Science

in Christian Perspective

Science

in Christian Perspective Science

in Christian Perspective

Science

in Christian Perspective

2 Figures absent

Communication: The Leaven that Holds the Church and the Scientific

Community Together

W. Jim Neidhardt

Physics Department

New Jersey Institute of Technology

323 High

Street Newark, New Jersey 07102

From: JASA 32

(June1980): 126-128

The theme of communication has always been a central tenet of

Christian theology.

The communication of love between Father, Son, and Holy Spirit existed in the

Christian Trinity before the universe was formed. The properly

functioning church,

as Figure I portrays, is held together by communication linkages. As

you harmoniously

communicate with God and He communicates His purposes to you, you are able to

harmoniously communicate with your Family and other church members

thereby establishing

a working fellowship and a unity of purpose. Note that for a true

unity and fellowship

to develop in the church, all must maintain an ongoing dialogue with

our creator-God.

Remember also that even when we are not making the effort to communicate with

God, God in His love, is always seeking us out for His loving

purposes, even though

we may not be aware of His communicating acts. Lastly, each person thinks and

communicates through his or bet own matrix of personal commitments concerning

the nature of reality; all communication between individuals and God

is filtered

through these matrices. These individual faith matrices are in turn embedded in

the matrix of presuppositions of the general culture (The Metasystem

of culture).

This model of the church and its relationship to God is seen to be strikingly

analogous to the scientific community in its exploratory relationship

to physical

reality, as Figure 2 indicates. Figure 2 views scientific exploration

as continual

communication of scientists between themselves and reality. Michael Polanyi1 sees

science as a model of a free society engaged in a collective

exploration. Communication

between scientists is essential so that each may know what progress others have

made and accordingly may build upon and extend the work of others. Scientific

understanding thereby expands due to such collective, freely

communicating efforts.

Each scientist chooses what particular research path to follow but by constant

communication they all are aware of each other's work; thus

communication between

them has enabled each to utilize the insights of others and avoid unnecessary

duplication. Furthermore constant communication with physical reality

is the only

means by which insight can be gained as to its true law-structure as contrasted

to a priori speculations concerning it. To describe such behavior Polanyi uses

the analogy of a group of people attempting to solve a jigsaw puzzle in a free,

collective effort. Each participant is aware of what the others have

done in fitting

pieces together and he or she moves accordingly. Note that there is a

key presupposition

that all the participants tacitly hold: The jigsaw pieces really fit together

so form a coherent picture. From this model Polanyi draws an

important implication.

Attempts to extensively

Figure1. The Church in Ongoing Communication with Triune God.

plan scientific activity will hinder rather than help scientific progress.

As Polanyi has shown, this communication model of the scientific enterprise can

be extended to answer a key question often asked of the scientific

community:

"How can we confidently speak of science as a systematic body of knowledge

and assume that the degree of reliability and intrinsic interest of each of its

branches can be judged by the same standards of scientific merit? Can

we possibly

be assured that the new contributions will be accepted in all

areas by the same standards of plausibility and be rewarded by the

same standards

of accuracy and originality and interest'?"2

Figure 2. Scientific Exploration as Continual Communication of Scientists

between

Themselves and Reality.

The fact that contributions in science can be evaluated by the

scientific community

as a whole. even comparing the values of topics of marginal interest

in such diverse

fields as astronomy or biology, is due to a principle of mutual

control in which

fields of scientific specialties form chains of overlapping neighborhoods. By

the principle of mutual control one means that scientists keep watch

on each other's

work.

"Each scientist is both subject to criticism by all other scientists and

encouraged by their appreciation of him. This is how the scientific opinion is

formed which enforces scientific standards and regulates the

distribution of professional

opportunities. It is clear that only fellow scientists working in

closely related

fields are competent to exercise direct authority over one another; but their

personal fields will form chains of overlapping neighborhoods

extending over the

entire range of science. It is enough, of course, that the standards

of plausibility

and worthwhileness be equal at every single point at which the sciences overlap

to keep them equal over all. Even those in the most widely separated branches

of science will then rely on one another's results and support one

another against

any laymen seriously challenging their authority. Such mutual control produces

a mediated consensus among scientists even when they cannot

understand more than

a vague outline of one another's subjects."3

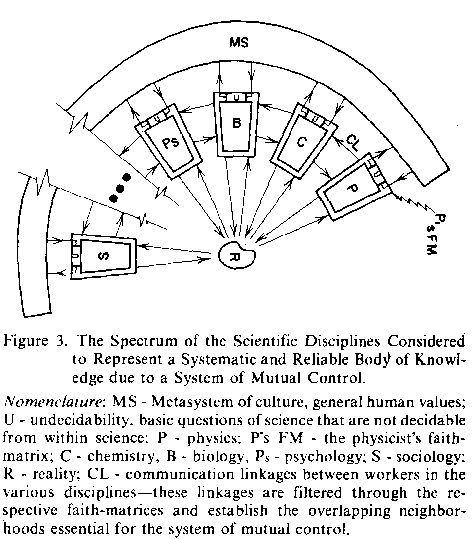

Figure 3 depicts the spectrum of scientific disciplines envisioned by Polanyi.

The chains of overlapping neighborhoods are formed by communication

linkages between

scientists in the different disciplines as the diagram indicates. All

such communication

linkages work through the faith-matrices of the respective individual

scientists

in the differing disciplines. These faith-matrices in turn are

embedded in a wider

matrix of general presuppositions of the metasystem of general culture. Indeed

the whole structure of scientific authority as we have envisioned it

would collapse

if separated from such basic societial trusts as:

(a) Truth can be obtained by free discussion and free inquiry.

"This manner

of settling disputes and establishing consensus is a heritage common

to our general

democratic institutions."4

(b) Human beings have the capacity to discover truth; we can

recognize and share

a rational and universal standard.

A striking analogy exists between the structure of the church with

its relationship

to its object of study and worship the Triune God, and the structure

of the scientific

community with its relationship to its object of study all physical

reality. Indeed

both community structures reflect that which is at the very heart of the nature

of the Triune God, for communicative acts are central to the

relationship between

the three Persons of the one Godhead. At the core of the structure of

both communities

is the concept of communication, both to and from the respective

realities under

investigation or worship and communication between members of the

respective communities.

Of course to study the nature of God requires communication methods and types

of questioning very different from those used in the study of

physical reality.

When we study inert nature we pose our questions in such a way as to manipulate

and deform physical reality so that hidden features are revealed and

new phenomena

observed. When we study the objects of attention in the human sciences we are

faced with a much more open dialogue where we often find our own

motives are probed

by their questions and it is only when openness prevails on both sides of the

encounter that real understanding

through communication results. And when we as church members encounter God, it

is He that always initiates a true dialogue probing the very core of

our rebellious

nature as He sweeps away any attempt on our part to manipulate Him, also by His

very nature as love refusing to manipulate us in any way but always seeking an

open and truthful dialogue from which we may understand the clarity

of His ultimate

love toward all His creation that He continually sustains in being.

To best communicate

with God, we should open our hearts and minds and first listen to His revealing

Word rather than attempting to question manipulatively as when

dealing with inert

nature.

Lastly note that communication with physical reality or the Triune

God presupposes

that she reality we encounter is ultimately rational in its nature

and, secondly,

that we as humans possess means of communication (either experimental

and theoretical

techniques of questioning or intelligible human languages) that are

also rational

in their nature.

The second main idea of the analogy is that for understanding of the Triune God

or physical reality to take place communication is essential between members of

the respective communities. With respect to the church, the Christian

community,

Jesus and Paul both pointed out many times that only when a person is in loving

communication with his or her fellow believers will God accept a

person's worship

and petitions and reveal Himself to that particular person. To put it

in another

way, if a person cannot experience loving communications with his or

her neighbors

he or she is not capable of experiencing communication with God whose

very nature

is love. Communication experiences with imperfect human love prepare a person

to experience communication with perfect divine love. Similarly with respect to

the scientific community, if a scientist isolates himself from the rest of the

scientific community he has become isolated from many creative

sources of rational

understanding; even if the particular scientist is a genius, this

isolation will

eventually deprive him of the insights and techniques necessary to successfully

probe a physical reality that it ultimately rational in structure but

whose rationality

is at an inner level not immediately perceived from the phenomena observed in

direct experience. Thus, both in theology and the other sciences communication

as open dialogue among the respective communities members is essential to even

the most gifted person if he or she is to gain true understanding.

It is instructive to carry this analogy further by comparing the

manner in which

the spectrum of scientific disciplines explore all facets of a

many-sided reality

to the manner in which the spectrum of denominations of the church attempt to

achieve greater understanding of the nature of God and His redemptive

acts toward

His creation. The scientific community makes progress and upholds

universal standards

by maintaining constant communication with physical reality and

between scientists

of the spectrum of neighboring disciplines. As physical reality is manyfaceted

it requires the insights and techniques of many differing points of view (the

different scientific disciplines) to gain understanding of reality as a whole.

In this there is a fundamental unity to all science though it is

composed of many

different subdivisions, Such principles as conservation of energy and

the inevitable

increase of disorder in isolated systems play a vital role in many

different scientific

specialties. The scientific subdivisions maintain progress toward

greater understanding

by preserving open communications between themselves; often a new development

or technique in one field is found to be very useful to workers in other fields

(sometimes quite different). Only by maintaining communication linkages between

fields is this type of useful information flow established.

With respect to the denominations that compose one true Church: a diversity of

viewpoints that are continually exploring and worshipping the many

different aspects

of God can be quite helpful in acquiring greater true understanding. Differing

denominations have grasped differing aspects of the nature of the one God; the

resulting theologies can ideally complement one another in attempting

to describe

the inexhaustible depths of God's nature. But a core of truth can be maintained

and one-sided distorted theologies avoided only if the denominations actively

attempt to understand, test, and utilize the insights of the other

denominations.

Accordingly communication linkages must be actively maintained between members

of the spectrum of neighboring denominations for theological progress

to be made.

(This is analogous to what is done by the scientific community in communicating

across the spectrum of scientific disciplines.) In my opinion, the church as a

whole lags far behind the scientific community in maintaining

communication ties

between neighboring communities (denominations), thereby hindering the growth

of theological understanding. By better establishing and maintaining

such communication

ties greater understanding and true unity of fundamental issues could

be obtained

in the one true Church. Note that in establishing such communication linkages

the individual denominations are in no way committed to yielding

their own distinctive

understandings or agreeing with every thing that another denomination believes;

rather the denominations together will seek to find and preserve the

central core

of Christian belief as C. S. Lewis so forcefully accomplished in his

own work.

References

1Michael Polanyi, The Logic of Liberty, The University of Chicago

Press, Chicago,

1951, pp. 3438.

2Michael Polanyi and Harry Prosch, Meaning, University of Chicago

Press, Chicago,

1975, p. 191.

3M. Polanyi and H. Prosch, ibid., pp. 191-192.

4Richard Gelwick, The Way of Discovery, Oxford University Press, New

York, 1977,

pp. 4546.

128