Comparative Analysis of the Nuclear Weapons Debate: Campus and Developer Perspectives

JACK C. SWEARENGEN ALAN P. SWEARENGEN

Office of the Secretary of Defense Church of the Savior

Strategy, Arms Control & Compliance Servant Leadership School

The Pentagon 1640 Columbia Rd., N.W.

Washington, DC 20301 Washington, DC 20009

Many statistics (e.g. numbers, tonnage, killing capacity) regarding nuclear weapons and their effects are available to both sides of the weapons debate, including weapon designers and anti-nuclear activists. However, the same statistics are frequently used to support very different conclusions. The process is shaped by the convictions of each sector because the convictions determine how information is obtained, interpreted, distributed, and used by a sector's members. In this paper we have considered the debate over nuclear weapons from perspectives taken by designer and campus activist. We look at the questions usually raised by each community, the common forms of communication used, and the role of objectivity in each. U.S. nuclear weapons policy and apparent underlying assumptions are outlined, and opposing viewpoints are discussed. We have concluded that the perceived power of the members of each community to influence issues tends to determine how information is used. In time, the associated information becomes more important than the weapon itself. For Christian members of these opposing communities, we set forth some biblical perspectives that are independent of particular convictions about weapons.

From: PSCF 42 (June 1990): 75-85.

Preface

Since this writing in early 1989, a number of amazing events have occurred which

have portents for U.S. defense posture. A popular demonstration for democracy in

the Peoples Republic of China was crushed in Tiananmen Square; the Berlin wall

has been opened; the USSR has begun withdrawing conventional forces from eastern

Europe; Warsaw Pact countries are undergoing such major political changes that

the existence of the Pact as a military alliance is questionable; Soviet Foreign

Minister Shevardnadze admitted that the Krasnoyarsk Radar site was indeed in

violation of the ABM Treaty; and the B-2 Stealth bomber made a successful maiden

flight.

The opposing communities on both sides of the U.S. defense debate are responding

predictably. For example, "arms controllers" interpret Shevardnadze's admission as a good faith

demonstration of genuine change and

that the Soviet State is becoming more benign. Calls have been issued for

reductions in the U.S. defense budget, possibly by as much as one-half within a

decade. Strategic nuclear systems with offensive capabilities (such as the B-2)

especially are being questioned.

Conservatives, however, assert that Shevardnadze's admission only proves that Western liberals have been duped by the Soviets. They believe that Reagan's arms buildup has made the world more stable, and that the West must maintain its defenses in the event that Gorbachev is replaced by a Soviet hard-liner. Extremists caution that relaxation of international tensions will be used to create a rebirth of the Russian Revolution, or at least culminate in a "Finlandization" of Western Europe. Defense Secretary Richard Cheney points out that the U.S. must be prepared for more than a Soviet adversary. He says that "part of U.S. defense requirements are driven by Soviet capabilities, and the Soviets in fact continue to modernize their strategic nuclear forces. But by no means is the Soviet threat the only thing we have to worry about. We are a global power with global interests and responsibilities."

In the wake of a perceived decrease in the threat of war, public debate in

the U.S. is beginning to shift from nuclear weapons to the issues of housing,

abortion, U.S. policy in Latin America, and environmental concerns. Although the

topics or foci of debate will change, the process of public debate and

demonstration over public policy

unquestionably will continue. The authors

continue to believe that the methodology and insights developed in this paper

should in some measure continue to apply, independent of the subject of the

debate.

Introduction

This work was first presented orally as a father-and-son dialogue. In order to

preserve some of the flavor of that approach, the manuscript is organized

essentially along the lines of the talk, with perspectives from either group

represented upon the work of the other. Our purpose is to shed some new light on

the nuclear weapons debate. Taking positions representative of first one, then

the other, of the communities each author represents, we look at the debate

itself from the vantage point of two participants. Our first assumption is that

each community considers itself to be a "peace activist."

Second, there are members of each community who want to alter the nuclear

balance of terror. The difference in approach is shaped by underlying beliefs

about the U.S., the U.S.S.R., and the nature of man.

One of the two particular subgroups we represent is that of weapons developer. This is not to be confused with policy-maker, because hardware developers and concept-developers are not policy-makers except to the extent that we will discuss later. Likewise, the student campus activist is not to be confused with the academic community per se, nor on-campus think-tanks. The activist represents a particular subgroup of the student community.

In what follows, the role of the nuclear weapons developer is described first; then we present a caricature of the student-activist as seen by the developer. Next, the role of the activist on campus is described, followed by a caricature of the developer as perceived by the campus activist. We then consider some venues of change that might be available to bring about reduction in the "balance of terror." The conclusion draws out some biblical perspectives on the issues identified.

In the abstract we noted that the associated information dealing with a particular weapon may become more important than the weapon itself. A nuclear weapon in our view is a political instrument, and not a war-fighting instrument. Walter Slocombe, former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense, stated that "Deterrence rests not [only] on how the Soviets measure the severity of our retaliation, but also on their judgements about its certainty."1 In other words, how a weapon is perceived and its likelihood of being used determines its effectiveness. U.S. nuclear strategy is deterrence, not mutually assured destruction per se.2-12 In the strategic realm, the U.S. government has said that the U.S. will not strike first...meaning no first-strike on the Soviet homeland. In addition, U.S. targeting strategy is "counterforce," meaning that U.S. nuclear weapons are "aimed" primarily at military targets, in the order of: first, nuclear weapons launch capabilities, then other military targets, followed by targets which comprise the industrial base. Finally, we hope to maintain a "strategic reserve" for rapid termination of hostilities should deterrence fail and nuclear war break out.

In the tactical arena, the strategy maintained with NATO is called "flexible response."13 Under this strategy, if conventional war in Europe should advance to the point that NATO forces are losing, the plan calls for consideration of "controlled escalation" to nuclear in the European theatre.

The cost and morality of these strategies is widely debated, but

participation in the debate is not our purpose

here.11-15 Rather, our purpose is the development

of a perspective on the debate itself, with the outcome of fostering

communication and reducing vitriolic non-listening monologues, in order

ultimately to facilitate means toward a reduction of the balance of terror.

Role of the Developer

Developers of nuclear weapons represent a de facto link

between government policy, the defense industry, and the military, because they

are providing the "tools" to implement policy. Viewed in

this way, the developer as well as the military are extensions of national

policy. Thus, we note with interest the comment by a DoD employee at a protest

demonstration at the Pentagon: "They have the right to protest, but I

have the right to go to work, to make up my own mind. I think they picked the

wrong place to protest. We don't make the policy here; we just follow

orders."15

The procedure by which the weapon developer carries out his task is primarily passive, in the sense that the procedures for doing the job, and the organizations for doing it, are in place. The developer responds to declared military needs and policy communicated from the Department of Defense to the Department of Energy Office of Military Applications. The Secretary of Energy is in the executive branch of the government, at a cabinet-level position. Reporting to the Secretary of Energy is the Assistant Secretary for Defense Programs, followed by the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Military Applications, who transmits requirements to the nuclear weapons labs.

Developers of nuclear weapons represent a

de facto link between

government policy, the defense industry, and the military, because they are

providing the "tools" to implement policy.

The technical work of new weapon development is conducted at the nation's

three nuclear weapon design/development laboratories: Los Alamos, Lawrence

Livermore, and Sandia National Laboratories. Sandia's role is to weaponize the

exploding devices developed by the other two laboratories; that is, to design

the ordnance part of nuclear weapons.

The development of a new nuclear weapon proceeds somewhat as follows: The Department of Defense develops a "statement-of-need" pertaining to a perceived threat. Jointly, the Department of Defense and the Department of Energy then initiate a "Phase-1 Study," which includes a theoretical assessment of the threat, and what kind of weapon is needed to "hold a particular target at risk." In the meantime, exploratory technology is pursued to determine if such a weapon really can be developed. If it is determined that the threat is real, and that the weapon can be developed, the Department of Defense initiates a formal request for development. This request initiates a formalized, institutionalized procedure. Implicit, of course, is the idea of tailor-made nuclear weapons such as earth penetrators. This is the order of the day; "doomsday weapons" or "more bang for the buck" concepts are obsolete.

The nuclear weapons design laboratories are funded on a "level-of-effort" basis meaning that their funding does not depend upon the number of weapon development programs that they have. As a result, there is no reason for them to lobby for more weapons development programs, except for the satisfaction that accompanies successful competition.

In addition to the "institutionalization" described above, the weapons development procedure is essentially objective. That is, it is a technological development process that requires special knowledge and training; it is a R & D process. It requires intelligence information regarding the target and the threat. It is based upon quantifiable data, subject to statistical analysis, simulations, analytical modeling, and testing. Insofar as possible, the power involved in decisions is derived from quantitative information.

The weapons developer usually is convinced that the Soviet Union is driving the arms race. Soviet nuclear weapons and delivery systems are seen as offensive and first-strike postured, while U.S. nuclear forces are perceived as responsive and retaliatory. Although one occasionally hears references to moral superiority, human rights, or individual liberty in context of U.S. defense, such statements come more often from politicians than from technologists. Soviet expansionism is perceived as the greatest threat to peace, and containment of the expansionism is the objective of deterrence; hence, the selection of names such as "Peacekeeper" and "Minuteman."5 The arguments employed by technologists in public debate are usually more quantitative than moral. Whether any of this necessarily classifies most weapons developers as "Hawks" will be addressed in a following section. However, the objective process functions regardless of the personal convictions of the developer.

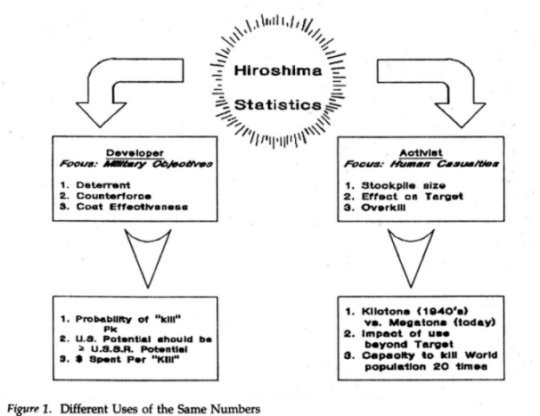

The effectiveness of the U.S. nuclear weapon dropped on Hiroshima measured in terms of its destructive power forms the basis of much of the debate between technologists and activists. The activists and the developers use these numbers very differently. The number of casualties divided by the number of kilotons yields a measure of the effectiveness of the Hiroshima device and, since data is sparse, it is assumed that this measure is representative of all nuclear bursts. The world's stockpile today may have a total explosive yield of perhaps 50,000 megatons. If this tonnage is multiplied by the effectiveness of 4000 kills per kiloton, we must possess enough to kill two hundred billion people (the world population forty times).

The weapons developer will dismiss these arguments by noting that this effectiveness is meaningful only if everyone would conveniently line themselves up under the target area. In fact the world's susceptible population is dispersed over the globe in a non-uniform manner and, moreover, is not necessarily collected near military targets. The argument is analogous to stating that one human male carries enough sperm to impregnate every fertile female in the world.

Figure 1 illustrates this different use of the same numbers. Members of each community will interpret the numbers with a set of presuppositions, which may or may not have been examined critically. The weapons developer will emphasize military objectives, reasoning that "the strategy is deterrence; the targeting is counterforce; and nuclear weapons are cost-effective." He will produce numbers having to do with the probability of target damage or destruction, and that the U.S. potential for retaliation has to be as great as the Soviet threat, else we face an

|

unacceptable risk. He also may mention the

cost to "kill" a target; i.e., "more bang for the

buck" in nuclear weapons. In contrast, the activist will focus on

human and environmental effects of the weapon. We will examine such

presuppositions in a later section.

Caricature of the Campus Activist (from the perspective of the

weapons developer)

The developer is inclined to look upon the activist as academic, with much free

time to dabble in philosophy, especially existential philosophy; he sees him as

a "knee-jerk liberal" in his reaction to allegedly moral

issues, like South Africa, Nicaragua, El Salvador, and "ecology." He is thought to come primarily from the arts and

humanities, less from the sciences. Also, there are a number of perceptions that

might be termed "group issues": use of charismatic speakers,

irrational crowd-excitement, and under-informed listeners who are influenced by

the countercultural media.

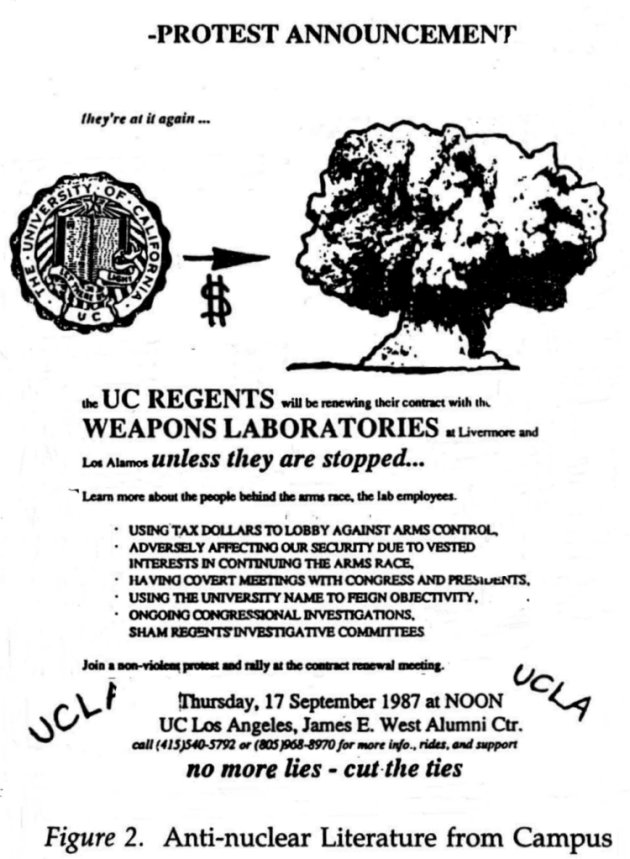

The poster shown in Figure 2 was circulated on the U.C.S.B. campus. The flyer says

"No more Lies; Cut the Ties. They're at it again. Learn more about the people behind the arms race, the lab

employees..." This kind of literature is plentiful on campus, and off campus as well. Another example (Figure 3) was distributed at a

U.C.S.B. "teach-in." This booklet, in which the idea of working in a weapons laboratory is called into question, was offered to incoming engineering students. The booklet was purporting to be objective, but its flavor was obviously slanted toward the negative conclusion.

"Think about your career," the student was challenged. From the perspective of the developer, this was more an appeal to emotion than thought.

The developer tends to see the activist as naive in contrast to the

"real world" of careers, making a living, avoiding poverty,

and family responsibilities. Especially, the activist is perceived to be unaware

of Soviet war preparations. There is also a belief that the students are looking

to establish their identity, separate from their parents. They are thought to be

attracted to experimental living and Bohemian lifestyles. But underneath it all,

the activists are assumed to hold on to a belief that a better world can be

constructed through some rather poorly conceived and inadequately developed

human peace initiative, beginning with disarmament and "love." The rhetorical questions are often hurled:

"Why aren't they at work?" or "Who is paying their

bills while they are demonstrating?"

Role (and Orientation) of the Campus Activist

In this section we attempt to describe the role of the student campus activist,

specifically in distinction to that of the developer. It is a socialized role as

it is practiced on-campus, but without the economic reinforcement that the

developer's role has in the nuclear weapons laboratory. Neither are students'

grades likely to improve from classes missed in order to participate in a rally.

Frequently, activists must be idealists, still considering where they are going

in the future. Because of their strong sense of social consciousness, they

identify with past conscientious objectors and activists of the sixties. It is

important to observe that most activists feel they are without practical (or at

least legal) means of realizing these social and moral goals.

Their role must be active, in the sense that considerable

initiative is required at least of the leaders. No procedures are in

place, other than the ones which are socialized and commonly observed in the

mass-media. The activist must go out of his or her way to initiate the action.

This is opposed to going to one's job in the morning where objective roles are

already in place. The activist has to possibly miss dinner or balance activism

with studies in order to get involved. The procedures of involvement must be

invented. The most effective procedures, as might a television advertisement for

a new product, catch people by surprise. Mimicked procedures such as

demonstrations and teach-ins are becoming less effective than in the recent

past, partly due to saturation of the public consciousness.

The arguments employed by technologists in public debate are

usually more quantitative than moral.

The role of the student campus activist is also subjective. It is plotted by the

exchange of persuasive language rather than the exchange of information as "data." The information is cast in terms of qualitative

units, to the degree that it can inspire "moral outrage" in

the listeners. Some speakers are skilled at generating this kind of response to

the nuclear statistics described above.

Recall that, using the same Hiroshima data in Figure 1, the activist concludes that we have the capacity to "kill the world" many times over. This is something of an absurdity, of course, because in the ideational domain of politics, where weapons function as deterrents, once should be enough. Activist persuasions are based on moral arguments and abstractions, in contrast to the more quantitative arguments of the developer. The activist largely doubts that the Soviet Union is the primary cause of the escalation; the U.S. is perceived as an integral if not primary partner in the arms race. He or she is faced with unresponsive policy-makers and a defense industry that has no interest in de-escalation. Thus, the activist believes that he or she is justified in doing his demonstrating here in the United States.

Activists will base their behavior upon a variety of mental paradigms. One is the opinion that nuclear weapons are a result of an oppressive system, namely, "laissez-faire capitalism," and that this oppression is equal to, if not greater than, that within the "state-capitalist" Soviet Union. Western oppression may be more due to economics than to totalitarian causes, but the end results are believed to produce just as much suffering. This is an important distinction. The activist will argue for moral symmetry between the superpowers, whereas weapon designers tend (when pressed) to argue that the West is relatively more moral (or less immoral).

The developer tends to see the activist as naive in contrast

to the "real world" of careers, making a living, avoiding poverty,

and family responsibilities.

Additionally, activists are suspicious of the information released through the

mass-media, and of press releases by the government. They believe that the

information is subject to management; that is, we as a population are "managed" by our government through information control.

Therefore, activists will seek independent, allegedly more reliable sources of

information. It is believed that rapid protest response, as in the April 1988

U.S. maneuvers in Honduras, is the most effective way to control foreign policy.

The troops were deployed, and within three days there were nationwide campus

demonstrations. Whatever the cause, the troops were withdrawn.

Caricature of the Developer (as seen by the student campus

activist)

In this section we offer a campus activist's view of the weapon developer. In

general, the developer is perceived as "hawkish," even

paramilitary. He or she is assumed to be fear-motivated, buying into the idea of

Soviet expansionism as a threat to the West. Why does the developer still accept

such a viewpoint, even though most activists are convinced that the threat ended

years ago if indeed there ever was a real threat? Largely it is

thought to be due to propaganda the "management"

of information. This "information" protects U.S. interests,

and, to borrow a slogan from a previous era, "makes the world safe for

democracy." Largely, such slogans are attributed to the developer,

though they are produced by politicians. Further, the developer is seen as

preserving his or her self-interests, trying to maintain job security and

lifestyle.

Because of the insulation associated with his vocation, developers are seen

as totally unresponsive to moral arguments. Further, developers seem to have a

form of power which they are unwilling to submit to public debate or scrutiny.

That is, they are perceived as having the power to influence policy in the arms

race through personal input, but use this influence only to advance the arms

race. A recent well-known example is Edward Teller, who is said to have sold the

idea of a "Star-Wars" defensive shield to President Reagan

in one private evening.16 Also, sometimes the

notion surfaces that the developer is merely a pawn in a system controlled by

none (but sustained by the elite), privileged perhaps only to add or not add to

the established political momentum, but unable to change its direction. Each

side thinks that if the other only knew what it knows, the other side would

change its position.

Venues of Change Available to the Developer

In this section we offer, from the perspective of the campus activist, some

possible venues of change for the developer. As we stated in the introduction,

it is agreed that both communities would prefer to move away from the "nuclear reign of terror," although activists are more

likely than developers to believe that it can be induced by unilateral actions.

The venues offered by the activist community take advantage of the developer's

personal influence; that is, by using his or her "specialist-voice" to gain a hearing, he or she can speak to

peers and access policy-makers.

Some lobby groups already exist to offer a forum for the technical professional to speak or work behind the scenes; e.g. Scientists and Engineers for Responsible Technology (SERT), or the Association for Responsible Dissent (ARDIS). There are associations of professionals who have united on the basis of common political views, such as Physicians for Social Responsibility, Union of Concerned Scientists, Computer Professionals for Social Responsibility, or Lawyer's Alliance for Nuclear Arms Control. Another avenue open to professionals is provided by the public policy advisory think-tanks, such as the pro-arms-control Natural Resources Defense Council. Many of these think-tanks are on university campuses. These organizations offer an opportunity for joint involvement between academicians and policy-makers, and they do have an influence on government policy. Developers could join and expand this "dialogue."

Acting individually, one could write to the newspaper editor or participate in forums, public and private. Topics on which the public is eager to hear an informed speaker include nuclear winter, just war, the moral use of nuclear weapons, and a whole host of related subjects. A more radical course of action might include a work-strike or protest over involvement in nuclear development; the risk here is considerably greater because loss of employment can follow. From the perspective of the activist, commitment of this sort is vital if a civil protest is to be meaningful.

If a developer is not prepared for personal involvement he can simply donate

to public-awareness groups. Bread for the World, which is only anti-war

indirectly because of its theme of food instead of armaments for foreign aid, is

a good example. He also can choose in advance how he will respond at a protest

picket line. One serious option would be to return home and notify his employer

of the obstruction. This response is similar to that asked of customers or other

employees at a work-stoppage picket line. The difference, of course, is that the

picketers usually come from elsewhere rather than from within the weapons plant.

Perhaps this is one of the reasons that protest lines seldom, if ever, turn

weapons lab employees away; they usually are impeded rather than deterred. On

the other hand, public involvement is impossible to avoid because one's

lifestyle reflects personal values even in the simple examples of

clothes and bumper stickers. At the very least, a disciplined and consistent

reading program in the subject is essential for broad perspective and openness

to change.

Venues of Change Available to the Student Campus Activist

The student can influence the arms race indirectly simply by choosing to work

only for "socially responsible" organizations, as discussed

in an article by Richard Bube.17 In an earlier

section, we described a booklet from the U.C.S.B. campus that attempted to

influence engineering students away from arms development work. It would be safe

to say that from the perspective of the developer, career choices in the

humanities and arts tend to preclude one from insider participation in the

technological aspects of national policy, and strongly correlate with

anti-nuclear perspectives. On the other hand, a student can prepare himself

academically for participation in one of the public policy think-tanks, or even

choose a career with the government in the policy-making agencies. Most of the

think-tanks will require advanced degrees, and probably some tenure in the arms

control business.

Of course, the traditional organized protest demonstrations, marches, and

blockades are available; but both authors (developer and activist) are

questioning the efficacy of such activities, as alluded to previously. It is

conceded, however, that public demonstrations do tend to bring instant media

coverage, and therefore the publicity desired by the protestors. Such

demonstrations contributed to bringing an end to the war in Viet Nam. Many of

the venues of change suggested for the developer are also available to the

student, and with less personal risk because he or she is less likely to be

fired. Again, a disciplined and broad program of reading from both perspectives

is essential.

Christian Perspectives

We now seek to bring biblical perspectives to bear on these issues. First let us

deal with the traditional stereotype that is commonly applied and will continue

to be applied, "Hawks" vs. "Doves." The

Hawk believes, if the caricatures hold, that the primary cause of war is

military weakness, tempting the militarily superior enemy to strike. The worst

problem to the Hawk is appeasement, with Munich as the classic example. The

Dove, at the other extreme, holds that the primary cause of war is "saber-rattling;" the primary example is Pearl Harbor, where

Japan allegedly saw the U.S. building up an invincible force, and the only

option was to strike first in order to gain some kind of edge in the

Pacific.6

The "Owl," on the other hand, "is a completely different kind of bird."6 The Owl believes that there are many different paths to war, such as a complex set of political actions, or a problem that everybody wanted to back away from but could not or would not. The classic example is the circumstances leading to the outbreak of WWI. Escalation from conventional war to a nuclear war, rather than a sudden strategic strike, might fit within the Owl's concern.

Activists will base their behavior upon a variety of mental paradigms.

Each of these, Hawk, Dove, Owl, is a caricature, or stereotype, primarily applied to policy-makers. As Christians we have to remind ourselves that stereotypes are inadequate. We can't call each other commies, pinkos, war-mongers, or any other label and assume that we have honestly defined someone's views. We must avoid labels and treat people as individuals with worth and dignity, as Christ did. Jesus displayed all three of these characteristics at one time or another. Certainly, he seemed "hawkish" when he overturned the tables of the money-changers and drove them out of the temple with a whip,18 and again when he said "I come not to bring peace but a sword...."19 He appeared to be "dovish" by refusing to speak out in his own defense at his trial,20 and the Sermon on the Mount is usually cited by Christian pacifists as a platform for their belief.21 On the other hand, Jesus usually functioned as an "owl" in dealing with the lawyers, by responding to their questions with "neither-nor" answers.22 In fact, he employed all three of these behavior types at some times and none of them at others. (Note: we must be cognizant of possible differences regarding applications. Some of Jesus' teachings clearly were addressed to individuals rather than states, whereas others have dual application.)

Let us re-focus on arms control. There is a long history, dating back to biblical times, of attempts to limit the kinds of weapons that are legal. Table I gives some examples.

In this fallen world the effectiveness of an arms treaty depends upon whether we can verify compliance. Here is

| Table 1. History of Arms Control

Date Parties 1100

BC

Israel and Philistines Limited Use

of Iron |

an area where a weapons developer can have a very direct input to policy. This is a crucial issue in today's arms control climate. Inability to verify compliance is likely to preclude ratification by the Senate. President Reagan's famous translation of a Russian proverb into "trust, but verify" reflects the approach to arms control of most of the advisors to the Reagan administration.4,5 President Bush, in his Inaugural Address, expanded on this theme by stating that "great nations, like great men, must keep their word. When America says something, America means it, whether an agreement or a treaty or a vow made on marble steps."23 President Bush may have been thinking of Matthew 5:33-37, where we are taught that our "yeas should be yeas and our nays should be nays." In other words, it should be enough for us to tell the Soviet Union, "Yes, we will abide by that treaty." But we are fallen; the need for verification illustrates the state of mankind. U.S. policy-makers tend to believe that the U.S. society is "open" and thus cannot cheat on an arms control treaty, because our action will be published in Aviation Week or debated in the newspapers.7 By contrast, the Soviets are considered to be a "closed" society because the leaders are not accountable to the people. (In fact, the U.S. does insist upon more verification than the Soviets.)

Activists are suspicious of the information released through the

mass-media, and of press releases by the government.

There are many approaches to arms control, depending upon what one believes about them. Conservatives in the U.S urge a cautious "wait and see" response to Gorbachev's glasnost and peristroika policies. A very helpful study was carried out in 1985-86 at Harvard University under the sponsorship of the U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency; see Table II.7 This study examined the beliefs held by an important participant or constituent in the arms control process and disbelieved by another. Some evidence can always be found to

|

support one's beliefs. For example, if one is convinced that bargaining from strength is the best basis for arms control, one is inclined to think that arms control progress takes place only when one side has the military advantage. The Harvard study identified ten questions relating to arms control, providing a helpful tool for understanding the debates.

Organized protest demonstrations, marches, and blockades

are

available; but both authors are questioning the efficacy of such

activities.

Does unilateral restraint (Hypothesis #3) offer the best hope for stopping or reversing the nuclear arms race? For example, if the U.S. decided to cancel the S.D.I. program, would the Soviets offer a responding gesture? Hawks believe that the Soviets will take advantage of concessions by the U.S. The issue of asymmetry, whether military, economic, or geographic, poses another "assumption." Asymmetries certainly exist and might be "codified" by an arms control treaty. Asymmetries must be identified a priori, and quantified if possible, as part of arms control negotiations.

It is probable that arms control agreements succeed only when it is in the interest of both parties to maintain them. Scripture teaches that neither arms control nor nuclear deterrence will bring an end to world conflict. Conflict awaits regardless of what we do with arms control. The situation is analogous to squeezing a balloon. If we squeeze here, the balloon is likely to bulge out somewhere else. The U.S. Department of Defense has made "force modernization" an integral part of its approach to arms control. To some, this strategy is simply an excuse for continuing the arms race. Perhaps, however, efforts at arms control will postpone the final conflict prophesied in Scripture, thereby giving us more time to spread the Gospel. Alternatively, maybe the prophesied conflict will be rendered less damaging because of arms reduction. Perhaps the world will simply become a less dangerous place under the arms control agreements.

From the perspective of the Bible, peace is only available through righteousness. Various proposed "solutions" which do not recognize and address human sin will not be lasting solutions. Here we refer to personal as well as institutional sin. The topic of foreign policy based upon kingdom values has been introduced by others.13 Would anything differ if U.S. foreign policy were based upon pursuit of justice instead of economic self-interest? The Reagan administration maintained the belief that Western social and economic structures are not unjust, or at least are relatively more just; therefore, military solutions to defend them are appropriate. The de facto U.S. policy, in the opinion of the protesters, is to preserve and extend economic dominance. Economic growth, domestic or worldwide, is a fundamental capitalist thesis. Under this rubric capitalism may be called "expansionist."

Questioning authority can be biblically correct if it means that

individuals

are retaining responsibility for moral choices rather than

defaulting

all responsibility to authorities.

Christians, however, can and should involve themselves in government to bring

about change, and Christians are called to be consciences of the state.

Questioning authority can be biblically correct if it means that individuals are

retaining responsibility for moral choices rather than defaulting all

responsibility to authorities.24, 25

However, to

the activist we say, before taking part in a civil disobedience-type protest,

consider that God requires obedience to authority except under extreme

circumstances. Disobedience must cause anguish; this can be a test. If there is

no anguish, perhaps one's involvement is for some other reason than a biblical

one. We ask the developer to consider that simply stating that "I

don't make policy" does not accurately treat either his actual or

potential influence. Each of the authors gained understanding about the other's

peer group during the preparation of this paper. We suggest that dialogue of

this sort, which seeks to identify underlying presuppositions, can provide a

fruitful approach to defusing the hostilities between "establishment" and "anti-establishment"

groups, and might even lead to some unification.

©1990

NOTES

1Walter Slocombe, "The

Countervailing Strategy," International Security,

5, 4:23 (Spring 1981).

2Lawrence Freedman, The

Evolution of Nuclear Strategy (New York: St. Martins Press, 1983).

3Robert Scheer, With Enough Shovels:

Reagan, Bush, and Nuclear War (New York: Random House, 1982).

4Strobe Talbott, Deadly

Gambits: The Reagan Administration and the Stalemate in Arms Control

(New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1984).

5Strobe Talbott, The Master of

the Game: Paul Nitze and the Nuclear Peace (New York: Alfred A. Knopf,

1988).

6Graham T. Allison, Albert Carnesale,

Joseph S. Nye, Jr., Hawks, Doves, and Owls: An Agenda for Avoiding

Nuclear War (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1985).

7Albert Carnesale and Richard Haass,

eds., Superpower Arms Control: Setting the Record Straight

(Cambridge, MA: Ballinger Publishing Company, 1987).

8Freeman Dyson, Weapons and

Hope (New York: Harper and Row, 1984).

9Dan Caldwell, "Arms Control

And Deterrence Strategies," Deterrence In The 1980s: Crisis

and Dilemma (London: Croom Helm, 1985), pp. 183-202.

10Dan Caldwell, "Introduction

to the Transaction Edition," Arms Control and Disarmament

Agreements (New Brunswick: Transaction Books, 1984), pp. xi-xlix.

11Bernard T. Adeney, "Is

Nuclear Deterrence Acceptable?," Transformation, 5,

1:1-8, 18-19 (Jan/Mar 1988).

12Dean C. Curry, "Beyond MAD:

Affirming the Morality and Necessity of Nuclear Deterrence," Transformation, 5, 1:8-17.

13Joseph P. Martino, A Fighting

Chance: The Moral Use of Nuclear Weapons (San Francisco: St. Ignatius

Press, 1988).

14Kenneth A. Bertsch, Linda S. Shaw, The Nuclear Weapons Industry (Washington D.C.: Investor

Responsibility Research Center, Inc. 1984).

15"Protesters Close Pentagon

Entrance," Pentagram, Thursday, Oct. 20, 1988.

16Charles B. Stevens "The

Controversial X-ray Laser," 21st Century, January

1989, p. 44. See also "Lab Scientists Claim GAO Skewed

Views," Valley Times (Livermore, CA) Friday,

February 24, 1989, p. 1A.

17Richard H. Bube, "Crisis of

Conscience for Christians in Science," Perspectives on

Science and Christian Faith, 41, 1:11-19 (March 1989).

18John 2:12-17; Mark 11:15-18.

19Luke 12:49-53.

20Matthew 27:12; Mark 15:5.

21Matthew 5:3-13, 38-48.

22Luke 20:20-28; Mark 11:13-17; Matthew

22:13-22.

23President George Bush, Inaugural

Address, January 20, 1989.

24M. Scott Peck, People Of The

Lie: The Hope for Healing Human Evil (New York: Simon and Schuster,

1983).

25Charles S. Colson, Kingdoms

in Conflict (William Morrow/Zondervan Publishing House, 1987).