Science

in Christian Perspective

Science

in Christian Perspective Science

in Christian Perspective

Science

in Christian Perspective

Astronomical Distances, the Speed of Light,

and the Age of the Universe

David J. Krause

Science Division

Henry Ford Community College

Dearborn, Michigan 48128

From: JASA 33 (December 1981): 235-239.

At the beginning of the 19th century a powerful new argument for the great age of the universe was provided by the convergence of two seemingly unrelated earlier lines of scientific investigation. The first was the discovery that light has a finite, definite velocity. Whether light propagated instantaneously or with an exceedingly high but nevertheless finite velocity was a long debated question. Kepler and Descartes, for example, still supported the concept of instantaneous propagation. However, about 1676 Roemer, through analysis of the eclipse times of the satellites of Jupiter, laid the foundation for the first reasonable estimate of light's velocity, and the discovery of the abberation of starlight by Bradley in 1727 allowed the velocity to be determined as about 192,000 miles per second.1 The second major discovery was that some astronomical objects were located at very great distances from us. Through much of the 18th century many astronomers retained the ancient belief that all stars were located about the same distance away, on the surface of a sphere centered on the solar system, but by 1800 William Herschel, using his famous large telescopes, concluded that some of the stars and nebulous objects he saw were as far as 12 million million million miles. In 1802 he then explicitly combined the finite velocity of light and these great astronomical distances to produce what is perhaps the simplest, most obvious, and most direct evidence that the age of the universe must greatly exceed a few thousand years.

"I shall take notice of an evident consequence attending the result of the computation; which is, that a telescope with a power of penetrating into space, like my 40 feet one, has also, as it may be called, a power of penetrating into time past. To explain this, we must consider that, from the known velocity of light, it may be proved, that when we look at Sirius, the rays which enter the eye cannot have been less than 6 years and 41/2 months coming from that star to the observer. Hence it follows, that when we see an object of the calculated distance at which one of these very remote nebulae may still be perceived, the rays of light which convey its image to the eye, must have been more than nineteen hundred and ten thousand, that is, almost two millions of years on their way; and that, consequently, so many years ago, this object must already have had an existence in the sidereal heavens, in order to send out those rays by which we now perceive it."2

The response of several individuals to this evidence indicates that the implications for a vast age of the universe were clearly understood in the 19th century. For example, Thomas Campbell wrote of a conversation he had with Herschel in 1813:

"Then, speaking of himself, he said, with a modesty of manner which quite overcame me, when taken together with the greatness of the assertion: 'I have lookedfurther into space than ever human being did before me. I have observed stars of which the light, it can be proved, must take two millions of years to reach the earth.' I really and unfeignedly felt at this moment as if I had been conversing with a supernatural intelligence. 'Nay, more,' said he, 'if those distant bodies had ceased to exist two millions of years ago, we should still see them, as the light would travel after the body was gone.3 "

In discussing this astronomical work of Herschel, Alexander von Humboldt observed in 1846:

"Such events or occurrences-reach us as voices of the past.-We penetrate at once into space and time.-It is more than probable that the light of the most distant cosmical bodies offers us the oldest sensible evidence of the existence of matter."4

This astronomical evidence for great age was particularly impressive in that it independently provided confirmation for similar conclusions regarding the age of the earth that were emerging from geological investigations. Writing at the middle of the last century John Pye Smith specifically commented on the convergence of the astronomical and geological evidences as he attempted to formulate a consistent interpretation of Scripture based on the new scientific conclusions.

"But there are two sciences, Astronomy and Geology, which bring us into an acquaintance with facts of amazing grandeur and interest, concerning the Extent and the Antiquity of the created Universe."5

After carefully discussing Herschel's work based on the travel time of light, using several illustrative examples, Smith concluded:

"These views of the antiquity of that vast portion of the Creator's works which Astronomy discloses, may well abate our reluctance to admit the deductions of Geology, concerning the past ages of our planet's existence."6

In succeeding years the concept of an earth and universe of great age became thoroughly integrated into the scientific world view. Refined in this century by the discovery of radioactivity and numerous other dating methods and by the discovery of ever more distant astronomical objects, present scientific evidences are, of course, generally held to be consistent with an age of some 5 billion years for the earth and some 10-20 billion years for the universe as a whole.

Recent Alternative Views"Contrary to popular opinion, the actualfacts of science do correlate better and more directly with a young age for the earth than with the old evolutionary belief that the world must be billions of years in age."7

Similarly, but more specifically, Harold Slusher has written:

"However, the scientific evidence continues to accumulate labelling the huge ages of the universe, the solar system, and the earth as a fable, not a conclusion reached by an adherence to scientific proof. The actual data interpreted i terms of the basic physical laws would seem to point toward a young age for the cosmos . . . The evidence seems to indicate that the alledged 4.5-5xI09-year-old earth ... should be replaced by about 101 years. I believe the cosmos was created at some time between 6 and 10 millenia ago."8

Unfortunately, support for such claims frequently produces analyses whose exact implications are not always clear or of con vincing validity, partly, at least, because the issues are very com plex. The evidence for great age based on the travel time of light k quite direct, however, and involves relatively few basic assumptions. Below I attempt to evaluate the response of some who ad vocate a "short" time scale for the universe to this simple astronomical evidence, and particularly examine the claim that their arguments have a scientific basis.

Reduced to its simplest form, the astronomical argument for the great age of the universe can be expressed by the equation T= D/c where T, the time required for the light from a distant object to reach earth (and, hence, its minimum age) equals D, its distance from earth divided by c, the speed of light. As c is a constant of a 186,000 miles per second, and astronomical evidence indicates even the nearest galaxies are some 1019 miles distant and the these detectable objects some 1023 miles away, it immediately follows that the light from these objects must have been travelled for millions to billions of years in order to get here. For those take the position that the scientific evidence favors an age of a thousand years for the universe, how is the force of this conclusion to be avoided? Possibilities would seem to be few. In the a equation the only way T could be greatly reduced is either if c, speed of light, is much higher than the accepted value or if D, distances of the objects are far smaller than is generally thought. All evidence, however, seems to indicate that c is indeed a constant, and the equality of abberation effects for all astronomical objects further indicates that it has not varied significantly during the various times required for their light to reach us.9 The possibility is that the various stars and galaxies being observed not nearly as far as thought by astronomers. However, in order the light from all objects in the universe to reach the earth since creation some 10,000 years ago, none could, of course, be than 10,000 light-years away. This would require modern distance determination methods to be in error by factors ranging up to a million, which seem unlikely indeed. Slusher, for example, strongly arguing for a 6 to 10 thousand year age for the universe nevertheless in his analysis of astronomical data does not suggest that modern distance estimates are seriously in error, and ap parently accepts the great distances involved as essentially correct.10

What, then, of the original question? How is the astrono

implication of great age to be avoided? Surprisingly, while

technical issues such as radioactive dating, the age of the earth's

magnetic field, and terrestrial cooling have received detailed comment from short-time-scale advocates,

11 the astronomical evidence

based on the travel time of light has received much less attention,

in spite of its clarity and directness. Sometimes the issue is simply

not discussed, even though the context would seem to require it.12

On those occasions when the issue has been faced, however, the

proposed solution, from Whitcomb and Morris in 1961 to Slusher

in 1980, seems to have taken a characteristic form:

The Moon and Spencer Hypothesis"In connection with the time it takes for light to get here from the stars, a very important work was done by Parry Moon of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Domina E. Spencer of the University of Connecticut. This work was published in the Journal of the Optical Society of America, August 1953. This work is significant particularly in the matter of the age of the universe. . . ."13

The "Moon and Spencer hypothesis" has on numerous occasions been cited by those supporting a short time scale for the universe as a possible (and evidently, the only) scientific reason for rejecting the great age implied by the astronomical data.14 This hypothesis will therefore be examined here with particular reference to the reasons it has become a standard reference to those arguing for a "young" universe.

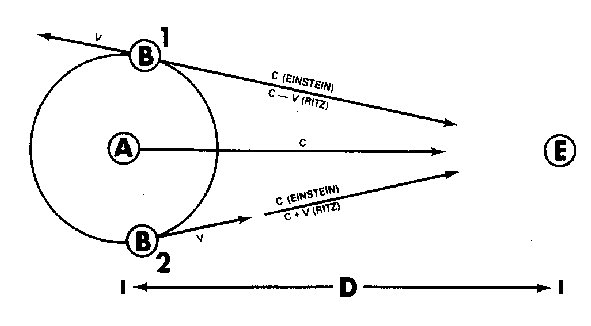

The Moon and Spencer paper of 1953 contains seven parts." The first five constitute a straightforward, detailed analysis of a specific scientific problem, but the last two contain far-reaching, unsupported speculations. The earlier parts analyze an alleged proof of one of the postulates of special relativity. Einstein postulated, in the early years of this century, that the velocity of fight is a constant which, contrary to ordinary velocities, is independent of the motion of the source or of the observer. About the same time Ritz proposed, alternatively, that the velocity of light is constant only with respect to the source (thereby rejecting special relativity), and that its velocity relative to an observer would depend on whether the source is moving toward or away from the observer, as with ordinary velocities. DeSitter suggested that a pair of orbiting stars would resolve the issue. Greatly simplified, the situation would be as in the figure. Star B orbits star

A with a velocity v, being first at point 1, where it is moving away from the earth, E, and then at point 2, where it is moving toward the earth. If Einstein is correct, the light from star B at both positions I and 2 travels toward the earth with velocity c, and we would simply see B orbiting A in a normal manner, with a time lag due to the distance D that the light had to travel. If Ritz is correct, however, the light from point I will travel toward the earth with a velocity slower than c, (c-v), while the light from point 2 would travel faster than c, (with velocity c + v), so that if the stars were far enough away the light from point 2, even though it started toward the earth after that from 1, could actually "catch up" and get to the earth at the same time, raising the possibility that the same star could be seen simultaneously in two different places! A number of other odd effects should also be detectable if the Ritz theory is correct. Since, as DeSitter pointed out, none of these anomalous effects is in fact seen in orbiting stars, this clearly supports Einstein and special relativity.

In considering this issue, Moon and Spencer were able to demonstrate that the visual binary stars which, according to DeSitter, favored Einstein over Ritz do not in reality allow a choice to be made; the predicted effects are too small to be measured. They therefore clearly show that DeSitter's claim of support for special relativity on the basis of the evidence of visual binaries is invalid. Moon and Spencer did demonstrate further, however, that for other classes of stars, particularly the spectroscopic binaries and the Cepheids, the anomalous effects would be detectable by direct observation, and therefore the total lack of such effects in these stars does indeed indicate that Einstein, rather than Ritz, is correct, and that special relativity is supported.

". . the Cepheids provide a proof even more decisive than that given by the spectroscopic binaries, a proof that the velocity of light does not partake of the velocity of the source."16

To this point everything is straightforward. Moon and Spencer have demonstrated a significant historical point, but there are no implications for a short time scale for the universe. Having just provided "a proof", however, they suddenly reverse themselves and ask if there is any way that Ritz might still be right in spite of the evidence just cited that he is not. They then point out that if no star were farther from the earth than about 15 light years, there would not be enough travel time for the anomalous effects to build up to a detectable level, even if the light from opposite sides of the star's orbit was traveling with different velocities, as Ritz suggested. But, they agree, astronomical distances are measured as vastly greater than 15 light years. They therefore make the highly unusual suggestion that there are two kinds of space; I I astronomical space", in which the various stars and galaxies are actually located at the distances indicated by the usual astronomical measuring techniques, and "Reimannian space", through which the light from these objects somehow moves in traveling to the earth.

"The usual distance r employed by astronomers is unchanged as regards material bodies; but for light, it is replaced by the corresponding Riemannian distances. . . . In essence, therefore, the method of this paper leaves astronomical space unchanged but reduces the time required for light to travel from a star to the earth."18

This, then is the hypothesis seized upon by advocates of a "young" universe in order to avoid the implications from astronomy for great age.

Discussion"You can leave the stars at their astronomical locations, in Euclidean space, but the light from these stars can get to us in very small periods of time-at the most 15.71 years."18

Although Slusher has characterized his own work as having "as

little dependence on assumptions and guesswork as possible" and

has stated that "it is tremendously important to keep actual observations separate from speculative

inference" 20

he continues to advocate these hypotheses, which are nothing if not speculative, in

spite of the evidence against them. It seems clear, however, that

they are without basis.

The Apparent Age Hypothesis

Other advocates of a short time scale may well remain equally

unperturbed at the demise of the work of Moon and Spencer.

Whitcomb and Morris, for example, have repeatedly demonstrated their willingness to utilize the "apparent age" hypothesis, the

sole purpose of which is to avoid recognizing the implications of

any scientific evidence for great age, when faced with evidence that

cannot be explained away in any other manner. They argue, in this

case, that the light rays we see never actually came from the objects

in question, but were directly created carrying an "apparent"

earlier history of events which never actually occurred.21 To their

credit, some other supporters of a short time scale have recognized

the difficulties inherent in this concept,22 but Morris has advanced

an even more extreme position, suggesting that some astronomical

bodies may have been visible even before they existed.23 He

evidently sees nothing unscientific or antiscientific about these

conclusions. However, in a somewhat different context, Stanley

Jaki has demonstrated the destructive nature of such reasoning on

any attempt to formulate a consistent Christian and scientific

world view. In one of his monumental studies of the relationship

of science to Christianity he points out that already in the 14th century William of Ockham, in his move toward

nominalism, had

drawn certain conclusions that are remarkably similar to those

Morris and Whitcomb mentioned above. In driving a wedge between faith and reason, Ockharn specifically

divorced the stars from the light by which we see them.

"As Ockham illustrated this all-important point, since the light of the stars and the stars themselves could be conceived as existing independently of one another, reason was powerless to decide whether the light of stars had a real connection with the stars themselves, ...In Ockham's account of the intellect, the light diffusing in the world was not necessarily coherent with the stars, nor did the same light bespeak a universe in which all stars and material units, small and big, were intrinsically interconnected. ...For the purposes of science the starry sky could not have been enveloped in a deeper darkness. ...This was the logic of Ockham, but not the logic of the Bible and of science."24

Rather than representing a major step toward modern science

Jaki believes that Ockham in fact "...not only banished the soul

science, which always implies generalization in terms of univer

he also excised its very heart, the search for causes embedded in

layer beneath the immediately experienced surface,"25 remarks

that perhaps also would apply to those who continue to take refuse,

in an "apparent" universe. Whatever other merits this type of

theorizing might possess, I believe one thing is clear. Any

System

of thought that incorporates such "apparent age" arguments

not claim to be based upon or to be consistent with a scientific

interpretation of the world.

Conclusion

The discovery that light has a finite velocity and that

astronomical bodies are at vast distances from the earth provided

simple, direct evidence that the universe must be very old. Some

those who hold the view that the age of the universe is only a

thousand years have attempted to avoid the force of this evidence

by advocating the Moon and Spencer and the apparent

hypotheses. The first of these is demonstrably invalid, and the sec

ond is inconsistent with a scientific understanding of the world.

Scientific theories are not absolute, not graven in stone.

too change and metamorphose into new and different fo

However, if present evidence, scientifically interpreted, is to be

guide, the great distances of many astronomical objects com

with the finite value for the velocity of light to provide one of

clearest indicators that the age of this universe of which we are

part is to be measured in the many millions and even billions

years.

References

1J.H. Sanders, The Velocity of Light, (New York: Pergamon

Press, 1965), ch. 1.

2The Scientific Papers of Sir William Herschel (London:

Royal Society and the Royal Astronomical Society, 1912),

pp. 51, 213.

3Francis H. Haber, The Age of the World. Moses to

(Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1959), p. 228 from William Beattie, Life and Letters of Thomas

(London, 1849), V-2, p. 234.

4John Pye Smith, On the Relation Between the Holy Scrip

and Some Parts

of

Geological Science, from the fourth

don edition (Philadelphia: Robert E. Peterson, 1850), p.

quoting from Alexander von Humboldt, Cosmos, tr. Mrs.

onel Sabine, (London, 1846), V-1, pp. 145, 496.

5Smith, On the Relation... , p. 11.

6Ibid., p. 254.

7Henry M. Morris, ed., Scientific Creationism (San Diego: Creation-Life Publishers, 1974), p. 160.

8Harold S. Slusher, The Origin of the Universe

(San Diego: Institute for Creation Research, 1978), p. 47, and Age of the

Cosmos

(San Diego: Institute for Creation Research, 1980), p.

74.

9Sky and Telescope,

V-50 (November 1975) p. 298.

10Slusher, Age

of the Cosmos,

ch. VI. Interestingly, Slusher eviddently accepts as valid the use of some distance determination

methods to distances far in excess of any actually measured to

date (p. 32).1

11Harold S. Slusher, Critique of Radiometric Dating,

Thomas G.

Barnes, Origin and Destiny of the Earth's Magnetic Field

(San

Diego: Creation-Life Publishers, 1973), and Harold S. Slusher

and Thomas P. Gamwell, The Age of the Earth

(San Diego: Institute for Creation Research, 1978).

12In The Origin of the Universe,

for example, Slusher extensively

discusses astronomical data he believes indicates a "young"

age for the universe, but never addresses the question of the

travel time of light.

13Shisher, Age of the Cosmos, p.

33. See also John C. Whitcomb,

Jr. and Henry M. Morris, The Genesis Flood (Grand Rapids,

Michigan: Baker Book House, 1961).

141n Age of the Cosmos,

after discussing the work of Moon and

Spencer (p. 37), Slusher makes a rather vague reference to "a

number of other suggested solutions to this problem", but unfortunately provides no further details.

15Parry Moon and Domina Eberle Spencer, "Binary Stars and the

Velocity of Light", Journal of the Optical Society of America

(1953) V-43, pp. 635-41. 1 thank Professor John N. Moore,

Department of Natural Science, Michigan State University, for

bringing this article to my attention.

16Ibid., p. 639.

17Ibid.

18Slusher, Age

of

the Cosmos, p. 37.

19Kenneth Brecher, "Is the Speed of Light Independent of the

Velocity of the Source?", Physical Review Letters (1977) V-39,

pp. 1051-4.

20Shisher, Age of the Cosmos,

ch. 1.

21

Whitcomb and Morris, The Genesis Flood, p. 369. For a historical perspective of the apparent age doctrine, see my paper

"Apparent Age and its Reception in the 19th Century", Journal of the American Scientific Affiliation

(1980) V-32, pp.

146-50.

22For example, Robert E. Kofahl and Kelly L. Segraves, The Creation Explanation (Wheaton: Harold Shaw Publishers, 1975), p.

154.

23Morris, Scientific Creationism, p. 210. Further questions immediately arise. If it is true that all astronomical bodies are surrounded by a "shell" or "sphere" of light, millions of lightyears in extent, which carries the message of apparent events

that never actually occurred, what scientific reason do we have

for believing that these objects "really" exist even today. More

intriguing, what apparent earthly events are being witnessed to

by the light from the earth that is just now reaching distant

galaxies? Do the earth and the sun also have an "apparent

history" extending millions of light-years out into space? What

does this history record?

24Stanley L. Jaki, The Road of Science and the Ways to God,

(Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1978), pp. 41, 2.

25Ibid.