Science

in Christian Perspective

Science

in Christian Perspective Science

in Christian Perspective

Science

in Christian Perspective

Christianity and Culture II. Incarnation in a Culture

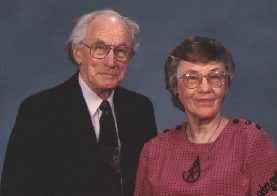

KENNETH L. PIKE

Summer Institute of Linguistics, Inc.

Dallas, Texas 75236

From: JASA 31 (June 1979): 92-96.

Jesus was incarnate in a human body; incarnate in

a human mind; and incarnate in a human specific culture. His beard-cut undoubtedly followed the local custom. His robe

was of local

pattern. His weeping was in local good taste. He walked with sandals;

ate no pork;

discussed local philosophical chestnuts; grew up within a kinship

structure; planed

lumber; and chose to die like a local criminal accused by the

establishment. His

incarnation in body is discussed frequently; His incarnation in

culture, seldom.

kinship

structure; planed

lumber; and chose to die like a local criminal accused by the

establishment. His

incarnation in body is discussed frequently; His incarnation in

culture, seldom.

He was courteous by their cultural criteria. He followed-with rare

exceptions-the

grass-roots local rule system. And His speech was incarnate in a

local, low prestige

dialect-that of Galileenot that of Jerusalem. And when Peter was

accused of being

one of "his crowd," it was this local dialect which marked him off.

I once wrote a little poem about it.

Thy Speech Betrayeth Thee

How can I tell who you are?

Every idle word marks your track with private scent.

Every vowel, every tone, every gives a trace of your origin and your bent from afar.

Clues to cronies and your works are wrapped up in accent chirps

Little Bird!

Don't you try to fly-

just deny and squawk and cry

(and be prepared to die Little Bird).

Character will out

just as softly

and as loudly

as you shout

or pout.

In Mark My Words (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1971:107-08)

Cultural Ideals Fulfilled in Christ

Every culture has ideals which are positive (not merely a conscience

against the

bad). And God, as I hear Him speak to us in the Word, is in sympathy with these

ideals, supports them; and we know that ultimately He is the source

of these good

things, since "every good endowment and every perfect gift"

(James 1:17

RSV) is from the Father of lights-whether it comes by way of a

genetic endowment,

or from a cultural one. Good hopes, good dreams of helpful life, good

aims incarnate

in a culture have this as their point of origin.

For this reason, therefore, we conclude that Christ can meet, on

their own terms,

the good ideals of every culture. He can fulfill these dreams first in Himself,

incarnating them as fulfilled in Himself, and eventually He can help the good

dreams to he incarnated in us and, then, in our resurrection bodies when we are

conformed to His image. And meanwhile, he can show men of all cultures that it

is possible to approach toward their own ideals better by His strength and by

His will infused in them. He thus fulfills their need, their moral

longing, rather

than tossing away this genuine but incomplete moral knowledge.

The Christian as a Model

Their wistfulness to be good, according to criteria which are related to God's

absolute character, is involved in drawing men to him. As part of the process,

men are supposed to see us, and wish to imitate usand are supposed to find in

us an early approximation of that character of God which they

wistfully wish for

in themselves. With Paul we must he able to say, as he said repeatedly (II Thess. 3:7, 3:9, Phil, 3:17, I

Cor. 4:16),

"imitate me,"

as I imitate Christ, except for that residual mess which still binds

us all. "We

are on the way," we must he able to say, "come along!" By this

criterion, they must he able to want to follow-not in our academies, not in our

politics, not in our role or jobs in society, but in our path toward

being conformed

to Him.

Cultural Blocks to a Message

This cannot he seen readily across some cultural barriers. The signs

of character

can he culturally misread unless there is cultural incarnation by us into their

system; i.e. unless we translate our actions into patterns which they

can understand.

But here are two problems:

First, we are still sinners. People can see that. Fortunately,

however, by-standers

watching a stutterer can see in some mysterious fashion that the

"real"

message does not include the stutter part; and in a profession, plus an attempt

with partial success, people can to some extent differentiate the

moral stuttering

from the effort and from the general direction, and start on the same

narrow path.

Second, however, some cultural differences can temporarily block a

message. Attempts

at friendliness may appear as being ton forward. Or cultural bits may trigger

wrong understanding, or may block understanding. For example, in a

simple instance

where life or death but no moral issue was involved, I heard that two

of my colleagues

of the Summer Institute of Linguistics were walking at night in

northern Australia,

where there are deadly snakes. One of the aborigines suddenly shouted

out a warning:

"Jump east!"-but which was east? There they had no word-no

translation

directly-for "left" or "right," they went by the

compass (though

having no compass!). "Doctor," they would on occasion say, "my

south ear hurts;" or "Take the north cookie, it is nicer." (The

universe may be more stable this way I suppose-it does not "revolve"

with us when we turn! But for those of us who have not been taught directions

this way by our culture, their warning may be missed.)

More puzzling was the reaction of Chief Tariri (whom I have mentioned before)

when two S.I.L. women first were introduced to him. He thought that

they "laughed

in his face" and "tried to throw him to the ground." (Dangerous

practices when dealing with a man used to taking heads!) Why? Cultural miscues,

undoubtedly. My hunch: the women had been taught that they should be friendly

to people in Latin America, to smile and to shake hands. But this was a jungle

Indian culture, not Latin. And in some Indian areas a greeting may

include a bow

plus the lightest of touching of the hands-where a "warm handshake"

involving unexpectedly heavy pumping could threaten to throw one off

balance-either

physically or socially. Furthermore, the kind of smile which is appropriate may

be culturally conditioned. In Australia, for example, when greeting someone the

lips often remain closed at the sides, and the cheeks crease close to the lips;

when I have pointed out to Australian women that I could often guess

whether pictures

for ads in the magazines were taken there or in the U.S.A., because

of the broad

smile on the face of the American women, they replied: "Yes, it looks like

a toothpaste advertisement." If such

There are universals of kindness and of courtesy which need translation-incarnation-into (emically patterned) cultural molds.

had been the case with Ta 'in when meeting the two friendly, smiling

North American

girls for the first time, he could have taken a "friendly smile" for

a guffaw at his expense. Messages to he quickly and easily effective,

then, must

be culturally incarnate.

Universals of the Good Neighbor

Fortunately, there is something universal about friendship, something

genetically

transmitted which is deeper than culture, something which underlies

kindly human

relations in all cultures. And the evidences of individual kindness gradually

filter across cultural and language barriers. Kindness is a

universally recognized

quality, given time; a kindly person speaking the language badly will

eventually

communicate more of the love of God than a harsh person who has the

proper consonants.

But just as in Part I we pointed out that there are universals of

conscience which

have variable manifestations, so here there are universals of kindness and of

courtesy which need translation-incarnation-into (emically patterned) cultural

molds.

By the parable of the good Samaritan (Luke 10:2537) Jesus captured

such a generalization

about the universality of kindness. Philosophical argument could

dispute definitions

of it; His parable incarnated it in an irresistalble situation, This

was a function

of His parables; they forced attention to the incarnation of principles, where

perception of their force could not he interrupted by sophisticated

verbal blockade.

The good neighbor is also the kind that a man wants to have when he

himself must

leave home, and wants someone near there who will take care of his

wife, his children,

and his riches. He wants that man to be honest. Yet I have seen the wish fail.

My chief translation helper of the Mixtec New Testament, leaving home to work

with me for a while, had some goods stolen by the close friend who was to watch

them.

The Anti-Neighbor

Thus far 1 have been implying that in some sense there is a universal

good neighbor,

a universal ideal man (with etic variability around local emic structures). But

one major difficulty with the suggestion most be met before we can feel at all

comfortable with it, or use it as a basis for further encouragement as we seek

to enter into other cultures, If we were to ask a person what he wants to be,

he might answer in a way that suggests that he does not at all want

to be kindly,

or to be a good neighbor. It may be that he wants to dooiinatc others. This is

not the ideal neighbor-it is the ideal tyrant. And in a certain sense this is

indeed the wish of all fallen men, i.e., of all of us. Even the disciples felt

this way, and had to be taught that it was undesirable: "You know that the

rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their great men

exercise authority

over them. It shall not be so among you" (Matt. 20:25-26). Among

the Gentiles,

these kings are called

"benefactors" by the dominated ones (Luke 22:25). (How startled I was

some years ago to land in Trujillo's capitol, only to be given an

official pamphlet

lauding him as "benefactor"-what an unexpected confirmation of human

nature in literal terms!)

The Christian church is not exempt from such heady dreams. Diotrephes liked to

"put himself first" (III John 9, 10), did not acknowledge

the authority

of John, and put men out of the church who did not follow his wish.

But Paul taught

us that to be like Christ we must not seek equality with Greatness (Phil. 2:6).

And the urge for power through wealth, or status through position, or pride of

place through role, or through dress, or high friendships, or smooth words, may

trap us all, win or lose, succeed or fail. The particular individual

emic structure

of power-search may vary, but the underlying bad dream may persist.

How can we reconcile this (had) desire for domination with the claim that there

is a good ideal in all cultures? We must admit that there are clashing ideals:

the clash between the ideal of the good neighbor versus the ideal of

the man who

for pride wants bigger farms at someone else's expense. My conviction: all men

(with a few possible exceptions) have an underlying wistfulness to he

good which

may he deliberately overridden and ignored under the competing desire

for dominance.

(Even Judas, at the end, "repented and brought hack the thirty pieces of

silver . . . saying 'I have sinned'" (Matt. 27:3, 4).

Hidden Wistfulness Towards Goodness

I think of this hidden wistfulness, this ignored wish, as something

like the green

in the trees in Ann Arbor, before the maples have turned red, To turn

the leaves

red takes a chemical change. To turn them yellow, you have only to

have the green

chlorophyll decay; then the yellow which was already there becomes visible. I

think that the moral structure is perhaps something like that. I have been told

that a dying man, knowing he is dying, who confesses to a crime, is

almost certainly

telling the truth about it. Why? My hunch is that his wistfulness to

be good had

been overridden by the lust for safety and power. This wistfulness to be decent

to his friends-rather than letting them be its jail for his crime is

overwhelmed

by the "chlorophyll of power madness." But when the power

madness cannot

work, when he is dying, and can no longer hope for power or find gain

in safety,

when he can no longer be put into jail, the wistfulness to be good

shows up, and

he may confess to that which has damaged his friend.

Christ as Competitive with Contrastive Cultural Ideals

But we return now to the claim that Jesus can compete with and best

any man with

his own weapons. This applies whether it relates to competition

towards dominance,

or competition towards meeting ideals of neighborliness. If it is via dominance

that one wishes to issue a challenge, one can hear the message to Senacharib:

"The virgin daughter of Zion-she wags her head behind you ...

whom you have

mocked . . . have You not heard, that I determined it long ago . . . I will put

my hook in your nose, and my bridle in your month, and I will turn you hack on

the way by which you came" (II Kings 19:20-22); here we see that God

refuses to allow evil forces, in the long run, to win by dominating tactics. If

the social ideal is meekness or pacifism, however, Jesus shows

through competitively

as the meek one who "opened not his mouth" (Isa. 53:7) in

threatening,

under the killing attack. Societies differ in their degree of aggressiveness or

meekness. But in each instance, in some sense Christ is The Competing

One relative

to the good-neighbor ideals of that culture or to their negative

dominating "anti"

ideals.

This holds, whether it refers to small ethnic communities, or to very

large ones.

Thus, Ruth Benedict a generation or more ago (in Patterns of Culture,

[19341 1946

Pelican Books, New York), emphasized that the Zuni "value sobriety and in

offensiveness above all other virtues" (54), so that the fact "that

white parents use [whipping] in punishment is a matter for unending

amazement"

to them (63); and "The ideal man in Zuni is a person of dignity

and affability

who has never fried to lead," and "Even in contests of

skill like their

foot races, if a man wins habitually he is debarred from

running" (90).

On the other hand, on the northwest coast of America, where the

"potlatch"

or give-away is standard practice, the "object of all Kwakiutl enterprise

was to show oneself superior to one's rivals . . . . It found

expression in uncensored

self-glorification and ridicule of all comers" (175); their "picture

of the ideal man" (185) was in terms of contests to shame rivals, e.g., by

giving away more property in conspicuous waste (174) but with controls against

overdoing, lest one impoverish ones folks, (which was "phrased as a moral

tabu" (180) ), or by murder of the owner of prerogatives, taking "his

name, his dances, and his crests" (194); but this kind of rivalry "is

notoriously wasteful . . . . It is a tyranny ... it can never be

satisfied"

(228). A hymn "of self-glorification" (177) could be extensive (e.g.

175-77), naming one's names:

I am Yaqatlenlis, I am Cloudy, and also Sweid; I am great Only One, and . . . I am Great Inviter. Therefore I feel like laughing at what the lower chiefs say, for they try in vain to down me by talking against my name . . . (176).

And in such a culture as the Kwakiutl we seem to have

institutionalized the "anti-idealneighbor"

of Matt. 20: 25-28, to whom, in competition, Jesus might refer to

himself as the

"Ancient of Days" on His throne (Dan. 7:13), not a mere

upstart. (There

can be seen a good component here, of a "tax" which in part

distributes

or equalizes wealth, but it is the pride component that I have

focused on.) However,

the One with the "name which is above every name" (Phil. 2:9) prefers

to meet this competition by refusing to "count equality with God a thing

to be grasped" (Phil. 2:6) and, in a curious "wrestling

reversal",

to win by taking the form of a servant. He can show Himself as

potentially incarnate

in all such cultures; and can in that sense (if we allow it) work through our

personality development to show potential or actual incarnation of fulfillment

of these goals. We in our turn should be living patterns of success

in character

structure, pointing to the possibility-in-embryo of reaching ideals that others

have longed for but find themselves unable to reach by themselves.

Here the wistfulness

to follow us should be a pointer to following the Lord.

Just a year ago and in a larger cultural setting Josif

Ton (in "The Socialist Quest for the New Man," Christianity Today 20, No. 3, 6-9, Mar. 26, 1976) helped us to appreciate

the underlying

ideal man of Marxist thought: the concept of the "New Man"

(7a) as introduced

for the future "Communist society which would be established as a result

of the revolution" (7a); they thought that "since a man is only the

product of his environment, one needs only to create a social system founded on

justice and honor to produce a man of noble character, an honest,

upright man"

(7b); they had a "sincere, incensed desire to rid the working

masses of exploitation"

(7a). But "There are indications Lenin realized shortly after

the revolution

that his hope in the spontaneous appearance of the new man in socialism was not

being fulfilled . , . corruption and dishonesty in the socialist administration

became a serious deficiency" (71)). As one Party secretary, a

teacher, told

Ton: "1 am sent in to teach them to he noble and honorable . . ,

to the point

of self-sacrifice ... [to] tell only the truth, and live a morally

pure life. But

they lack motivation for goodness" (Sa). Arid the initiators of

the movement

felt that at the start, the revolution for its actions required

"a desperate

man, a hitter man without any hope in an after life,

without scruples, one who 'knew' that God does not exist to punish (or reward

him)" (61)-7a). Then, the changed economic, political, social environment

was supposed to produce the new man, with new character, automatically-but some

current Marxists now see clearly "that socialist man's character has not

changed. 1-lc has remained [in general-not for all] as he was in the capitalist

society: an egoist, full of vice, and devoid of uprightness" (7a). But as

for people like Ton, "God chose us to follow him from within socialism .

. . . The divine task of the evangelical Christian living in a

socialist country

is to lead such a correct and beautiful life that he both

demonstrates aria convinces

this society that he is the new man which socialism seeks" (91)).

And so, once more, we see that part of God's plan is for a kind of

cultural incarnation

by us into a culture where at some phase-not all of it-the goodneighbor ideal

is wistfully known, even when overcolored by the "chlorophyll" of the

power wish.

Incarnation in Language

Now we return to incarnation into a local language, as Jesus used the dialect

of Galilee. Jesus emptied Himself of the range of communication accessible to

the Word itself. Presumably, He babbled as a babe, such that "increasing

in favor" (Luke 2:52) with His parents would have been in part

through their

delight at His language growth. He learned more than just sounds: He adopted a

system of sounds-an emic system, with contrasts of kinds of

consonants, a limited

set of vowels in syllabic patterns. He learned a grammatical structure, and the

patterns of story telling normal to that culture. He learned the

vocabulary, organized

into a system of taxonomic structural fields specific to that culture. All of

these patterns are human -in one sense in part

"man-made"-in that each

culture may change, add, or drop words in accordance with its

immediate interests.

Each culture has a vocabulary sufficient, I think, to talk of

anything which interested

Unconscious cultural arrogance is perhaps often expressed more directly through one's disinterest in another's language than through any other cultural expression.

its grandparents-and gaps in vocabulary are temporary,

filled in by invention within the culture (as for kodak),

or by borrowing (as for chocolate from Spanish in turn borrowed from

Aztec.) And

this freedom, I feel, is one which is God-designed, God-blessed, from way back

when God told Adam to name the animals-and from there on He

"played the game"

by man's rules: "and [God] brought [the animals] to the man to see what he

would call them; and whatever the man called every living creature,

that was its

name" (Gen. 2:19). That is, God, from the beginning, not only allowed man

to develop his emic taxonomic language struture, but Hintself chose

to work within

man's emic language system in His relation to man. That is, the incarnation of

thought into man's language is not new to God; the need for it in the

bodily incarnation

of Christ did not catch heaven by surprise. It was part of the

original package.

And now He calls on us in turn, to speak the language of the people we wish to

help, insofar as in us lies. It is efficient, friendly; and it contributes to

the dignity of man as individual man. Refusal to do so, when one

could have done

so (granted that one could not fault a person for simultaneously learning-sayten

languages in his immediate environment such as in a boarding school for various

tribesmen) is an affront to that person's worth, as he may react to him.

Unconscious cultural arrogance is perhaps often expressed more directly through

one's disinterest in another's language than through any other

cultural expression.

All the burden of intellectual effort to cross the communication

barrier is loaded

without consideration onto those who appear "inferior" as

they struggle

with the load to cross that barrier. Kindness to one's neighbor would take that

burden on one's self and let the neighbor have the advantage of

freedom of expression,

while we (who because of cultural history, which is none of our

doing, otherwise

pride ourselves on presumed competence or cultural superiority) even

out the load

of communication from large to small culture.

But what are some of these cultural patterns of language, known to

the linguist,

but less known to others? What kind of range of emic structures is

available currently

to man, and clamoring for our effort to try to enter into them?

In pronunciation, those of us from an English environment find

"tones"

hard to speak, and even harder to analyze into emic systems; I myself put many

years into this effort, in analysis first, and in teaching others to

do the same

kind of thing, second.

In the grammar of the inside of words, suffix sets may be very different from

those we are accustomed to.

In the syntax of stories, the order in which the story must he told (in many of

the languages of the island of New Guinea, for example), may be controlled by

time sequence much more than in English, so that the telling

order and the happening order must in general be kept

the same. The result: one cannot say John ate his supper after he

came home; but

must say: John came home, then ate his supper. It may be difficult or

impossible

to find in such a language words to translate easily after, before-or

if, while,

but, because, since, therefore; and the translated order may need to

conform more

closely to the original happening order of the story than to the order in which

the story was told.

Illustrations of such problems-and many more-can

be found in the new text by me and Evelyn G. Pike (Grammatical Analysis, Summer

Institute of Linguistics Publication in Linguistics No. 53, 1977).

Here, however,

I am not trying to show this detail, but to emphasize one point: It is the will

of God, demonstrated in language at creation and at the birth of Christ into a

specific language area, that we should follow the local patterns of

communication,

finding the emie structure of individuals or cultures, insofar as it

is crossculturally

or morally appropriate.