Biblical Humanism: The Tacit Grounding of James Clerk Maxwell's Creativity

W. JIM NEIDHARDT

Physics Department

New Jersey Institute of Technology

Newark NJ 07102

From: PSCF 41 (September 1989): 137-142.

W. Jim Neidhardt is

Associate Professor of Physics at New Jersey Institute of Technology. His

professional interests are in quantum physics; systems theory; and

the integration of scientific and Judeo-Christian theological perspectives, both

being forms of personal knowledge as ably pointed out by the scientist philosopher, Michael

Polanyi. He is a member of the American

Physical Society, American Association of Physics Teachers, Sigma Xi, and

a Fellow of the American Scientific Affiliation. He has published

forty-five professional papers. He is also interested in the problems of

educationally deprived college-bound students and has taught a college

level integrated physics-calculus course for Newark high school seniors.

Dr. and Mrs. Neidhardt and their family (all J's) reside

in Randolph, N.J.

Secular humanism, in its insistence that the proper focus of study is humankind alone, has denied a vital dimension of human experience that provides the motivating and integrating drives necessary to inspire genuine scientific and artistic creativity. Biblical humanism restores what is missing in secular humanism by its insistence that true humanism is always defined in a realist context as openness to the totality and richness of all human experience including the religious dimension. It points humankind not only to what is beyond itself but to the full exploration Of external reality, thus bringing into being science, technology and art. A four-stage developmental model of biblical humanism is discussed and illustrated by an extended discussion of a great biblical humanist, James Clerk Maxwell. Some suggestions are made as to how Clerk Maxwell's biblical humanism can be modified to meet the more complex, societal needs of our time.

Introduction

Secular humanism, in its insistence that the proper focus of study is humankind alone, has denied a vital dimension of human experience that provides the motivating and integrating drives necessary to inspire genuine scientific and artistic creativity. If, as in Orwell's 1984. reality is defined by men (leaders of the state), then science can no longer hope to discover limited but real truth with respect to an external reality that exists in some sense independent of human observers. Instead, science becomes merely the formulation of clever "game plans" about man-made arbitrary, hypothetical structures. Such a notion of "science" is no longer a true exploratory activity embedded in curiosity and wonder. Yet, without these latter aspects true human motivation is lacking and, although some minor discoveries may be made because of utilitarian considerations, science as truly creative exploration will eventually- die out. Science is above all a human enterprise, concerned ,with far more than the creation of useful devices: it is a search for truth, a search which such innovative pioneers as Einstein recognized to be an essential aspect of what it means to be truly human.

Biblical humanism1 restores what is missing in secular humanism by its insistence that true humanism is always defined in a realist context as openness to the rich totality of all human experience including its religious dimension. It points humankind not only to what is within the human self but to the full exploration of what lies beyond in external reality. Such an exploration of external reality humbles any honest scientist or artist, for it awakens a sense of awe with respect to external reality's stability of structure and pattern which has the capacity to reveal itself in always new and unexpected ways that are inexhaustible in scope. Through encounter with external reality, including relationships with other people, a person becomes receptive to the biblical insight that the variety, richness, rationality, and unity of human experience points beyond itself to a transcendent, personal dimensionality which is its ground and guide. The Bible reveals that this transcendent, personal grounding of human experience has as its source the creative activity of the Triune God-Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. This living God, a unitary community of divine personal love, is the creator and sustainer of the universe and each person in it. Perceived through the "ears and eyes of faith," the Creation is not God but has imprinted in it the trace of His personal nature. God's personal nature as divine, intelligible love thereby becomes the ground for the form, being, and ultimate meaning of the universe and its creatures. The rationality intrinsic to that form and being is revealed in the biblical insistence that God created and maintains pattern and consistency in the universe with its diversity of form and materials. Thus science, technology, and art are made possible. From this perspective human creativity is seen to be subcreativity; i.e., creativity under God, a creativity within the realm of nature using the potentiality in nature to create new entities. Humankind, made in God's image, uses God-given rational and intuitive abilities to discover hidden likeness in created reality and to bring into being possibilities that reside in what God has already made.

A Developmental Model of Biblical Humanism

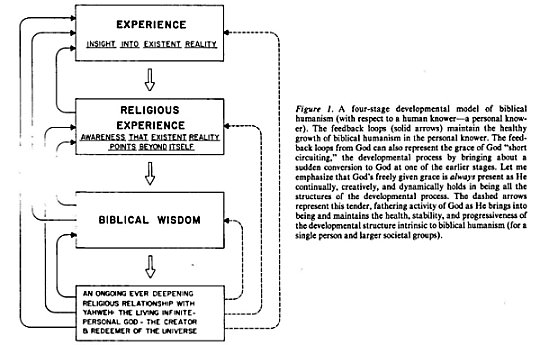

A developmental model

of biblical humanism is illustrated in Figure 1. By development is meant the

unfolding and the re-enfolding of human resources and potentials so that

qualitative changes occur in the way that humankind perceives, understands,

shapes, and modifies the universe being encountered. Development should

be contrasted with growth, which is merely a change in quantity as in an

expansion; i.e., humankind is aware of more facts as time passes. It should be

noted that growth and development are sometimes used interchangeably in

scientific and educational literature.

potentials so that

qualitative changes occur in the way that humankind perceives, understands,

shapes, and modifies the universe being encountered. Development should

be contrasted with growth, which is merely a change in quantity as in an

expansion; i.e., humankind is aware of more facts as time passes. It should be

noted that growth and development are sometimes used interchangeably in

scientific and educational literature.

Some developmental structure is necessary for any model of a healthy biblical humanism in order for it to faithfully represent the richness of human experience as it encounters the inexhaustibility of God's Creation. Biblical humanism encounters reality in a dynamically responsive and adaptive fashion; in such encounters reality can even be modified within the bounds of its own invariant law structures. It is this developmental structure inherent to any biblical humanism that gives it its progressive character. From a Judeo-Christian perspective, God's creative activity toward all Creation is dynamic and purposeful. Biblical humanism's developmental structure, grounded in humankind bearing God's image, reflects this key attribute of divine-personal agency: God's purposeful dynamism. Thus, biblical humanism's developmental structure is, in an ultimate sense, sustained by God's creativity.

This model emphasizes that as a person is open to and reflects upon experience (level 1) one develops in knowledge and understanding, and thereby becomes open to religious experience (level 2) as it is recognized that existent reality has a transcendent dimension; it always "points" beyond itself. Such religious experience, grounded in and a consequence of God's grace, leads to an acceptance of biblical wisdom (level 3) and this biblical insight guides a person into a full, ever-deepening, ongoing dialogue with God (level 4). Further, the religious and higher stages can feed back to the lower stages thereby maintaining a healthy biblical humanism that can continue to develop. In particular a deep relationship with God and the biblical insights that led to that understanding can provide motivating concepts that when fed back will broaden one's exploration of external reality at all experience levels. A specific example of how biblical insights have enriched and can enrich scientific exploration by natural scientists is provided next to illustrate the fruitfulness of this approach. It is particularly striking to me that the physicist, James Clerk Maxwell-a true biblical humanist in every sense of the word-was one of the first scientific investigators of feedback mechanism as a means of controlling system behavior. For it was the feedback of his deeply held, Christian convictions in all areas of his life that, in particular, motivated Clerk Maxwell to incorporate heuristic analogies of a theological nature as vital components of his far-ranging explorations of physical reality. Thus, Clerk Maxwell's scientific creativity exemplifies the feedback model of biblical humanism proposed in Figure 1.

Before continuing, it may be helpful to state why I believe that feedback mechanisms are a necessary component of any model of biblical humanism's developmental structure. If biblical humanism is a viable, creative response to God-given reality it should be progressive, that is, always characterized by stable development. Indeed, one well-known system theorist has put this point well in the title of his book describing the nature of all living, adaptive systems: Grow or Die.2 And, as this book points out in great detail, all healthy biological systems develop due to the establishment of a unique combination of positive and negative feedback with information storage. Positive feedback plays an enhancing, nurturing role in the emergence of more complex, information-laden, living structures; negative feedback provides much needed stability so that the developmental process does not grow out of control in an explosive fashion.3

An Example of Biblical Humanism:

The Life and Work of James Clerk

Maxwell-Relational Concepts in

Christian Theology and Natural Science

A classic example of biblical

humanism is found in the life and work James Clerk Maxwell,

the great Scottish physicist and

Christian.4 As a boy he roamed over the hills and fields of the beautiful

Scottish countryside, and through these experiences he developed a passionate love of

nature in all its richness and variety. Even as a boy he  sought to discover

modes of connection embedded in nature; as an example, he was deeply puzzled by

the question of how an apple turned red under the impact of light.

sought to discover

modes of connection embedded in nature; as an example, he was deeply puzzled by

the question of how an apple turned red under the impact of light.

His boyhood was also embedded in religious experience as his father and mother, who were evangelical, taught him to trust in Jesus Christ, in a very personal way, as God incarnate in a concrete human being who was intrinsically related to the natural order including other human beings-his disciples, strangers, even his enemies-and who continues to be related to us through the living presence of His Spirit.

From a

Judeo-Christian perspective, God's creative activity

toward all

Creation is dynamic

and purposeful.

These boyhood experiences of the unity and variety inherent to nature-physical and biological-coupled with the deeply personal Christian love his parents shared with him, motivated Clerk Maxwell to truly respect the biblical insights concerning the nature of created reality and human kind's place in it. This motivation caused him to search the Bible carefully in order to discover its profound wisdom which led to an ongoing relationship with the living God. This totality of experience was then fed back into all his further attempts to explore and penetrate more deeply into the rich variety of relationships of which nature is composed. In all aspects of his life, Clerk Maxwell linked together his understanding of the God he knew by faith in Jesus Christ with his experience of bow created reality behaved. God in Jesus Christ created the world in his own wisdom; hence, the wisdom from which a Christian learns is the same kind of wisdom that one will find in all aspects of created reality, biological and physical. Thus, Clerk Maxwell's understanding of God the Creator as manifested in Jesus Christ came to exercise a regulating influence over all of his thought. This very biblical regulative insight became a reference from which he tested all of his scientific theories. He thus came to investigate the possibility that the created universe possesses a dynamic and relational rather than static order due to the dynamic, relational nature of its Creator-the Triune God: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit-whose ultimate being is grounded in an active, interpenetrating, interpersonal, loving relationship. It was this deeply held regulative conviction that motivated him to explore more fully dynamic rather than static ways of understanding nature's inherent order.

In particular he looked for a deeper way of interpreting nature that was not linked to the classical, Newtonian notions of mechanical necessity as manifested in isolated particles interacting causally with one another. This led Clerk Maxwell as a mature scientist to develop his theory of the electromagnetic field which brought about a seminal paradigm shift in scientific understanding. In this theory, the field concept was first formally articulated as a relational way of describing particles as never separable from their interactions. The relationships between particles as represented by the continuous, space-filling electromagnetic field were an intrinsic part of what the particles really are. Thus, this relational notion of fields of radiation and their structure became an independent reality in their own right. As Thomas F. Torrance puts it: " . . . the relations he (Clerk Maxwell) referred to were not just imaginary or putative but real relations, relations that belong to reality as much as things (particles) do, for the interrelations of things are, in part at least, constitutive of what they are. Being-constitutive relations of this kind we may well speak of as onto-relations'."5

This field notion concerning physical reality introduced by Clerk Maxwell is heuristically analogous to the biblical concept of the person which was developed by the early Church Fathers in order to understand the biblical evidence pointing to the triune nature of God. Central to the biblical understanding of the person is the reality of human relationships as an integral part of what persons really are. You as a person are not an isolated individual, like the Newtonian particle separated from other autonomous particles. Rather, you as a person are interrelated with others, your parents, your friends, even people with whom you disagree. These interrelationships constitute the very stuff of personal being. Thomas F. Torrance suggests this Christian theological understanding was a possible motivating factor in creating Clerk Maxwell's deep appreciation for Michael Faraday's interpretive vision of charged particles or magnets being interrelated to one another by invisible lines of force which fill all of space.6 If Torrance is correct, this deep appreciation led to Clerk Maxwell's development of the electromagnetic field in order to describe particles as never separable from their interactions.

Thus, insights Clerk Maxwell gained from his ongoing, personal relationship with God were fed back into all his experience with the rich complexity of physical reality. And the exploratory reflection that resulted from the feeding back of these biblical notions enabled Clerk Maxwell to make a great advance in humanity's basic understanding of created, physical reality thereby fulfilling a central goal of biblical humanism-the exploration and further elaboration of truth as revealed in God's created reality. Such biblical humanism as expressed in Clerk Maxwell's life and work manifested itself in a wholeness which is refreshing even to modern critics deeply enmeshed in the impersonal self-centered and individualistic, yet strangely collectivist, strands of this post-Christian age.7 Indeed, one modern biographer, Ivan Tolstoy, describes Clerk Maxwell's biblical humanism as follows:

Maxwell's letters, poems and essays show that his life had many strands, all important to him, all running deep-religion, philosophy, love of family, a sense of duty to his fellow men and women. But science provided the day-by-day framework within which he ordered his existence, and his thought evolved. All his activities were linked; he was strikingly whole. His life is full of interesting continuities. A childhood fascination with contrivances, with bell ringers, with the play of light-these grade into adolescent scientific experiments and musings and almost imperceptibly into serious, brilliant and ultimately revolutionary work in mechanics, color theory and electromagnetism. An early sense of wonder and love of nature never left him and broadening as the years went by, led to an appreciation Of philosophy unique amongst his scientific contemporaries, which gave his work on electricity and magnetism its depth. The love of philosophy was linked to a streak of empiricism which found expression in what was, by virtue of his upbringing and early environment, the only avenue open to him-a traditional Christian faith. From this stem his social views, archaic as they seem to us; they are well meant and part of coherent Weltanschauung. It was all of one piece.8

Let me comment on Clerk Maxwell's "traditional" Christian faith and the "archaic" social involvements that flowed from it. The "archaic" social views to which Tolstoy alludes appear to be Clerk Maxwell's acceptance of traditional political systems; i.e., his refusal to become deeply involved in such things as radical socialist politics. I would affirm that Clerk Maxwell's Christian realism is still a timely (but not "trendy") reaction to the societal problems of his age.

Of course these issues must be rethought in the context of today's much more complex social struggles. Clerk Maxwell's Christian realism, in my opinion, is far more revolutionary than anything proposed by either the most up-to-date political science department or, at the other extreme, the far Right. Clerk Maxwell was truly a deep and creative thinker, as any great physicist must be if he is able to penetrate into the inexhaustible core of physical reality in order to reveal the rich subtleness and inner harmony associated with even "mere" matter. (As Einstein put it, commenting on the God of nature: "God does not wear his heart on his Sleeve," and "God is very deep but never devious."9) Clerk Maxwell's creativity may be looked upon as a profound personal integration, a bringing together of tenacity, the ability to hold on to basic convictions concerning reality, and openness, the ability to be receptive to new ideas . concerning reality.. Symbolically, this may be represented as (tenacity) <->(openness). This integration is a helpful model for gaining insight into all forms of human creativity.

Clerk Maxwell applied his God-given ability as a creative thinker to his understanding of how a Christian should relate to society in terms of Jesus' remark concerning all disciples in the Sermon on the Mount: "You are the salt of the earth, but if the salt has become tasteless how will it be made salty again?" As Clerk Maxwell realized from his own creativity in physics, thought and action are profoundly integrated. He loved and excelled in both experimental and theoretical physics where: (praxis) <-> theory. Accordingly, his Christian perspective motivated him to involve himself personally in teaching applied science to working class people in order that they could understand and work better with the new technologies of the day (in particular the new electricity-based industrialization). This personal involvement of a great scientist expressed as a willingness to give of his time may well have inspired some workers to study more seriously than if they were being taught by a teacher assigned this task by some collective agency, a teacher who saw this assignment as "just a job" with no personal commitment to those being taught. In his more scientific activities, Clerk Maxwell's personal sense of duty toward editing the work of other scientists could have inspired some of his colleagues to have greater dedication to science seen as a cooperative venture where each scientist builds upon and depends upon the work of others. Clerk Maxwell would have thought today's "star system" of research very odd. Is it not possible that Clerk Maxwell's taking valuable time from his own scientific creativity may have even spurred his creativity on by providing time for his mind to assimilate basic concepts (incubation

Clerk Maxwell realized from his own creativity in physics: thought and action are profoundly integrated.

periods of rest), also exposing him to the stimulus of novel and often practical problems which alerted his active mind to new concepts and analogies (cross-fertilization of ideas)? Thus, the apparent drudgery of routine academic assignments may actually have stimulated new ways of thinking in Clerk Maxwell's very holistic mind. In short, Clerk Maxwell's biblical humanism expressed as an openness to all reality manifested through service to others benefited his own scientific growth in understanding. At the same time, being a concrete human and exemplar of Christ's healing, mediating love, Clerk Maxwell applied such to the problems of the Victorian society in which he worked.

How do these notions of biblical humanism as expressed in the life and work of James Clerk Maxwell apply to today's much more complex post-Christian society? Let us clearly recognize that biblical humanism is fundamentally an openness to all of human experience. In Clerk Maxwell, this humanism expressed itself in a remarkable life of exploration and stewardship with respect to God's Creation coupled with a life of service to others. Today both scientists and biblical scholars have a better understanding of the structural evil inherent in all realities, including human societies. If these insights could be incorporated with Clerk Maxwell's insights as to appropriate person-based responses to the complexities of societal problems, a new kind of social activism embedded in Christian realism could emerge. Such a social concern would not be centered in an individualistic, self-centered collectivism but would be centered in a personal community approach to social problems. Such a person-centered community would be embedded in a Christian understanding of the uniqueness of each person as never separable from his or her intrinsic interrelatedness to others-family, friends, neighbors, or the larger society. It should be emphasized that this biblical humanism is truly' I radical," as it points to a concept at the root of any understanding of what a human society really is-the biblical notion of personhood as a relational concept in which all relationships are embedded in love. This biblical understanding motivates humankind to concentrate their efforts on the establishment not of a society of isolated individuals but of a community of persons involved with one another and caring for one another. Christians, in particular, should prayerfully ask God to help in better reflecting this aspect of humankind as being made in the image of God. For God is truly a Triune community in unity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit in eternal relationships of divine love toward one other.

Earlier in this paper I gave a long quote of Ivan Tolstoy, a secular biographer of Clerk Maxwell. who expressed great admiration and puzzlement with respect to the dynamic holism intrinsic to every aspect of Clerk Maxwell's active and productive life. Could it be that Clerk Maxwell, as a Christian layman, continually affirmed the dynamic presence of Jesus Christ in his life by allowing Christ's living presence to permeate and mediate into all aspects of his encounters with God-given reality-human and non-human alike? Indeed, Clerk Maxwell was very much in the tradition of Blaise Pascal, another great realist and scientist, who, as a Christian layman, led a very rich and productive wholistic life properly understood in the context of the culture of his time.10

It is interesting that this same wholism appears in the life and work of the recently deceased realist philosopher of science, Michael Polanyi, whose continual openness to the richness of human experience resulting from human encounters with reality led him to discover philosophical insights in substantial resonance with the Christian realism of Clerk Maxwell and Pascal. Such a biblical humanism as Clerk Maxwell's was responsive to the richness of human experience of reality in a manner that another great Christian realist, St. Paul, deemed very appropriate: "Finally brethren, whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is right, whatever is pure, whatever is of good repute, if there be any excellence and anything worthy of praise, let your mind dwell on these things" (Philippians 4:8). Indeed, it would be very profitable and fitting to reread Tolstoy's quote on Clerk Maxwell's holistic life in light of the wisdom contained in Philippians 4:8.

©1989

NOTES

1 A beautiful statement on Christian humanism is given in Eternity, January, 1982, pp. 15-22.

2 Lockland, George T., Grow or Die. (New York: Random House, 1973).

3 Ibid.; and Parsegian, V. L., This Cybemetic World of Men, Machines and Earth Systetm. (New York: Doubleday & Co., 1973).

4. The primary sources of this section on Clerk Maxwell are (I am deeply

indebted to Thomas Torrance for the insights presented):

a. Torrance, Thomas F., "Christian Faith and Physical Science in the Thought of James Clerk Maxwell," in Transformance and Convegence in the Frame of Knowledge. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1984), pp.215-242.

b. Torrance, Thomas F., Faith and PhysicslMemorial Lectures, Feb. 27, 1983. Gordon College Media Center, 55 Grapevine Road, Wenham, MA, 01984.

c. Campbell, Lewis and Garnett, William, The Life of James Clerk Maxwell. (London: Macmillan and Co., 1882). Available from Johnson Reprint Corporation, New York.

d. Tolstoy, Ivan, James Clerk Maxwell-A Biography. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1981).

5. Torrance, "Christian Faith

and Physical Science in the Thought of James Clerk Maxwell."

6. ibid.

7. Tolstoy, op. oft.

8. Ibid., pp. l959.

9. Torrance, Thomas F., The Ground and Grammar of Theology. (Charlottesville: The University of Virginia Press, 1980), pp. 119-145.

10. Contrary to common opinion, it can be argued that Pascal became a truly integrated thinker after his deep religious conversion. He did leave scientific and mathematical pursuits for a short time after his conversion but returned to them even as he faced deteriorating health and the challenge to use his formidable writing skills for the defence of the Christian faith. This later effort culminated in his unfinished but masterful notes toward a Christian apologetic, The Penskes. For a full discussion of his complex yet deeply integrated Christian life we Mortimer, Ernest, Blaise Pascal: The Life & Works of a Realist, (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1959).