Science

in Christian Perspective

Science

in Christian Perspective Science

in Christian Perspective

Science

in Christian Perspective

Response to Evil: A Christian Dilemma

RICHARD H. BUBE

Department of Materials Science and Engineering

Stanford University

Stanford, California 94305

From: JASA 35 December 1983): 225-234.

In previous installments we have considered a number of ethical issues, difficult issues in which inputs from both science and biblical revelation are needed in order to arrive at a responsible Christian plan of action. What is the appropriate way to bring such a series to an end? What is the ultimate Christian ethical issue? Where is the greatest paradox, the greatest dilemma to be found?

An appealing way to conclude a series on science and the whole person is to look to the future and present a discussion of the interaction between science and eschatology. I have already considered these specific issues1 and shall not repeat them here. It is sufficient to realize that the Christian faces the future neither as one who drops out of a conflict that does not concern him, nor as one who plans to win the conflict before the return of Christ, but rather as one who walks into the darkness hand in hand with Christ, striving in faith to remain faithful no matter what comes. And as the Christian seeks to do this in today's and tomorrow's world, he runs directly into the fundamental question: "What is the Christian response to evil in the world, specifically the evil of other people?"

This question poses the dilemma that is perhaps the most critical and the most difficult for the actual everyday living out of the Christian life. Christians are widely split on its answer. The attitude toward science and the applications of science depend crucially on its answer. It goes to the very heart of the Christian Gospel and to the meaning of that Gospel in the Christian life. It probes the authenticity of the Christian message and demands that we put even our lives on the line.

What is the nature of this dilemma? It is simply this. On the one hand we have the clear New Testament teaching that the role of the disciple of Christ is to be the role of love, embracing not only friend and family, but extending even to the enemy. The reason for this is fundamental: love is the only authentic and practical way to overcome evil in this world. Such love may require personal sacrifice, even the laying down of our lives. Jesus faced the evil of the world in exactly this way as our example: the only way in which He could break the power of evil and lay open the road to forgiveness and restoration of fellowship with God was to lay down His life out of love. If He had done anything short of this, God's plan of salvation would not have been achieved.

IOn the other hand we have the clear biblical teaching that the role of the disciple of Christ is to be the protector of the helpless, the defender of the oppressed: the one who in the presence of the evil of the world demonstrates the love of God by being willing to defend the defenseless against the evil of other people (even if this means choosing the lesser of two evils?). A Christian may be willing to sacrifice him/herself rather than respond violently to the perpetration of evil, but does he/she have the right (the duty) to sacrifice the lives of others as well, even those who do not share in the Christian commitment?

This issue is so involved that we cannot get a grasp on it without first realizing the many questions that must be answered. To begin, therefore, let us simply list what seem to be the most crucial questions.

A Few Fundamental Questions1. What is the relationship between the Old Testament divine approval of warfare and the New Testament ethic of love and non-resistance?

2. Is a life lived in response to the New Testament ethic of love necessarily a life of non-violence?

3. is the life of love described by Jesus intended for an "ideal world" or for this very sinful world in which we live?

4. In the final analysis can evil ultimately be overcome through any other means than longsuffering and active love?

5. Is the life of love described by Jesus intended only for individuals, or for collections of individuals in family, community, state, and national entity?

6. What is the general relationship between Christian ethics for individuals and Christian ethics (if there are such) for national entities?

7. How is the life of love described by Jesus to be reconciled with self-defense or the defense of suffering others?

8. If a person who f aces evil with no other weapon than love that is willing to suffer, dies or is killed in the attempt, does this demonstrate that such suffering love is a failure?

9. How do we summarize the responsibility of the Christian toward those who need help, who are being afflicted by others, or who are threatened with affliction by others?

10. What constraints are there on the actions a Christian

can take to aid those needing help? Is "Just War Theory" an

adequate Christian position?

11. Is a "just war" possible in a real evil world?

12. Is an unjust war justified in an unjust world?

13. Can a "Just War" be fought in a nuclear age?

14. Can a Christian plan to fight a nuclear war?

15. Can a Christian pretend to plan to fight a nuclear war? What does he do if his bluff is called?

This list could probably be extended to a much longer one without exhausting the issues involved in all their nuances. Question 4 appears to be the most fundamental one for the Christian to answer, although all of the issues appear to be intensified many times over by the reality of nuclear warfare.

The Uniqueness of the Christian ResponseIt is absolutely essential that it be realized at the very outset that we seek here the Christian response to these questions. This means that we ask only a single question: What is the significance of the teaching and life of Jesus Christ for these issues? Or, alternatively, bow do we expect Jesus Christ Himself to respond if placed in the situations that Christians find themselves today?

It may seem at first that this approach is inadequate. We may prefer to ask other questions instead. Does this make sense? Will it work? Will it achieve the goals that we desire? Will it prevent suffering? Is it a practical approach? If we follow it, will we probably lose our desires, our freedom, and perhaps even our lives? if we are to be faithful to our goal, however, we must ask none of these questions-at least not in such a way that they dictate the answers that we give.

We are assuming that the Christian is called to follow in the steps of Christ here and now. If we conclude, even for a moment, that this life is not going to work-what are we saying about the authenticity of Jesus as the Christ, the Son of God? If we say that this life is foolish and incapable of being responsibly followed-what are we saying about the trustworthiness of the One whom we proclaim to accept as Lord and Savior? We need to regard these implications with utmost seriousness.

The Words of JesusWe seek the Christian response to our question in three fundamental sources: (1) the words of Jesus, (2) the teaching of the New Testament writers, and (3) the example of Jesus.

The words of Jesus related to our question are found primarily in the fifth chapter of Matthew, together with the parallel section in Luke 6:27-36.

The seventh beatitude in Matthew 5:9 proclaims the basic truth, "Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God." To be a peacemaker is therefore classed along with hungering and thirsting for righteousness, being merciful, being pure in heart, and being persecuted and reviled for righteousness and Jesus' sake.

Later in the Sermon on the Mount we find the second section in Matthew 5:38-48. Formerly it was thought appropriate to exact retribution in the form of an eye for an eye, or a tooth for a tooth; Jesus calls upon us not to exact retribution, but to go so far in the opposite direction that we actually open ourselves up to second slaps, and respond to law suits with double the amount asked.

Formerly it was thought appropriate to love one's friends but to hate one's enemies. Jesus again pushes to the extreme and tells us that we must love our enemies and pray for them who persecute us. Why? So that we may really live as the children of our Father. Loving those who love us is no real test of our Christian commitment; the real test comes when Jesus calls us to love those who desire our harm.

We seek here the Christian response to these questions. This means that we ask only a single question: What is the significance of the teaching and life of Jesus Christ for these issues?

Several other words of Jesus are found in the Gospel of John that bear on this same question, although less directly. In John 15:19, 17:16 and 18:36, Jesus emphasizes the difference between His Kingdom and the kingdoms of this world. He tells the Christian that he has been chosen out of this world to live according to the constitution of another heavenly Kingdom. In this world the servants of the king fight on his behalf, but in Jesus' Kingdom His servants do not fight.

Possible Contrary PassagesIn his consideration of this issue Dombrowski2 has given a concise summary of some of the objections viewed against a simple interpretation of these words of Jesus because of other

This continuing series of articles is based on courses given at Stanford University, Fuller Theological Seminary, Regent College, Menlo Park Presbyterian Church, Foothill Covenant Church and Los Altos Union Presbyterian Church. Previous articles were published as follows. 1. "Science Isn't Everything," March (1976 ), pp. 33-37. 2. "Science Isn't Nothing," June (1976), pp. 82-87. 3. "The Philosophy and Practice of Science," September (1976 ), pp. 127-132. 4. "Pseudo-Science and Pseudo- Theology. (A) Cult and Occult," March (1977 ), pp. Z2-28. 5. "Pseudo-Science and Pseudo- Theology. (B) Scientific Theology," September (1977 ), pp. 124-129. 6. "Pseudo-Science and Pseudo-Theology. (C) Cosmic Consciousness," December (1977), pp. 164-174. 7. "Man Come of Age?" June (1978), pp. 81-87. 8. "Ethical Guidelines," September (1978 ), pp. 134-141. 9. "The. Significance of Being Human," March (1979), pp. 37-43. 10. "Human Sexuality. (A) Are Times A'Changing?" June (1979), pp. 106-112. 11. "Human Sexuality. (B) Love and Law," September (1979 ), pp. 153-157. 12. "Creation. (A) How Should Genesis Be Interpreted?" March (1980 ), pp. 34-39. 13. "Creation. (B) Understanding Creation and Evolution," September (1980 ), pp. 174-178.14. "Determination and Free Will. (A) Scientific Description and Human Choice," March (1981 ), pp. 42-45. 15. "Determinism and Free Will. (B) Crime Punishment and Responsibility," June (1978), pp. 105-112.16. "Abortion," September (1981 ), pp. 158-165. 17. "Euthanasia," March (1982), pp. 29-33. 18. "Biological Control of Human Life," December (1982 ), pp. 325-4331. 19. "Energy and the Environment. (A) Is Energy a Christian Issue?" March (1983 ), pp. 33-37. 20. "Energy and the Environment. (B) Barriers to Responsibility," June (1983), pp. 92-100. 21. "Energy and the Environment. (C) Christian Concern on Nuclear Energy and Warfare," September (1983), pp. 168-175.

passages supposed to present contrary views.

One of these is concerned with Jesus' cleansing of the temple (Matthew 21:12, 13; Mark 11:15-17; Luke 19:45, 46; John 2:13-17). We need not be concerned here with whether the cleansing referred to in John is the same or an earlier cleansing from that referred to in the synoptic gospels. The argument is often made that these passages show Jesus in violent action, driving out the moneychangers from the temple with a whip. Actually, however, the whip is not mentioned at all in the synoptic gospels, and the authors do not tell us what means Jesus used to drive the moneychangers out. They certainly give no evidence that Jesus used physical violence against human beings in this eff ort. John does mention the "whip," which is probably a lash made out of rushes, but only in the context of *using it to drive out the sheep and cattle. John does not mention Jesus' driving out the moneychangers themselves explicitly at all, and certainly gives no indication that He drove them out with physical violence. These passages do show that Jesus' apparent commitment to the way of love and non-violence does not mean that He therefore does not oppose injustice or misunderstanding in a sinful world, of which we shall have more to say later.

It is true that Jesus spoke of wars continuing to the end of this age. In Luke 21:9, for example, he said, "And when you hear of wars and tumults, do not be terrified; for this must first take place, but the end will not be at once. " Jesus' speaking prophetically in this way of wars in the future certainly does not imply that such wars are legitimate, or that Christians are called upon to participate in them. In the following section of Luke 21:10-19, for example, Jesus does say what is expected of Christians when nation rises against nation, and when they are persecuted: "This will be a time for you to bear testimony."

In Luke 22:35-38, the author records the somewhat puzzling words of Jesus, "And let him who has no sword sell his mantle and buy one." When His disciples replied, "Look, Lord, here are two swords," Jesus replied, "It is enough." Should these words be taken literally as advice for martial preparation in spite of Jesus' other teachings? Many commentators join Leon Morris~ in concluding that these words of Jesus are figurative, His "graphic way of bringing it home that the disciples face a situation of grave peril. " The disciples did not understand this, and speaking in terms of material arms, indicated that they could come up with only two swords. Jesus' words, "It is enough," are not an acceptance of the two swords, suggests Morris, but rather a dismissal of the whole subject that the disciples had so badly misunderstood. Any other interpretation seems out of context indeed in view of Jesus' immediate response to Peter's use of one of these swords shortly thereafter, "Put your sword back into its place; for all who take the sword will perish by the sword." (Matt. 26:52) And, having healed the ear of the slave of the high priest, Jesus said, "No more of this!" (Luke 22:51) Are these words Jesus' message to each of use who would use earthly violence to defend Him and His people?

Finally there are those who would argue that Jesus' advice to pay tribute to Caesar from what is Caesar's (Matt. 22:1522; Mark 12:13-17; Luke 20:20-26) is His condoning of a Christian's participation in violence and warfare on behalf on the state. But such an argument must assume that it is the state's prerogative to demand that a Christian be involved in violence and warfare-and this is precisely the issue often at stake. Jesus is willing to offer a coin to Caesar, but the text does not indicate that he allowed Himself to be tricked into giving any more than that.

Understanding of the New Testament WritersThe New Testament writers elaborate further on this theme presented in the teaching of Jesus in such a way as to bring home more clearly its meaning and application for Christians. The two central passages are to be found in Romans 12 and I Peter 2, although several other supporting passages may also be adduced.

It is significant that Romans 12 immediately precedes the passage most often cited to support Christian participation in warfare in Romans 13. In Romans 12:2 Paul calls for the Christian to be transformed and not conformed to this world, so that the will of God may be understood and followed. Practical expression of this transformation is given in Romans 12:14-21. The words of Jesus are echoed in Rom. 12:14, "Bless those who persecute you; bless and do not curse them." Then in Rom. 12:17, "Repay no one evil for evil;- in Rom. 12:19, "Beloved, never avenge yourselves, but leave it to the wrath of God." Finally Paul quotes Proverbs 25:21, 22, "If your enemy is hungry, feed him; if he is thirsty, give him drink; for by so doing you will heap burning coals upon his head." To this Paul adds, "Do not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good." We consider the connection between Romans 12 and 13 a little further on in this paper.

This same theme is developed also in I Peter 2:19-24. "But if when you do right and suffer for it you take it patiently, you have God's approval. For to this you have been called, because Christ also suffered for you, leaving you an example, that you should follow in his steps ... when he suffered, he did not threaten; but be trusted to him who judgest justly. He himself bore our sins in his body on the tree, that we might die to sin and live to righteousness. "

The theme of the duties of citizenship in His Kingdom is also echoed by the New Testament writers. In 11 Corinthians 10:3, 4, Paul points out that Christians are not engaged in a worldly war nor with the weapons of a worldly war. Constrasted to those who have "minds set on earthly things," are the Christians for whom ". . . our commonwealth is in heaven, and from it we await a Savior, the Lord Jesus Christ. " (Philippians 3:19, 20) Our citizenship has been changed so that we are citizens of "the kingdom of his beloved Son." (Colossians 2:13)

I John 2:5, 6 reminds us of the foundational truth that the assurance of our salvation is connected with our following Christ: "he who says he abides in him ought to walk in the same way in which he walked."

The Incredible Biblical TeachingIf we put all of this biblical teaching together, we have one of the most incredible claims ever made: that ultimate victory over evil even in this most sinful world can be achieved only through longsuffering and active love. It is not that we should love only those who are part of our family, community or nation-we should, of course, but our enemies as well. It is not that we should exercise love as long as we can without suffering as a consequence-but without end. It is not that love will carry us only so far in a sinful world and that after that we must resort to force and violence-but that if we seek genuine victory in Christ we must persevere in love far beyond the boundaries of human reason and "common sense" that has not come into fellowship with Christ.

Incredible to the earthly mind? Of course! Who would dare to be a peacemaker in the midst of a warring world that looks at peacemakers with contempt? Who would willingly suffer abuse and persecution for the sake of Christ when it could be avoided by violent resistance? Who would presume to attempt to love one's enemies without making some kind of semantic switch so that "love" really means "destroy"? Who would be so bold as to live in this world while holding fast to citizenship in another? Who can bring oneself to bless one's persecutors? To bring food to one who desires your destruction, or to offer drink to one who works for your abuse? Who could be so naive as to attempt to offer good in response to the evil poured upon one? Who would willingly forego his .1 rights" and suffer for someone unjustly? Who?

The Example of JesusIn view of the obvious idealistic character of the above claims, it is of ten argued that Jesus did not mean what He said, at least not in the way that we might think He meant it. His teaching should be considered as applicable in the everyday situations of local personal interactions-unless, of course, even here the offense is too great-but not in the larger environment of government or international affairs. To follow His teaching literally is to open the doors to all kinds of injustice and suffering, for evil people will interpret a loving response to evil as an invitation to perpetrate more evil without penalty. Bullies understand only force, not nonviolence. Unless we stand up for our rights with whatever violence may be needed, we can be sure that we will be walked over. In the words of Christian author, Harold 0. J. Brown, "In a fallen world where man's heart is inclined to evil, the counsel of peace at any price is a recipe for subjugation."4 In an earlier publication (which I now bring into question) I have myself sided with Brown when he says, "But some provocations are too great to ignore," and have recommended a violent response to terrorists .5 Any other response seems too impractical, too visionary, too unrealistic, too irresponsible. And so we are forced back to the Christian response, and the example of Jesus Christ Himself. What we see is the overwhelming evidence that the central fact of the Christian faith itself speaks to us unambiguously of Jesus' total conformity between teaching and action.

In an insightful treatment of this subject, Date Aukerman6 draws our attention to Matthew 26:31, "You will all fall away because of me this night," or in the King James Version, "All ye shall be offended because of me this night." In the Greek the verb here translated "fall away" or "be offended" is the verb skandalizb, which means to put a stumbling block in the way of, to cause to stumble, or to set a trap for. A simple transliteration would read, "You will all be scandalized because of me this night." Why were they to be scandalized that night? It was to these words of Jesus that Peter replied, "Even if all shall be scandalized because of you, I will never be scandalized." What was the scandal here referred to? It is the scandal of the cross, of the defenselessness of Jesus and the defenselessness of His disciples. Peter would have preferred to go down fighting; be was not at all prepared to continue without fighting.

His coming was God's ultimate exposure, defenselessness, vulnerability. Reconciliation between God and his adversaries could come, not through his annihilating them, not by his overpowering and coercing them, not by his keeping them at a safe distance or his maintaining a shield to hold off their mad attacks. Reconciliation could be brought about only as he has drawn near to the enemy, met them, spoken with them, showed them himself. It could come only through defenselessness, vulnerability, the cross. God did not defend himself. The Father did not defend the Son. Jesus drew near his enemies; he met them. He was wounded, smitten, pierced, done away with by human beings. When we had done our worst, God came back with his best.6

It is of interest to note that it is exactly at this point that Islam rejects the Christian record; the Koran tells us that Jesus did not die but was rescued by the Fatber.7 So also Christ crucified was a stumbling block (skandalon) to the Jews (I Corinthians 1:23).

Jesus came to give the final answer to evil, not just in words but also in living example and achievement. His final answer-the very basis of the entire Christian Gospel-was that He was willing to suffer and die in order to achieve the purpose of God in salvation. As a human being, Christ lost-He was put to death. As a practical politician, Christ failed-His movement was threatened, His leadership removed, and His voice silenced. Every practical instinct of His followers told them that the last thing they should do is let Him go to His death. Peter protested (Matt. 16:23) and then later tried to fight to prevent it. Jesus' counsel was steadfast: this was not the path He had come to walk; this was not the way of His Kingdom. As far as the world was concerned, it seemed that evil triumphed on Calvary; all the instincts of human beings to attempt to live responsibly cry out against it. Yet nothing is clearer in the biblical revelation than that this day, this event, this death was part of the eternal plan of God to raise up a people to Himself, forgiven and newly created in Christ-wbo would have to become a scandal in order to achieve His purpose.

And it is we who are called to "follow in his steps" and "to walk in the same way in which he walked."

Christian Responsibility for OthersAlthough Christians may be willing to accept, at least in principle, defenselessness for themselves as they follow Christ (although this is often the crucial problem), it does not seem responsible on their part to demand defenselessness of others. Thus the question arises: What is the Christian response to the suffering of others? Does not at least this responsibility open the door to justification of physical violence in defense of others?

Jesus faced such choices when He was tempted by Satan in the wilderness, and turned His back on what was offered as the easy road in order to follow the road to obedience.

Aukerman6 goes on in his discussion of Jesus as skandalon to remind us that this skandalon concerned not only the defenselessness of Jesus, but also the defenselessness of His disciples. if it was a scandal and a stumbling-block that Jesus should die, it was a continuing scandal that Jesus should appear to leave His disciples without protection. One by one, and many hundreds and thousands with them, fell to the sword and the beast, to persecution, imprisonment, torture and privation (Hebrews 11:35-38). But in not providing physical and violent protection against the evils of the world, Jesus did not leave His disciples alone. In their hour of greatest need Jesus prayed for them (Luke 22:31, 32), not as the second best that He could do, but as the best. And it was out of concern for the basic welfare of His disciples, that He did not turn aside from the way of the cross; rather He defended them through obedience to the Father and the way of the cross. When Christians resort to physical violence to protect others in need, bow much violence do they do to the ultimate cause and witness of Christ, how many are lost forever because of this misguided attempt to secure safety at the expense of disobedience?

A Christian commitment to physical non-violence should never be interpreted to mean that Christians are to passively endure injustice, evil, and unrigbteousness around them. We do not serve as salt and light unless we are spicy and illuminating. The way of Jesus does Dot lead to withdrawal from the world or adoption of the world's methods. We are called to exercise all the creativity we can muster in order to transform evil into good. The Gospels record many confrontations that Jesus was involved in, often at the risk of His life. What did He do when he was present as a group of accusers were about to stone a woman to death? (John 8:2-11) Did He call down fire from heaven, or rally His disciples to fight off the accusers so that the woman could be delivered? instead He used the resources at His disposal and won a temporary victory, a victory that really resulted in the direction of the accusers' anger against Him rather than the woman. So also Jesus defended His disciples in Gethsemane by drawing the attack to Himself rather than to them (John 18:8). Aukerman concludes,

There is in all of us an inclination to see the use of tangible weapons to fend off physical attack as more real, substantial, and practical than the spiritual warfare described in Ephesians 6. But the most decisive battle in history was the one between Jesus and the powers of darkness; his was the supreme defending of us all. If in biblical perspective we truly see that and the relative indecisiveness of all military battles, we have basis for discerning what for us and those dearest to us is the critically needed defense: "They have triumphed over him (Satan) by the blood of the Lamb and by the witness of their martyrdom, because even in the face of death they would not cling to life" (Revelation 12: 11).7

Taylor and Sider8 emphasize the active role that Christians are to play in this world.

just as the commitment to justice carries Christians into struggles to defend the rights of the poor and the oppressed, so our commitment to justice should express itself in strong resistance to aggression, invasion, or occupation ... Christians are called to be reconcilers, but also to actively resist injustice, evil, and oppression.

If we put all of this biblical teaching together, we have one of the most incredible claims ever made: that ultimate victory over evil even in this most sinful world can be achieved only through longsuffering and active love.

They suggest that guides to how Christians can meet these calls can be found in the life of the early church in which Christians lived in a region occupied by a foreign invader who used military force to guarantee its power. In spite of all the horrors of persecution in this environment, Christians actively resisted and struggled against the imposition of evil; many of them paid for it with their lives. Chrysostom, a church leader of the fourth century, said,

What, then, ought we not to resist an evil? Indeed we ought; but not b~ retaliation. Christ has commanded us to give up ourselves to suffering wrongfully, for thus we shall prevail over evil. For one fire is not quenched by another fire, but fire by water.9

To all such suggestions comes a common answer, But will it work? Is it not just foolish to expect such behavior to do anything in an evil and unjust world except lead to greater injustice and oppression?

And so we are driven of necessity to the fundamental question: Was Jesus wrong? Is self-giving love the only truly redemptive response to evil to which every Christian is called? is the use of physical violence to respond to evil only the progenitor of further violence and greater evil? Should we love, feed, and give drink to our enemy-or should we harm, maim, and kill our enemy?

There is no lack of evidence in the world that testifies to the conclusion that Jesus was indeed wrong. He died on the cross for peace and love, but the world is as full of sin and hatred as before He died. For two thousand years the way of Christ has had a chance to solve the world's problems, and it might seem to have failed miserably; today the world seems as untouched by self-giving love as in the days of Jesus Himself.

Nor need one reach out into international affairs or even national interactions to come up with evidence that Jesus was wrong. It is a fundamental experience of our daily lives in personal interactions that failing to meet a bully with physical force invites only our own abuse. When I was a youngster (not then a Christian), a neighbor boy took great delight in tormenting me. He would draw a line and dare me to cross it. I faced the dilemma of not crossing it and suffering the humility of cowardice, or of crossing it and getting beat up. Over the passage of a few years I grew bigger than he, and one night I faced him with the fury of flailing fists as my Mother cheered me on. The whole experience was cathartic; it was clear-or so it might seem-that Jesus was wrong. After that show of physical force, he did not bully me again. Had violence triumphed where love would have failed?

Many have felt the challenge of the totally unendurable and turned to violence as a kind of last resort in extremum. Dietrich Bonhoeffer lived a life of ardent pacifism until he came to the point where he felt compelled to join the plot to assassinate Hitler and replace him with a responsible head of state. As Bonhoeffer himself said, Is it the duty of the Church only to apply band-aids to the injured when a madman comes down the street swinging an axe, or is it the duty of the Church to stop the madman with whatever means are necessary? Jesus also faced a madman and called out the demons within him (Luke 8:26-33). But, we protest, He did it because He could exercise the power of God-and we cannot. Perhaps that is our problem.

This is no minor question. There have been some who denied that Jesus could be the Son of God because they believed Him to be mistaken about the future course of the world and His own return. But if we say by our lives that Jesus was wrong about the central message He brought and lived concerning the interaction between God and evil, do we have any Christianity left at all? If the Resurrection was not the vindication in time of the ultimate power of self-giving love over the forces of evil, what was it?

Christian Perspectives on WarConsideration of these issues through the years has resulted in the crystallization of several different Christian perspectives on war. An excellent overview of four principal approaches is given in War: Four Christian Views.10 This book also lists a bibliography of over a hundred major references to the topic of Christianity and war. The four perspectives treated are: (1) Biblical Nonresistance (from a dispensational perspective), (2) Christian Pacifism, (3) just War theory, and (4) the Crusade or Preventive War. One of the strengths of the book is that it presents the position in the words of the advocates of each of these position, and then allows advocates of the competing positions to offer critiques.

We can present only the briefest of overviews here.Herman Hoyt presents the position of Biblical Nonresistance from the viewpoint of a dispensational theology. He finds that nonresistance is only for Christians and not for the nations of the world or human government during this age. God permits human governments to engage in war, but He limits Christian in this respect. Thus Christians can serve a war effort, but only through noncombatant roles.

Myron Augsburger follows a position for Christian Pacifism much like that outlined in the earlier portions of this installment. In contrast to humanity's choice of force for the settlement of disputes, Jesus calls us to a better way. He also makes a point I have reflected on in the past:11 can a Christian responsibly participate in a war in which he is called upon to take the life of another Christian, two individuals for whom Christ died living out between them the very antithesis of what He died for?

Arthur Holmes presents the just War theory. He recognizes that war is an evil, but argues that all evil cannot be avoided. If unjust violence and aggression exist and we do nothing about it, then we are implicated in its consequences. The concept of just War theory is an ideal for all people. It seeks to set bounds to this form of evil. It is based on seven major requirements: (1) just cause, (2) just intention, (3) last resort, (4) formal declaration, (5) limited objectives, (6) proportionate means, and (7) noncombatant immunity. He seeks to interpret John 18:1-11 and Matt. 5:38-48 in terms of Romans 13, providing a general basis for the government's use of force.

Harold Brown develops the idea of Preventive War as "a war that is begun not in response to an act of aggression, but in anticipation of it," and a Crusade as "a war that is begun not in response to a present act of aggression, but as the atttempt to set right a past act." He presents a defense of war under limited situations as the lesser of two evils, as the only practical way of living responsibly in a sinful world.

If for the moment we neglect all the details, however

important they may be, these four perspectives come down to

just two: (1) Christians should follow the express teaching and

example of Jesus Christ, even though every worldly estimate

of the immediate practical success of such an approach is

debatable at best;

(2)

the teachings and example of Jesus

Christ are ideals toward which Christians should strive, but in

the real sinful world in which we live, true Christian responsibility requires us to engage in the lesser of two evils. Hoyt and

Augsburger expound what they believe the biblical teaching

to be; Holmes and Brown expound why practical and responsible living must be guided by other considerations as well. If

Augsburger says of Brown's position, "The cross shows that

we do not have to win or succeed (as the world speaks of

success), but rather that we must simply be faithful," Brown

in return replies, "My disagreement with Augsburger is with

his contention that in this present evil, fallen world God

expects and requires pacifism. This contention is, it seems to

me, utopian, and not biblical."

And so again-was Jesus wrong? Or have we misundertood the message of His words, His life, His death and His

Resurrection? Can we avoid a choice between these two

unwelcome options?

"If We Can justify the Police, We Can justify the

Army ,12

We return now to Romans

13,

that keystone passage of

government authority and the use of force to punish the

evildoer. No single passage bears more weight in the development of alternative interpretations of Jesus' words and example than this chapter. We remember that it follows Romans

12:19,

with its injunction, "Vengeance is mine, I will repay,

says the Lord." It seems clear that Romans

13:4

ties in with

this, "for he (the ruler) is God's servant for your good. But if

you do wrong, be afraid, for he does not bear the sword in

vain; he is the servant of God to execute his wrath on the

wrongdoer." In a similar vein Peter writes, "Be subject ... to

governors as sent by him to punish those who do wrong and to

praise those who do right." (I Peter

2:14)

We recognize first that these passages deal specifically with

police" action within a country, and not with armies and

warfare between countries. Hence the argument that titles

this section: if it is possible to justify the police, then it is

possible to justify an army. Or, in a reverse argument

ad

absurdurn,

if physical violence is always forbidden, then the

government is forbidden to have a police force, and this

violates both common sense and Scripture; therefore an army

is justified. We must look carefully both at the context of the

passages in Romans and I Peter, and then at the claim that to

be content with police action within a country necessarily

leads one to be content with warfare between countries.

In both contexts above the biblical author is exhorting Christians to live in such a way that they may be without blame. With a new sense of freedom in Christ, Christians might well be tempted to throw off all the symbols of authority of the culture in which they lived. Having Christ as King, they might be tempted to renounce or disregard all human government. Not only would this be displeasing to God in its own right, but it would be a very dangerous argument to place in the hands of Christianity's enemies. Women might be tempted to disregard their husbands, taxpayers might be tempted to withhold taxes, citizens might be tempted to ignore laws, servants might be tempted to challenge masters, and in many other ways Christians might antagonize and provide poor witness to the society in which they lived. By acting in these ways, Christians would be providing ammunition for the enemies of Christ who tried to portray them as an antisocial movement. They sought in many ways to charge Christians with being disloyal citizens and an enemy of the powers that be. Paul and Peter urge Christians not to fall victim to this temptation, but instead to retain a sense of God's action through the authorities in power. They were to recognize that God did act to punish evildoers through the authorities in power and to respect that authority. It is clear that in the context two groups are in mind: there are the Christians and their attitude toward the authorities, and there are the authorities who punish evildoers. The text does not give us the input we need to cross over and ask what is the proper activity of Christians if they themselves are the authorities. Peter makes clear the purpose of these remarks, when he says, "For it is God's will that by doing right you should put to silence the ignorance of foolish men. Live as free men, yet without using your freedom as a pretext for evil; but live as servants of God." (I Peter 2:15)

As a matter of record, there is no evidence of a Christian soldier after New Testament times until about 170 AD. There is no record of believers in positions of authority under the Roman government until about 250 AD. There is no acceptance of the holy Christian warrior engaged in sacred Crusades until the 11th century." The intent of these passages cannot be stretched beyond their application, therefore, to infallibly lead to guidance on some of the questions under consideration here.

We can, I believe, grant without great debate the essential necessity for a "police" action with human society corrupted by evil and sinfulness. We likewise grant the appropriateness of the restraint of evil within carefully defined guidelines. We can also, I believe, grant the possibility of Christians serving in such police capacities. But we cannot grant in any way the fallacious argument that acceptance of a police force logically ties us to the acceptance of an army. There are critical differences between a police force and an army, and these must not be forgotten.

Examination of the conditions of just War theory shows that they will be satisfied by any responsible police force operating today (which does not overlook the fact that many so-called "police forces" around the world today are nothing more than internal armies and hence subject to the critique against armies rather than against police per se). On the contrary, it is doubtful whether any war ever fought with armies satisfied one-half of the Just War theory requirements, certainly no war fought in recent years nor likely to be fought in the future.

The difference between a police force and an army is nowhere more clearly seen than in the attitude toward - noncombatants." Any authentic police force today is based on the commitment to bring no harm to innocent bystanders; in fact, if this happens by accident, a lengthy investigation is involved to be sure that the harm could not have been avoided. Warfare, certainly in recent years, is totally unconcerned about the distinction between "combatants" and "noncombatants "-what pillaging and raping armies did not accomplish in the past, saturation bombing and the possibility of nuclear bombing make intrinsic to the future.

Police action is limited by desire and administration to appropriate means," and the use of force beyond that judged necessary for the specific restraint of lawbreakers is quick to receive criticism and responsive action. In modern warfare there are no "proportionate means;" total destiuction, unconditional surrender, and complete collapse of the enemy have become the goals. If any army attempts to practice anything less, it is sure to meet with severe criticism.

Police forces are specifically under civilian control; although armies pretend to be under civilian control, this pretense is seldom tested and military matters are run by military people to satisfy a military perspective.

If there were to be any correlation at all between Christian

acceptance of an authentic police force and Christian acceptance of a military force, it would have to be limited to a

military force designed and committed only for the restraint

of evil without the infliction of physical violence on other

persons. Whether such a military force could be considered

viable in anything except a near-utopian world is another

question that must be faced.

How the Nuclear Age Makes Other Arguments

Superfluous

When we add to this discussion and all the inputs of the previous sections the fact that we live in the nuclear age, when any war may lead to an all out nuclear holocaust, we are brought to several well defined conclusions. Even advocates of a just War approach take pause and begin to speak about 11 nuclear pacifism."14,15

The facts of nuclear war bring home to us as never before the fundamental truths of Jesus' teaching and example: attempts to deal with evil by the use of evil can produce only evil. In the past, we may have had the appearances of a better world as the consequence of warfare. The nuclear age shows this to be the illusion it has always been.

We no longer are faced with the choice between responding to human aggression and suffering by the physical

violence of war, or the apparent standing by while human

.

.

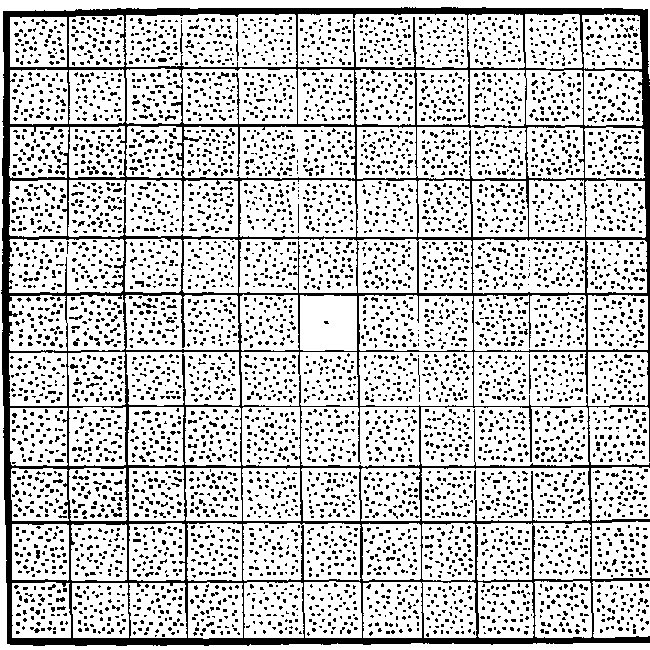

Table 1

The dot in the center square above represents all of the firepower of World War 11: three megatons. The other dots represent the number of World War 11 equivalents that now exist in nuclear weapons. This ig 18,000 megatons or the firepower of 6,000 World War Hs. The United States and the Soviets share this firepower with approximately equal destructive capability. just two squares on the chart (300 raegatons) represent enough firepower to destroy all the large and medium size cities in the world. (Physics and Society, 12, No. 4, 12, October 1983.)

beings suffered oppression and injustice. If today's choices appear to be suffering without nuclear war or suffering as the result of nuclear war, they make more plain to us the road of negotiation and understanding in attempts to alleviate the causes of war.

Perhaps the most subtle of all modern dilemmas is the argument for deterrence in the nuclear age. If "our enemy" (note the tacit assumption that we should deal with millions of human beings as "our enemies") builds up a nuclear arsenal, then we must build up a larger nuclear arsenal in response so that our enemy will be deterred from using his weapons against us out of fear of reprisal. Such deterrence may indeed appear to work for a while as a matter of practical politics, as

A Christian commitment to non-violence should never be interpreted to mean that Christians are passively to endure injustice, evil, and unrighteousness around them.

Now there are several possiblities. The first possibility is that the threat of deterrence is genuine. If our enemy should launch a first strike attack against us, we would promptly push the button that would send our answering strike against him. Can we really maintain that it would be an act of consistent Christian responsibility to push the button that releases a torrent of nuclear destruction upon another country's people so that they may suffer the same fate as we are about to? Knowing that decimation of our own nation is a certainty, is it then conceivable that an act of Christian motivation would exact vengeance by pushing the fatal button? At this point deterrence has become irrelevant. There will be no future need for deterrence at all. Can anyone imagine Jesus responding by pushing the button in this case?

A second possibility is that we say that we are building up a deterrent force but make it perfectly clear that if push comes to shove our own ethical principles will make it impossible for us to push the button. This, of course, is no deterrence at all. To possess a nuclear arsenal while declaring that we will never use it is a foolish exercise.

A third possibility is for us to build up a deterrent nuclear arsenal with no intention of ever using it for ethical reasons, but we pretend that we will use it if we have to. We are bluffing, and we hope that our bluff will not be called. We exonerate ourselves ethically because we never intend to use the nuclear weapons we are stockpiling, and if we can gain

deterrence by pretending to have plans for their use, who is hurt? But such a bluff stands little chance of being undetected, and what kind of a witness do we bear by pretending to do something that we will not ultimately do because we believe it to be evil?

Such dilemmas as these, however, are really only exercises in sophistry. In each case we have supposed that an extensive nuclear arsenal will be built up, and that the goal will be to have at least as large, and if possible a larger arsenal than "our enemy." The very existence of such an arsenal represents a potential evil. Our dealing with the sophistry of the above dilemmas is based on the assumption that we will maintain control of this arsenal after we have built it up, that we will be and remain in charge of its ultimate disposition for as long as it exists.

Finally we must reckon with what is not stored up because the nuclear arsenal is prepared. We must consider the waste in human genius, human creativity, human resources, and scientific and technological know-how. How many people were not fed? How many children died or led lives psychologically twisted and damaged? How much energy research, or medical research was never done? How many people, gifted with the ability to tackle a wide range of problems essential to the welfare of humanity, have had their abilities aborted by a lifelong career in the development, testing, and stockpiling of nuclear weapons?

SummaryChristians uniformly claim that longsuffering and active love is the only ultimate response to evil in this world, the only truly redemptive and life-changing response, the response that is given to us in the teachings and example of Jesus Himself. And yet many, if not most, Christians are able to hold to some view of war that enables them to justify participation by Christians in war and support of war by Christians. This internal contradiction in the lives of God's people constitutes one of the most challenging of all ethical dilemmas.

It appears that there are only three responses to the life, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ as far as a Christian's response to evil through physical violence is concerned. One is that Jesus was simply wrong about this, as He is supposed to be wrong about other things as well (e.g., the events of the future and the time of His own return), and that His ideals can be treated with respect but cannot be responsibly put into practice here and now. A second is that we misunderstand Jesus if we argue that His teachings and example demand Christians to refrain from physical violence in response to evil; what He taught and did were unique examples of ideals that we should strive to put into practice but to expect them to actually work in a sinful world is foolish utopianism, not worthy of responsible Christian living. Instead of taking Jesus' teaching and example at face value, we must interpret them in the light of other passages such as Romans 13 which justify the use of physical violence by organized society and hence by Christians as participants in that organized society. The third is that Jesus was right, that He said what He meant, that He lived what He said, and that our difficulty is that His life and example are so incredible we cannot bring ourselves to accept their simplicity-much as we have difficulty with the simplicity of the Gospel of salvation by grace since it so completely appears to contradict our everyday experience.

To accept this third option does not mean that a Christian in commitment to physical non-violence, is passive Q ineffective in a sinful world. Quite the contrary, the Christian is called to exercise the power of God in confronting every manifestation of evil with divine creativity, including being willing to suffer in defense of others, once again using Jesus' example in Gethsemane and Calvary as our examples.

It is not true that one who rejects Christian participation in an army-or the rightful place of warfare in a sinful world, must logically also reject the activity of a police force. There is scriptural support for the existence and respect of a police force in Romans 13 and I Peter 2, although neither these passages nor the historical record give us unambiguous guidance as to the propriety for Christian participation. The latter must once again be decided on whether the police force acts to restrain evildoers with a minimum of physical violence' Some situations may permit Christian participation while others may not.

The conditions of just War theory are beneficial in that they do set limits to how far any Christian might legitimately stretch the teachings of Jesus to justify a violent response to evil. The burden of deciding is certainly not easy and crucial crises of the spirit may well be expected in the future as they have been encountered in the past. What is clear, however, is that no war fought in recent years or likely to be fought in the future satisfies the criteria of just War theory. The realization that we live in a nuclear age only emphasizes this further and removes any claim that physical violence involving nuclear war could ever be construed as living out the teachings and example of Jesus.

The issue is a fundamental and serious one. Every aspect of

the central Christian message testifies to the fact that a

physically violent response to evil (and I do not overlook the

fact or the danger of other kinds of violence as well) can only

compound evil in the world and not overcome it. Jesus died

defenseless and alone on the cross in order that the good news

of His Gospel might be preached and lived. When His

disciples sought to fight to defend Him, He forbade them.

The victory of the Resurrection was the open proclamation

that longsuffering love had triumphed over evil. To deny this

central core of the Gospel runs the danger of calling into the

question the very integrity of Jesus Christ and of the whole set

of relationships and truths that Christians treasure in Him.

For to this you have been called, because Christ also suffered for you,

leaving you an example, that you should follow in his steps. He

committed no sin; no guile was found on his lips. When he was reviled,

he did not revile in return; when he suffered, he did not threaten; but

he trusted to him who judges justly. He himself bore our sins in his

body on the tree, that we might die to sin and live to righteousness.

(I Peter 2.21-24)

REFERENCES

1R.H. Bube, "Optimism and Pessimism: Science and Eschatology," Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 15, 215 (1972)

2 D.A. Dombrowski, "Pacifism, a Thorn in the Side of Christiantiy," Christian Scholar's Review 9,337 (1990)

3L. Morris, The Gospel According to Saint Luke, Tyndale New Testament Commentaries, InterVarsitv Press, Downers Grove, Illinois (1974), p. 310.

4H.O.J. Brown, "A Preventive War Response," in War: Four Christian Views, R.G. Clouse, ed.. InterVarsity Press: Downers Grove, Illinois (1981), p. 114.

5R. H. Bube. "The Christian and the Terrorist, The Church Herald 35, No. 9, 14(19781

6D- Aukerman, The Scandal of Defenselessness, Sojourners April (1980), p. 25.

7See, for example, J. McDowell and J. Gilchrist, The Islam Debate, Here's Life Pub- San Bernardino, Catifornia (1983)

8R. Taylor and R. Sider, "Fighting Fire with Water," Sojourners April (1983), pL 14

9Cited in Reference 8.11R.H. Bube, "The Foolish Alternative," The Church Herald 26, No. 23, 18 (1969)

12H.O.J. Brown, Reference 4, p. 112.15When Would War with the Soviet Union Be justified?" Eternity June (1980).