Science

in Christian Perspective

Science

in Christian Perspective Science

in Christian Perspective

Science

in Christian Perspective

From: JASA 38 (December 1986):244-250

The spectrum of possible viewpoints on origins is explored and reclassified on the basis of three levels of questions. First, what is the relationship of God to the natural world? Second, how might God act (or not act) to produce novelty and direction? Third, what is the pattern of appearance?

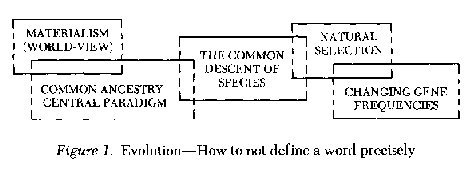

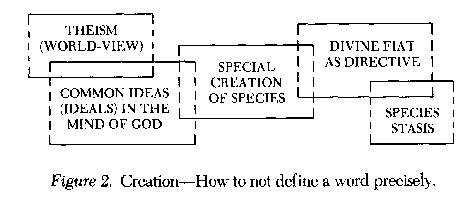

Few disagreements in modern thought are as confusing as the debate over the relationship of God to the creation of the natural world. Certainly real issues are at stake, but one gropes after them, confused by clouds of rhetorical smoke. The confusion could be much reduced by clearer definitions from both "sides." Both 11 evolutionists" and "creationists" do much categorical pigeon-holing and give multiple definitions to their banner words-evolution and creation. For example (Fig. 1), evolution has been defined as "fact" (observed change in gene frequency); as "mechanism" (neoDarwinian natural selection); as "scenario" (the descent of species from common ancestors by transformation); as a "central paradigm" ("Nothing in Biology makes sense except in the light of evolution"-Dobzhansky, 1973), and as a materialistic "weltanschaung" ("The whole of reality is evolution, a single process of selftransformation. "-Huxley, 1953). The meaning of the word "Creation" has been equally abused in exactly the same way (see Fig. 2). What seems to be needed for communication is some new way to classify viewpoints. The goal of this paper is the beginning of such a 11 taxonomy of creation."

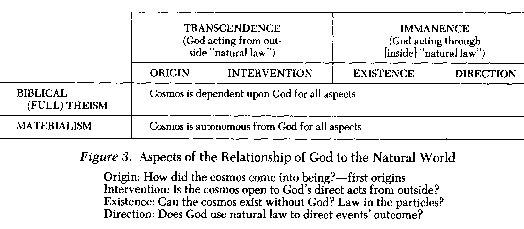

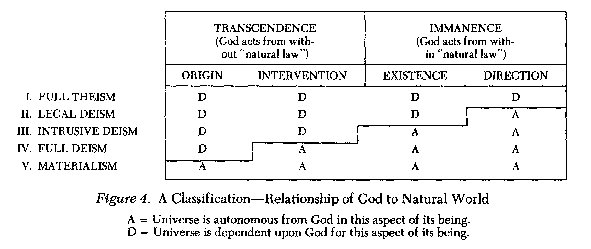

The Relationship of God to the Natural WorldThe first principle of systematics is that some differences in structure are more important than others. Part of the fuel for the "origins" debate has been a lack of insight into which conceptual differences are central and distinctive, and which are secondary and peripheral. I suggest that in such a proposed classification the world-view is central. In relation to science, the most important conceptual distinctive in world-views is the relationship between the cosmos (matter) and Deity. I will discuss four distinct aspects of this relationship, and will distinguish a spectrum of five world-views, based on the presumed degree of autonomy of the natural order. This classification is summarized in Figures 3 and 4. The dominant world-view of our age among scientists is materialistic naturalism, which holds the universe to be completely autonomous in every aspect of its existence. On the other hand, both the ancient Hebrews and the early modern scientists (Robert Boyle, for instance) held a full theism, viewing the universe as completely dependent in every aspect (see Fig. 3) (Klaaren, 1977). The three "intermediate" views listed in Figure 4 hold the cosmos to be autonomous in some senses, dependent in others. Figure 4 is not intended to be an exhaustive classification, but is limited to viewpoints which consider a Deity (if existing) to be an eternal, omnipotent spirit other than the cosmos in essence (i.e., pantheistic views are not considered.)

The first two aspects of reality shown in Figure 4, origin and intervention, apply to the possibility of ranscendent divine activity, meaning divine activity which is "ex machina." God acts from outside the natural order, contra "natural law." These aspects are the origin of the system (cosmos, matter, etc.) and the openness of the existing system (cosmos) to outside intervention or intrusion. The second two aspects, existence and direction, apply to the possibility of immanent divine activity; Le, God acting in concert with the natural order, through "natural law." These aspects therefore imply a certain relationship between 11 natural law" and God. They concern the continuing existence and behavior of matter and the possibility of directive activity taking place through (using) natural law. In the next few paragraphs, I will briefly explore the meaning of autonomy versus dependence for each aspect.

Few ultimate options exist for the origin of the cosmos. A truly autonomous origin (Fig. 4; origin) could only be thought to happen in one way: the material system must be in some sense cyclic. Either mass/ energy is eternal (presumably oscillating), or energy is fed backward "past" time (the hyper-dimensional space-time continuum) to emerge at the "creation." Neither of these is a commonly held view at present. Most materialists are simply willing to live with mystery, accepting a universe generating itself ex nihilo via the laws of nature. The alternative viewpoint, dependent origins, posits that a sufficient cause for the initial creation of the system must be outside the system. The Christian view of God is especially satisfying because He has both the will to act and sufficient power. One implication of a dependent origin is that the laws governing the structure of the cosmos are expressions of His will.

Autonomy of the cosmos from outside intrusion, the second aspect (Fig. 4; intervention), is a statement that there can be no "singularities," points where physical events within the cosmos must be explained in terms of causes from outside the cosmos. The cosmos is either considered to be "all there is" or to be somehow closed to the reality without; or, alternately, the reality without is considered to be of such a nature that it would never "interfere" with lawful processes of the cosmos. If the cosmos is considered open to intrusive action, natural law is not denied, although there is a possibility of events which can not be explained completely from causes within the system. In that case, science could only describe the boundaries of the singularity, rather like a description of a black hole.

The third aspect of reality, existence (Fig. 4), represents a watershed in world-views. A cosmos autonomous in existence does not need a sustaining Deity in order to continue in existence. The law governing its continuance and operation exists directly in its elementary particles. Such a cosmos can live, though God be dead. Natural law itself is autonomous. There can be no doubt that the Biblical writers view "nature" as completely dependent upon the continuing will and action of God. In such a viewpoint natural law itself is the orderly expression of the presently active will of God, and is therefore exterior to the system, rather than being "on the particle." If God is dead, or if His "mind wanders," the universe is non-existent. Due to the positivistic heritage of the last century, we have an instinctive feeling that science is only possible if natural law is an intrinsic characteristic of the particle. However, Klaaren (1977) has argued cogently that it was the view that law was contingent to the will of God which led to the rise of modern science. Science simply requires law, not a particular sort of law.

The fourth aspect, direction (Fig. 4), looks even deeper into the concept of natural law, and may be even more foreign to the contemporary mindset. If law is considered to be a rigid framework which can not, or will not, permit directive action on the part of God, then the universe is autonomous. Even a sustaining law based on God's active will can be thought of being as completely deterministic and non-directive as the most materialistic of viewpoints. Must one hold such a view if the world is to be made safe for science? Despite the

David L. Wilcox received a PhD in Population Genetics from Penn State University in 1981. He has taught five years for Edinboro State College and eleven years for Eastern College. He currently chairs A.S.A.'s Creation Commission, and has presented papers dealing with the theoretical nature of selective fitness and the use of Biblical perspectives in analyzing biological theory.

fears of the twentieth century, modern science began

with a world-view which considered the Providential

direction of the events of nature fully acceptable. Nor

was this direction seen as antagonistic to the concept of

secondary causes, but, rather, supportive of them

(Klaaren, 1977). This is the position spelled out in the

Westminster Confession of Faith, for instance. A

dependent universe, in this sense, is one in which God continuously directs all natural events, without tension, through natural law. I think it important to remember

that this is no peripheral idea, but one central to the

scriptural picture of Divine lordship. Surely we expect

Him to act in this fashion if we pray requesting Him to

meet specific needs.

continuously directs all natural events, without tension, through natural law. I think it important to remember

that this is no peripheral idea, but one central to the

scriptural picture of Divine lordship. Surely we expect

Him to act in this fashion if we pray requesting Him to

meet specific needs.

How Might Novelty and Direction Be Produced?

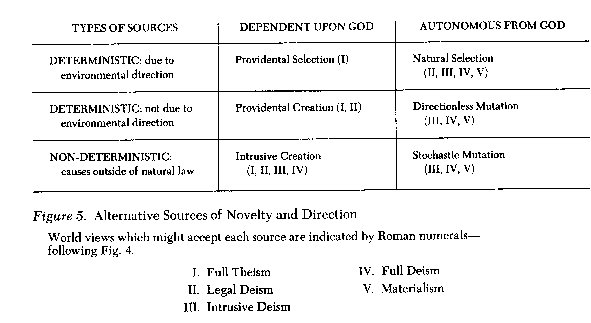

Central to the debate concerning biological origins are the questions of the source of novelty and the source of direction. Such questions can form a second level of our "taxonomic hierarchy," as illustrated in Figure 5. Materialists, as well as deists and theists, differ on these questions. If true randomness is characteristic of the movement of atomic particles, such "stochastic" events may add novelty, and even provide direction. If the cosmos is truly deterministic, all events and structures were implicit in the nature of the origin, although many of these events may look random to our limited viewpoint. The most popular viewpoint is a hybrid one, considering novelty to be due to random events (mutation) and direction to be locally deterministic (natural selection).

Full deism may be divided into the same groups as

materialism. If the cosmos is deterministic, then all the events were programmed at creation to unroll in time.

Both novelty and direction would be fixed by the initial

program. Direction is set by the characteristics of

natural law, and novelty by the initial state of the

cosmos. If the cosmos is stochastic, then God could

program potentials, but could not know how the results

would work out, Although significant novelty and

direction would be implicit from the beginning, the

stochastic openness would contribute to both in determining outcomes. One unique differentiation for biology within full deism would be the mode of species

creation; from nothing, from abiotic matter, or from a

(just) previously created species. In the first two cases,

similarity would be due only to common ideas in God's

mind. In the third, it would also indicate "common

ancestry" (although not due to "natural" processes).

events were programmed at creation to unroll in time.

Both novelty and direction would be fixed by the initial

program. Direction is set by the characteristics of

natural law, and novelty by the initial state of the

cosmos. If the cosmos is stochastic, then God could

program potentials, but could not know how the results

would work out, Although significant novelty and

direction would be implicit from the beginning, the

stochastic openness would contribute to both in determining outcomes. One unique differentiation for biology within full deism would be the mode of species

creation; from nothing, from abiotic matter, or from a

(just) previously created species. In the first two cases,

similarity would be due only to common ideas in God's

mind. In the third, it would also indicate "common

ancestry" (although not due to "natural" processes).

Intrusive deism may also be divided into deterministic and stochastic viewpoints. In the deterministic view, all events are still programmed for both novelty and direction. However, instead of all programming being done at the time of origin, it is also done at many small intrusive "mini-origins" as time passes. A stochastic view would tend to view intrusive events as not only creative and directive, but also as possibly corrective of "wrong" novelty input from stochastic processes (or perhaps, free will).

Legal deists will tend to look at the universe in almost exactly the same ways that the intrusive deists do. However, they will view intervention in a fundamentally different fashion, since they differ in their concept of natural law. In intrusive intervention, God moves against the resistance of natural law which continues in force. The legal deist, however, will view intervention as local points where natural law is temporarily cancelled (or changed) in favor of some alternative divine action. Creation is, of course, that point when God first began to act in the fashion of natural law.

Full theists are significantly different in their viewpoint, since law itself is viewed as an avenue through

which God works directively and continuously. Novelty could therefore arise by programming of the initial

structures, by "guided" deterministic events, by "chosen" stochastic events, and by "outside" intervention

(that which appeared to be an intrusive event). Theistic

viewpoints might be distinguished on the basis of which

of these mechanisms are emphasized. It would, however, be hard in a given instance to distinguish between

God's various modes of operation, since all are God's

hand in action. "Laws" are not seen as a description of

what God has made, but rather of His present and free

actions. His creative Word of command still actively

reverberates from the structure of reality.

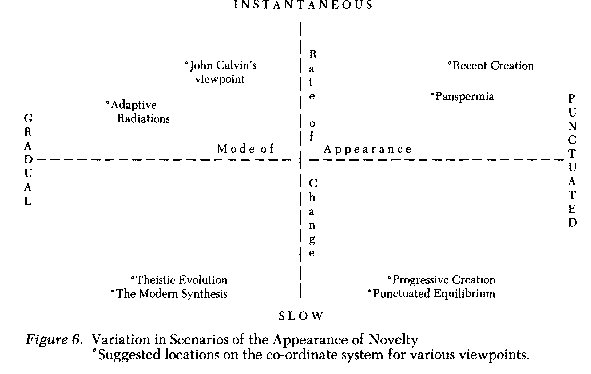

What Is the Pattern of Appearance?

Given the "phyla" of world-views (what is the relationship of God to the world?), and the "classes" of

sources of novelty (How does God act upon the world?),

I would suggest that the logical "orders" are the

scenarios of the appearance of novelty (When did He

do it?). The four most extreme possibilities for what the

fossil record shows would be as follows: 1) all species

appeared suddenly at about the same time, 2) all

species appeared suddenly, but at different times, 3) all

species appeared gradually at different times, and 4) all

species appeared gradually about the same time. Intermediate views are possible, of course, as illustrated in

Figure 6. One may hold any scenario of appearance

with each of the world-views in Figure 4, although

acceptable explanations for the observed phenoma

would vary.

Space will not permit a complete description of all

combinations, but, as a brief illustration, consider the possible explanations for the sudden appearance of a

species. A materialist might explain it as due to random

events which produced a successfully changed regulatory genome, or to deterministic events which reached

a threshold somewhere (in environment or genome)

and caused a sudden change in state. A full deist might

agree, but point ont that the species was planned for in

the initial state of the universe, or at least was a

reasonable possibility. An intrusive deist might accept

the above as possibilities, but also suggest that new

programming might have taken place at that point in

geological time. A legal deist would agree, but would

possible explanations for the sudden appearance of a

species. A materialist might explain it as due to random

events which produced a successfully changed regulatory genome, or to deterministic events which reached

a threshold somewhere (in environment or genome)

and caused a sudden change in state. A full deist might

agree, but point ont that the species was planned for in

the initial state of the universe, or at least was a

reasonable possibility. An intrusive deist might accept

the above as possibilities, but also suggest that new

programming might have taken place at that point in

geological time. A legal deist would agree, but would emphasize that new programming could have been

caused by a local change in the laws of nature which

would allow species modification. The theist would

probably admit that all the above are possible explanations, but would point out that in any case we are only

distinguishing between the various overlapping modes

of action which God might use.

emphasize that new programming could have been

caused by a local change in the laws of nature which

would allow species modification. The theist would

probably admit that all the above are possible explanations, but would point out that in any case we are only

distinguishing between the various overlapping modes

of action which God might use.

Synthesis: Clarifying the Debate

In closing this discussion, I will try to apply the framework which has been developed to four of the positions which are most commonly distinguished in the origins debate (Pun, 1982). These positions (mentioned in Fig. 6) are usually entitled Recent (sometimes called Fiat or Special) Creation(ism), Progressive Creation(ism), Theistic Evolution(ism), and Atheistic Evolution(ism), and are often characterized as a series going from the best to the worst. There is, of course, a difference of opinion concerning which end is "best" and which end is "worst." You can sometimes tell a writer's orientation by the end to which be attaches "ism." In any case, it becomes evident that these terms do not represent single clear world-views, but heterogenous and contradictory assemblages.

Atheistic Evolution(ism), as usually defined, is

merely materialism; i.e., the world-view that the universe is completely autonomous and therefore God is

not necessary. In the minds of many, it is also identified exclusively with the continuous appearance scenario.

stochastic novelty formation and deterministic direction; i.e., the Modern Synthesis as evolutionary mechanism. Such a confusion of categories gives the impression that the neutral mutation debate, the proposal of

punctuated equilibrium, or "directed panspermia, represent covert attempts on the part of certain scientists to subvert or to compromise with a theistic position. This simply is not true. These theories of mechanism are alternate scenarios or explanations, equally

derivative from a mechanistic world-view.

exclusively with the continuous appearance scenario.

stochastic novelty formation and deterministic direction; i.e., the Modern Synthesis as evolutionary mechanism. Such a confusion of categories gives the impression that the neutral mutation debate, the proposal of

punctuated equilibrium, or "directed panspermia, represent covert attempts on the part of certain scientists to subvert or to compromise with a theistic position. This simply is not true. These theories of mechanism are alternate scenarios or explanations, equally

derivative from a mechanistic world-view.

Recent Creation(ism), as usually described, is an assemblage of viewpoints which agree only on a specif ic scenario of the timing of creation (a single sudden appearance), along with a definite rejection of autonomy for the cosmos in origin. It is not a cohesive world-view, however, since supporters can be full, intrusive, or legal deists, or theists. Currently, their most popular view of the nature of "created kinds" admits that change is possible, but only within the limits of the genetic potentials built into the initial population. (The original "kinds" are not usually identified with species by modern "recent creationists," but most are reluctant to go beyond genera, or perhaps sub-families, in trying to identify them.) Since God's present providential activity in the biological world is not seen as directive and as having purpose, this particular concept of the limits to change is a fully deistic and deterministic concept of the source of novelty, (although individuals who hold this view in biology are often "theistic" in other areas of thought.) A true theist can not accept the idea that any event in any realm can occur except due to the plan and present action of God. The physical source of the new "kind" might be thought to be new matter, abiotic material, or a previously created "kind." In any case, the creation process is held to be initiating, very rapid, nonreproducable and not due to the laws of nature. An older concept of species stasis (circa 1840) identified the limits of change with a "platonic ideal" species image in the mind of God, and was therefore more clearly theistic, since God was thought to be continuously acting (via natural law) to bring the (fugitive) species back to its designed ideal, or to recreate it if it became extinct.

Progressive creation(ism) also seems to represent a heterogenous set of world views which are agreed on the concept that species ("kinds") appear suddenly (special creation), but at considerable intervals, due to intrusive divine acts. Progressive creationists include both intrusive deists, legal deists and full theists. Variation in view exists regarding the source of novelty, with the most common view similar to that of the recent creationist. The "kind" is considered to be initially programmed with no later modification, a typical intrusive deistic viewpoint. As in recent creationism, the physical source of a new "kind" might be thought to be a new matter, abiotic material, or a previously created "kind," and the creation process is held to be interventional, very rapid, and non-reproducable.

A full deist could propose that such a pattern is due to an initially programmed punctuated equilibrium, or a theist, that it represents a divinely directed punctuated equilibrium. Such views would not be included in this viewpoint (as I understand its proponents, at least), despite species origins being both sudden and due to God, because they would still be due to natural law rather than to intrusive intervention. Such viewpoints would usually be cast into the next category.

In any inadequate system of classification, some

category must pick up items which do not fit anywhere.

That is probably the most accurate definition of what

people mean by Theistic Evolution(ism). Everyone has

a somewhat different, often pejorative, definition,

depending upon exactly how they define the other

three categories. In general, all concede that "Theistic

Evolutionists" accept both the existence of God, and

11

regular evolution." For some, that means a full deism

with an otherwise autonomous cosmos evolving in a

fully materialistic fashion. Others view it as "the God of

the Gaps," a variant of intrusive deism in which

materialistic evolution is occasionally helped along by

divine intervention. Since these views concede autonomy of law to the material particle, they ought not to be

called "theistic." Recent creationists often mean by the

term anyone who believes in God (in any sense), yet

questions the sudden appearance moael, thereby

including the progressive creationists, who reject evolution as completely as they do. Materialists may mean

anyone who is "scientist first, religious second." Such a

potpourri is not a position, but a conceptual trash can.

Is a theistic evolutionary scenario, in the real meaning of the words, possible? Not unless one f irst limits the

meaning of "evolution" to a single concept, for

instance, to the descent of one species from another by

natural law. In this I follow distinctions and definitions

used by Charles Hodge, the well known Princeton

theologian of the last century, as be considered Darwin's theories (1874). Anyone who is a fully biblical

theist must consider ordinary processes controlled by

natural law to be as completely and deliberately the

wonderful acts of God as any miracle, equally contingent upon His free and unhindered will. Miracles, after

all, are given as signs, not as demonstrations of God's

normal activities. What then might a "theistic evolution" look like? One example of a possible theistic

scenario would be this: God designs and produces the

cosmos, and all of life, by immediately and directly

controlled gradual continuous change due to microcreation (mutation) and providential direction (natural

selection) using only natural law. (In parallel with two

previous terms, such a view could be called "Continuous Creation" after the scenario of appearance which it

advocates.) It could not be held by any of the three

forms of deism because it depends upon God directing

through natural events. Only a full theist could hold it.

The true "scandal" of theism is not that it concedes too

much to materialism, but that it refuses to concede so

much as the spin of a single electron.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the tension between the materialistic

naturalism of our day, and the theistic viewpoint of the

scripture may be resolved in one of two fashions. Either

one may choose a world-view half-way between the

two, as illustrated in Figure 4; or one may consider

" naturalism" as a special simplified sub-set of theism,

just as Newtonian physics forms a special simplified

sub-set of Einsteinian physics. Materialistic explanations are useful within the limits set by their simplifying

assumptions. These simplifying assumptions are the a

priori framework of twentieth century science. Theistic

or deistic explanations therefore are not acceptable,

which is fine as long as the materialistic model of

explanation (episteme) is recognized as a model. The

value of a model, a simplified representation of reality, is to allow a more complete exploration of how well tie

assumptions of the model match reality. The danger of any model is the tendency to identify the model

with the reality which it represents.

In this paper, I have been proposing a classification of "scientific" views or models (interpretations of nature). Naturally one will choose corresponding scriptural models (interpretations of scripture) (Barnett and Phillips, 1985). Such models do not show one-for-one, identity, however. Differing models of what scripture means may be held with the same scientific model, and people with identical scriptural interpretations man, differ in their scientific models. In general, the Scriptures' proclamations about the nature of God are easier to understand than its occasional statements about the specific techniques He used at particular times.

I see two things as critical for this debate. First, the

Scriptures are unalterably theistic, so we have no reaoptions in world-view. For example, we must not

adopt

deistic positions to limit God's possible activities to our

favorite scenario. Second, we need a humble spirit

concerning the correctness of our conclusions-and

exclusions. This paper has presented three levels of

questions which serve to differentiate various position,

on origins, giving as many as one hundred distinctly

different positions which might be (and commonly are

held on this subject. It is not surprising that the debate

has become rigid and polarized. Complexity bewilders

and discourages. Simplicity has a seductive beauty.

(Un)fortunately, neither God, nor His universe, are as

simple as we are.

REFERENCES

Barnett, S. F. and W. G. Phillips. 1985. Genesis and Origins: Focus on

Interpretation. Presbyterian Journal, 44: 5-10.

Dobzbansky, T. 1973. Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of

evolution. American Biology Teacher, 35:125-129.

Hodge, C. 1874. What is Darwinism?, as quoted in The Princeton Theology

1812-1921, ed. M. A. Noll. IM. Presbyterian and Reformed Publishers,

Phillipsburg, New Jersey.

Huxley, J. S. 1953, Evolution in Action. Harper and Brothers, New York.

Klaaren, E. M. 1977. Religious Origins of Modern Science. W. B. Eerdmans,

Grand Rapids.

Pun, P. T. 1982. Evolution, Nature and Scripture in Conflict? Zondervan,

Grand Rapids.