Science

in Christian Perspective

Science

in Christian Perspective Science

in Christian Perspective

Science

in Christian Perspective

The Human Explorer-A Tri-level Communication Model

W. Jim Neidhardt

Physics Department

New Jersey Institute of Technology

Newark, New Jersey 07102

From: JASA 33 (September 1981): 183-185.

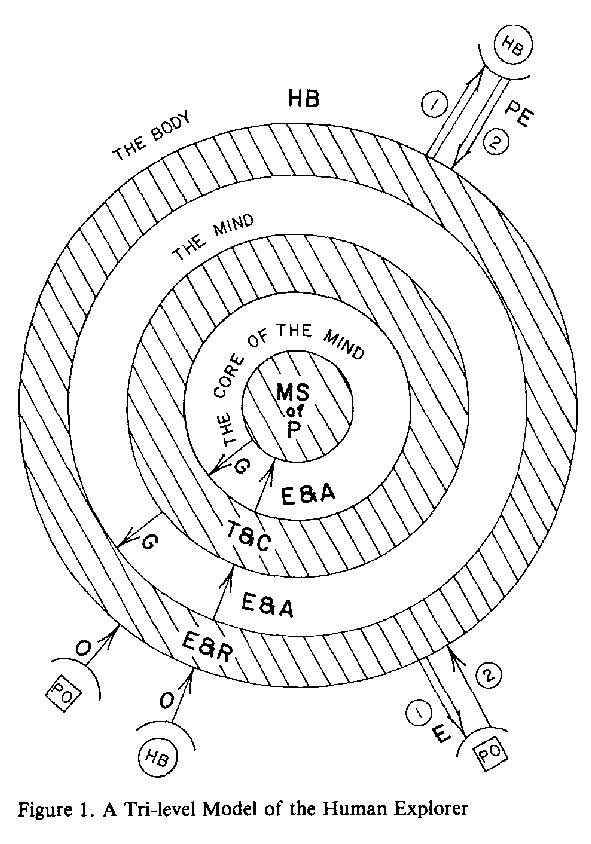

What is the true nature of personal existence? Is not a key component of personal existence at its best a continual exploration of one's environment, such exploration taking place in the context of communication with other human beings and with physical reality? A person is thus seen as an explorer, whatever the subject area may be (philosophy, science, art, and religion being particular areas of investigation) who proceeds on his or her quest by means of communication processes. The essence of a person's activity as a communicator is captured in a three-leveled model of human nature illustrated in Figure 1, the outer level being the human body and the inner two levels the essential structure of mental activity.

Human MindAt this point it should be stressed that modern understanding of human evolution of man as a physico-chemical system does not undercut the appropriateness of the category mind as a unique level of reality needed to

completely describe man. The human body, in particular the central nervous system and brain, serves as the necessary embodiment of the mind; when one reaches the level of material complexity of a human brain new properties and activities of matter emerge which cannot be subsumed or described in terms of languages and concepts appropriate to lower levels of material complexity. This is what emerge means in a evolutionary context. At a lower level of complexity the wetness of water as a new property appears when hydrogen and oxygen atoms combine to form the higher level of complexity, water; wetness is a new property not characteristic of the component parts, hydrogen and oxygen atoms.

In the same manner the emergent quality of mind appears, This quality is less obvious than that of "wetness of water from hydrogen and oxygen, or of the first living cell from its constituent macromolecules, because in this instance, and this one alone, in man we are reflecting on that emergent quality which makes reflection on any-thing possible at all."1 These uniquely human activities of the brain may be properly termed mental; they are reflected in man's self-conscious behavior, in his use of the word "I" of himself in ways which are, in many ways, semantically peculiar, and in his ability to transcend his own environment. Pascal pointed out that ".-U bodies, the firmaments, the stars, the earth and its kingdoms, are not equal to the lowest mind, for the mind knows all these and itself; and these bodies nothing."2 This assertion of the reality of conscious and self-conscious activities is not dependent on any particular philosophy of the relation of the entity called "mind" to one called "body". There are human activities and experiences that take place that may be labelled mental activity and what is referred to is uniquely and characteristically human.

"These include, inter alia, the activities referred to when we say men are capable of rational action, of making moral choices, of choosing between beliefs, of forming personal affections; that men are 'persons' in the sense that each is a bearer of rights, is unique and is someone with whom we can imagine ourselves changing places; that men explore the environment and formulate concepts to organize what they find; they are creative and worship and pray; and they have consciously to come to terms with the anticipation of their own individual death."3

As Figure I shows, the outer level of the human explorer may be seen as the person's body with all one's sensory receptors and effectors by which one encounters reality. The body interacts with its environment by means of three basic communication processes: observation, experiment, and personal encounter, as defined in Figure 1. To understand the meaning of the body's activity one

Nomenclature:

HB-A human

being whose exploratory activity can be described

in terms of a three-level structure. E & R-Effectors and receptors

of the body-the level of human physical existence. T &

C-Theories and conjectures about all reality formulated in the

mind-the level of conjectural thought. MS of P-Metasystem of

basic human presuppositions forming the core of all mental structures: the level of inspiration and revelation. PO-Physical object

(including the physical aspects of a human being). O-Observation; a simple, one-way message from a physical object or another

human being. E-An Experiment: (1) Messages which assume the

form of measuring processes directed by human theories and conjectures at external reality. These messages are designed as "questions" expressed through measuring processes. (2) Responses are

specific "answers" (usually quantitative) to the given measurement probes. These responses, guided by one's theories and conjectures about physical reality lead to further measurement probes.

The signals (1) and (2) are not symmetric in the sense that in principle (1) is structured freely by the mind and (2) is structurally determined by the inherent order of the object under investigation. (2)

represents the completion of a feedback loop with respect to the

human communicator; such loops are essential to all true communicative acts. PE-A Personal Encounter: (1) Message from

one person to another consisting of affirmations and questions. (2)

Responses from the other person consisting of both affirmations

and further questions. These affirmations quided by one's theories

and conjectures about the other person lead to further messages.

The messages (1) and (2) are symmetric in the sense of both intrinsically being structured freely by human minds. (2) represents the

completion of a feedback loop with respect to the human communicator; such loops are essential to all true communicative acts.

G-Guides. E & A-Enhances and alters

must use the language of the mind viewed as organized at two

levels. The structure of the outer level of the mind consists of

theories and conjectures about reality which guide and shape the

exploration of reality by the body. This guidance occurs as

follows. Associated with a given mental state are specific physical

states of the brain; these physical states direct (as the brain is part

of the body) the body's receptors and effectors to be appropriately

activated and deactivated. The inner level,. the "core" or "heart"

of the mind consists of the metasystern of truly basic presuppositions without which all human thought and exploration of reality

around us would be impossible. These basic presuppositions guide

the mind in choosing between alternate theories and conjectures

about all existence. Note that in this tri-level model of the human

explorer communication is both "inward" and "outward". The

results of exploration at the level of the body can both enhance and

alter the theories and conjectures that guide exploration; and, in

turn, the resulting success or failure of theories and conjectures

can both enhance and alter basic human presuppositions that

guide theory formulation.

The Two-Level Structure of Mind

Let us examine the two-level structure of the human mind in

more detail. Some would argue that it is unnecessary to invoke the

level of theories and conjectures as providing guidance to observations and experiments; such human activity is completely theory

free. This has been refuted in great detail by N.R. Hanson. He

points out that:

". . The infant and layman can see: they are not blind. But they cannot see what the physicist sees; they are blind to what he sees... To say that Tycho and Kepler, . . . , DeBroglie and Born, Heisenberg and Bohr all make the same observations, but use them differently is too easy. It does not explain controversy in research science. Were there no sense in which they were different observations they could not be used differently. This may perplex some; that researchers do not appreciate data in the same way is a serious matter. It is important to realize, however, that sorting out differences about data, evidence, observation, may require more than simple gesturing at observable objects. It may require a comprehensive reappraisal of one's subject matter. This may be difficult, but it should not obscure the fact that nothing less than this may do . . . There is a sense, then, in which seeing is a 'theoryladen' undertaking. Observation of X is shaped by prior knowledge of X. Another influence on observations rests in the language or notation used to express what we know, and without which there would be little we could recognize as knowledge ... But physical science is not just a systematic exposure of the senses to the world; it is also a way of thinking about the world, a way of forming conceptions. The paradigm observer is not the man who sees and reports what all normal observers see and report, but the man who sees in familiar objects what no one else has been before. . ."4

What guides us in our formulation of theories and conjectures about the nature of other people and physical phenomena? Theory formulation is enhanced and altered by the results of one's contact with all reality, but it is guided by one's basic convictions about the nature of reality. This framework of ultimate presuppositions, or metasystern of basic convictions, may be looked upon as the center or core level of mental activity. Pascal called it the heart; it directs the formulation of all conjectures about people and things. As the totality of human experience bears in upon us it inspires in us basic convictions about reality that guide all that we do. We hold to these ultimate convictions even when immediate conjectures about reality seem to deny their validity. Often these ultimate convictions come to us by being tacitly shared with us when we are members of a community formed by people holding common interests, i.e. the scientific or religious communities as examples. This inspiration

that we receive from encounter with the totality and richness of human experience is responsible for the creation of these basic convictions is us. Such inspiration may be looked upon as God's revelational activity toward mankind through His continual holding all reality in being and through specific actions He has taken in human history as biblically revealed. These basic presuppositions undergird all human though and resulting action; they are held so firmly that we are often unaware of their existence. Such ultimate convictions tacitly guide all our thought processes. To paraphrase Pascal: Faith indeed tells us what the senses and strictly logical thought do not tell, but not the contrary of what they see. It is above them and not contrary to them.

Ultimate Convictions7. Reality is contingent. Concerning presuppositions 6 and 7 it can be pointed out that:

". . There is a very close connection de jure between the Christian belief in a God who is both rational and free and the empirical method of modern science. A world which is created by the Christian God will be both contingent and orderly. It will embody regularities and patterns, since its maker is rational, but the particular regularities and patterns which it will embody cannot be predicted a priori, since He is free; they can only be discovered by examination. The world, as Christian theism conceives it, is thus an ideal field for the application of the scientific method, with its twin techniques of observation and experiment."5

8. Descriptions of nature are inherently simple in terms of structure. It is always possible to find explanations of physical phenomena that look toward a central point of reference, thereby unifying a wide variety of experience by the use of a minimum number of primary concepts and interrelationships. Einstein, referring to his relativity theory, pointed out that this approach is a key motivating factor of science:

"The theory of relativity arose out of efforts to improve with respect to logical economy, the foundations of physics as it existed at the turn of the century ... Our experience hitherto justifies us in believing that nature is the realization of the simplest conceivable mathematical ideas. I am convinced that we can discover by means of purely mathematical constructions the concepts and the laws connecting them with each other. which furnish the key to the understanding of natural phenomena."8

9. To truly communicate with reality, whether other people or things, you must give of yourself in love to the particular task or encounter at hand, Love seeks always to act toward external reality in a spirit of cooperation, empathy, and respect; to properly control external reality without destruction resulting you must always first seek understanding of nature's inner harmonies and then work with these harmonies rather than against them. This conviction of the importance of love to all exploration is inherent in the striking analogy that exists between Bacon's formulation of the principle of inductive observation, and Jesus' disclosure of the basic paradox of the Christian life. Bacon pointed out that "We cannot command nature except by obeying her." and Jesus said "He that loseth his life for my sake will find it."

10. Basic explanations of physical phenomena are truly beautiful in an aesthetic sense, Concerning Einstein's discoveries in physics Yukawa has written:

"He had a sense of beauty which is given to only a few theoretical physicists . . . Simplicity alone may be reached by mere abstraction, while a sense of beauty seems to guide a physicist in the midst of abstract symbols."7

What basic convictions do scientists have about the nature of beauty in science? Two criteria for beauty are suggested in a recent article entitled Beauty and the Quest for Beauty in Science.

The first is the criterion of Francis Bacon:"There is no excellent beauty that hath not some strangeness in the proportion!" (Strangeness, in this context, has the meaning "exceptional to a degree that excites wonderment and surprise.")

The second criterion, as formulated by Heisenberg, is complementary to Bacon's:

"Beauty is the proper conformity of the parts to one another and to the whole."

The article then shows at great length how Einstein's general theory of relativity fulfills the two criteria proposed for scientific beauty.8

ConclusionsThe tri-level model of the human explorer that has been introduced is an attempt to capture the most significant aspects of how human exploration comes about. What has been shown is that the observations, experiments, and personal encounter present in all acts of discovery are not performed in a random or haphazard manner; they are always guided by one's theories or conjectures about external reality. Furthermore, different theories or conjectures about reality are not created through the evaluation of objective data alone but also are formed and molded by a person's deepest convictions about the nature of reality. Personal commitments to the ultimate rationality of all reality, to standards of intellectual and moral integrity, and finally, to criteria of intellectual beauty: all these play a key role in theory formulation. Therefore it is quite possible for two different scientists exploring the same part of reality to collect and evaluate very different sets of data depending on what their guiding theories consider important. The same reality can possess many different levels of explanation, some dependent on others; each level has its own set of categories of explanation and theoretical conjecture. As an example a human being can quite properly be described in terms of concepts appropriate to the level of mental phenomena, the mind, or at the level of physical existence, the body, with mind states being dependent on body states (not necessarily in a one-to-one manner). It is also possible that two different scientists exploring the same part of reality will collect essentially the same data but each will interpret them in a very different way because each is guided by very different theories about the reality being examined.

These different theories have come about because the two scientists have very different ultimate convictions about the structure of reality. On a broader scale the philosopher, the theologian, the scientist, and the artist explore reality by means of equally valid but very different and unique complementary theoretical structures and presuppositions; they each ask very different kinds of questions of reality and receive very different kinds of answers. If a theologian, an artist, and a purely physical scientist observe the same sunset, each will give very different but equally valid complementary descriptions of it.

References1A. R. Peacocke, Science and the Christian Experiment, Oxford University Press, New York, 1971, p. 142.

2 Blaise Pascal, Pensees, The Modern Library, New York, 1941, p. 278.5E.L. Mascall, Christian Theology and Natural Science, The Ronald Press Company, New York, 1956, p. 132.

6Albert Einstein, Out of My Later Years, The Citadel Press, Secaucus, 1977, p. 101. Second quote of Einstein found in Elementary Particles by C.N. Yang, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1962, p. 65.7H. Yukawa, Creativity and Intuition: A Physicist Looks East and West, Kodansha International, Tokyo, 1973.

8S. Chandrasekhar, "Beauty and the quest for beauty in Science", Physics Today, July 1979, Vol. 32, No. 7, pp. 29-30.