienced reality of Jesus Christ, in his application of complementarity. Yet, it is the insistence on including the relational role of the knower in the description of the knowing event that provides the power behind the concept of complementarity.

Reich also exhibits a "relativist" structure of rationality when he describes "thinking in terms of complementarity" in ways that lean almost exclusively toward the subjective side of knowing. For example, in an article on religious education, he refers to young people who are able to maintain two conflicting statements, as in the case of religious vs. scientific accounts of the origin of the universe, as thinking in terms of complementarity.25 However, simply holding two conflicting statements simultaneously is not the same as "complementarity" in the complex sense in which it emerged with Niels Bohr (involving asymmetry, coinherence, coexhaustiveness, etc.). The reasoning capacities of the children and adolescents tested by Reich illustrate a kind of thinking that requires nothing more than blind paradox, which can be constructed as content by a third order of consciousness (typical of adolescents in Kegan's scale). Reich's use of complementarity fails to overcome the postmodern dilemma because his structure of rationality leads him to collapse the tension toward subjective constructivism, which leans toward relativism.

The "Relationalist" Structure of Rationality

To illustrate the "relationalist" structure of rationality, we will explore two additional attempts to resolve the postmodern dilemma: the critical realism of W. van Huyssteen and the use of complementarity logic by W. Jim Neidhardt. It is important to remember that we are dealing with a shaping, and not a causal, relationship. On the one hand, a person with a fifth order of consciousness may construct his or her knowledge in a way that leans toward absolutism or toward relativism. On the other hand, a person with an "absolutist" or a "relativist" structure of rationality may embrace the content of critical realism, complementarity, or some other conceptual resolution of the postmodern dilemma. In the latter case, however, such constructs would be inherently unstable, as we saw with Peacocke and Reich, because the underlying order of consciousness is insufficiently complex to support the resolution. There are clues in the writings of van Huyssteen and Neidhardt, however, that suggest a fifth order of consciousness underlying and shaping their rationality.

Critical Realism. Like Peacocke, van Huyssteen proposes a critical realist epistemology that is explicitly designed to overcome what I have called the postmodern dilemma. Arguing for a position between what he calls "literalism" and "fictionalism," van Huyssteen defends a view of knowledge that takes seriously, but not literally, the idea that our partial, provisional language does refer in an "ontological or cognitive sense."26 He suggests that we retrieve critical realism as a "fallibilist, experiential epistemology" to help us construct a "post-foundationalist" model of theistic belief, which avoids the absolutism of foundationalism and the relativism of anti-foundationalism.27 How is this different from Peacocke?

First, van Huyssteen starts by affirming "the relational character of our being in the worldº the fiduciary rootedness of all rationality."28 The adjective "experiential" in his epistemology indicates that his terminus a quo is the relationality of subject-object in the knowing event. This suggests an order of consciousness that does not assume a bifurcation of knower and known and then try to explain how they relate. Rather, van Huyssteen argues that the essential post-foundationalist move entails an interactionist or "relational model of rationality" that recognizes concepts and theories as "products of an interaction in which both nature and ourselves play a part."29 He does not start with "critical" on one side and "realism" on the other, and try to force them together (as Peacocke does). Instead, he takes that kind of systemic knowing as object rather than subject, constructing his resolution out of the relational unity of a "relationalist" structure of rationality.

Complementarity. Like Helmut Reich, W. Jim Neidhardt was a trained physicist who turned later in life to the science/theology discussion. He too became specifically interested in the possible heuristic analogy between the hypostatic union in the Chalcedonian formulation and the complementarity interpretation of wave/particle duality in quantum theory. As I argued above, any attempt to apply complementarity logic should take into account the role of the rational agent, and be based in a "relationalist" structure of relationality. I believe Neidhardt's approach fulfills these criteria.

First, regarding the role of the knower, Neidhardt follows the post-critical philosophy of Michael Polanyi, and argues for the "participatory" nature of all knowledge, whether theological or scientific.30 For example, unlike Reich, Neidhardt sees the Chalcedonian fathers as starting with the relational unity of Jesus Christ as truly God and truly human. They included their own roles as knowers and worshippers in their description of the knowledge of the One who can only be known completely and truly through participating in his inner life with the Father by the Spirit. As he explains in The Knight's Move: The Relational Logic of the Spirit in Theology and Science, a work co-authored by theologian James Loder, this is not trying to force two opposites together, but the attempt of "participating" knowers to carry out the most rigorous effort reason could make, which in this case was structurally compatible with the complex inner logic of complementarity.31 Neidhardt starts with the hypostatic union as the indissoluble unity between God and humanity in Jesus Christ, and then argues that this relationality "constitutes the ontological ground for claiming that relationship is definitive of reality."32

Neidhardt also speaks of a figure-ground reversal between relationality and its polarities, so that relationality is viewed as fundamental. In terms of the subject-object relationship, he argues that "the intelligible order of reality is not in the mind, as Kant thought, or in nature, as Newton thought, but it resides in the relationship between mind and nature, the observer and observed."33 Concerning the postmodern dilemma, he offers a resolution, using the terminology of Kierkegaard, that does not collapse into either side, but maintains the tensional unity: "only through deeply indwelt particularity is universality able to be known and appropriated."34

In relating science and theology, Neidhardt explicitly rejects starting with the disciplines as separated and trying to "integrate" them. Instead, he begins with a "fundamental epistemology"35 in both fields that consists of "reciprocal asymmetric relations between two poles, the reciprocal relations between the poles maintaining a unitary structure that represents the complex unity intrinsic to the object and the representation of the object as the object shows forth to us."36 These clues from his work indicate that Neidhardt's attempts to overcome the postmodern dilemma are upheld by a fifth order of consciousness. Because his epistemological resolution is analogically related to a central resource of the Christian faith (the logic of Chalcedon), Neidhardt provides an excellent example of the influence a "relationalist" structure of rationality may have on the interdisciplinary dialogue between science and theology.

Conclusion: Implications for Interdisciplinary Method

The blurring of boundaries between disciplines in our "postmodern" world has made the task of relating science and theology significantly more complex.37 Is it possible that the development of a "relationalist" structure of rationality, as a resource shared by both scientists and theologians, may help to heal some of the epistemic wounds of the infamous "warfare" of the past few centuries? It is critical that we attempt such a move because, as I have argued elsewhere,38 we are in a situation worse today than that described by C.P. Snow several decades ago when the "two cultures" of the arts and sciences could no longer communicate. We now have dozens of "cultures" (disciplines) that cannot communicate, with the threat of further fragmentation from relativists who would argue that each one of us constructs our own culture.

The ASA has contributed greatly to the healing of this fragmentation by encouraging exploration of the relationship of science and Christian faith. In this paper, I have tried to suggest that these efforts may be undergirded by a deeper examination of the underlying structures of rationality which shape the way we as scientists and theologians hold onto our beliefs and practices. A "relationalist" structure of rationality may propel us to move beyond "integrative" or "dialogue" models of interdisciplinarity. It may require a recognition of the relationality between us as prior to either "conflict" (confligere) or "consonance" (consonare). Instead, we may think of interdisciplinary method as a "conquest," or a seeking-together (conquirere) after the intelligibility of creation. Such an approach would include the goal of helping one another, as individuals, develop structures of rationality truly capable of overcoming the postmodern dilemma.

©1997

Notes

1Robert Kegan, In Over Our Heads: The Mental Demands of Modern Life (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994).

2Harold Brown, Rationality (New York: Routledge, 1990).

3For a critique, cf. A.A. Van Niekerk, "To follow a rule or to rule what should follow? Rationality and judgement in the human sciences" in J. Mouton and D. Joubert (eds.), Knowledge and Method in the Human Sciences (1990): 179ñ94. Pretoria: HSRC.

4Harold Brown, Rationality, 185.

5Kegan, In Over Our Heads: The Mental Demands of Modern Life.

6óóó, The Evolving Self: Problem and Process in Human Development (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982), 108.

7óóó, In Over Our Heads: The Mental Demands of Modern Life, 114.

8Ibid., 97.

9Ibid., 316.

10Ibid., 330.

11Ibid., 333.

12Ibid., 313.

13Ian Barbour, Religion in an Age of Science (San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1990).

14Cf. Stephen Toulmin, The Return to Cosmology: Postmodern Science and the Theology of Nature (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982), 237.

15Cf. John W. Murphy, Postmodern Social Analysis and Criticism (New York: Greenwood Press, 1989), 21.

16William C. Placher, Unapologetic Theology: A Christian Voice in a Pluralistic Conversation (Louisville, KY: John Knox Press, 1989), 13.

17Wentzel Van Huyssteen, The Shaping of Rationality in Science and Religion. Paper presented at the Religion and Science Conference of the Royal Institute of Philosophy, University of Warwick, UK (March 1995): 4.

18Arthur Peacocke, Theology for a Scientific Age (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1993), 12.

19Ibid., 150.

20Ibid., 335.

21Cf. Arthur Peacocke, "From DNA to DEAN" Zygon 26, no. 4 (1991): 490.

22Quoted in Abraham Pais, Niels Bohrs Times: In Physics, Philosophy and Polity (Oxford: Clarendon, 1991), 440.

23Niels Bohr, Atomic Physics and the Description of Nature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1961), 100.

24K. Helmut Reich, "The Chalcedonian Definition: An Example of the Difficulties and the Usefulness of Thinking in Terms of Complementarity" in Journal of Psychology and Theology 18, no. 2 (1990): 153.

25K. Helmut Reich, "Between Religion and Science: Complementarity in the Religious Thinking of Young People" British Journal of Religious Education 11 (spring 1989): 68.

26Wentzel Van Huyssteen, Theology and the Justification of Faith, trans. H. F. Snijders (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1989), 157.

27óóó, "Critical Realism and God: Can there be Faith after Foundationalism?" In A. van Niekerk, et. al., (Ed.), Intellektueel in Konteks Opstell vir Hennie Rossouw (1993): 254.

28Ibid., 257, emphases mine.

29Van Huyssteen, The Shaping of Rationality in Science and Religion, 29.

30W. Jim Neidhardt, "The Participatory Nature of Modern Science and Judaic-Christian Theism," Journal of the American Scientific Affiliation 36, no. 2 (1984): 98.

31James Loder and W. Jim Neidhardt, The Knight's Move: The Relational Logic of the Spirit in Theology and Science (Colorado Springs: Helmers and Howard, 1992), 85.

32Ibid., 200.

33Ibid., 43.

34Ibid., 104.

35Cf. Lee Wyatt and W. Jim Neidhardt, "Judeo-Christian Theology and Natural Science: Analogies An Agenda for Future Research" Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith 43, no. 1 (1991): 14ñ28 and F. LeRon Shults, "A Theology of Chaos: An Experiment in Postmodern Theological Science," Scottish Journal of Theology 45, no. 2 (1992): 223ñ36.

36W. Jim Neidhardt, "The Creative Dialogue Between Human Intelligibility and Reality: Relational Aspects of Natural Science and Theology" The Asbury Theological Journal 41, no. 2 (1986): 60.

37Cf. Raphael Sassower, Knowledge Without Expertise (New York: State University of New York Press, 1993) and G.J. Roussow, "Theology in a Postmodern Culture: Ten Challenges" in Hervormde Teologiese Studies 49, no. 4 (1993): 894ñ907.

38F. LeRon Shults, "Integrative Epistemology and the Search for Meaning," Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies 5, no. 1 (1993): 125ñ40.