Science

in Christian Perspective

Science

in Christian Perspective Science

in Christian Perspective

Science

in Christian Perspective

Faith, the Unrecognized Partner

of Science and Religion

W. JIM NEIDHARDT

Department of Physics

Newark College of Engineering Newark, New Jersey 07102

From: JASA 26 (September 1974): 89-95

What Is Faith?

The notion of faith1 as a legitimate component of all human understanding has

varied widely through the ages. The following spectrum of definitions

and thoughts

concerning faith makes this abundantly clear:

1. A schoolboy's definition of faith-"Faith is when you believe something

that you know isn't true!"

2. T. H. Huxley3 on faith-"Blind faith is the one unpardonable sin,"

Does it necessarily follow that faith in general should therefore

come under suspicion?

Cannot unbelief as well be blind?

3. David Hume4, the dour and skeptical Scotsman, in his lighter

moments acknowledged

the necessity of having 'a kind of firm and solid feeling." Is this not a

possible definition of faith?

4. Hebrews 11:1-"Now faith is the assurance of things hoped for,

the conviction

of things not seen." Biblically, faith is thus taken neither in

an exclusively

religious sense, much less in specific reference to faith in Christ as Redeemer

and Lord, but very generally as an "assurance" and

"proving"

of objects and concepts which

escape our perception because they do not yet exist or because they

are not immediately

apparent to our senses.5

5. The noted physical chemist and philosopher, Michael Polanyi, has

pointed out

that no one can become a scientist unless he presumes the scientific doctrine

and method to he fundamentally sound and that their ultimate premises

can be unquestioningly

accepted. Only by an unlimited commitment and trust to these premises

can he develop

a sense of scientific values and acquire the skill of scientific enquiry. This

is the way of acquiring knowledge which the Christian Church Fathers described

as fides quaerens intellectum, "to believe in order to know."

Ignoring Huxley's and the schoolboy's judgment as somewhat

short-sighted, we see

that faith can be defined as an act of trusting, of holding to convictions when

the evidence for such commitment is not immediately apparent. It

should be noted

that faith is not blind, nor does it arise out of a vacuum. Faith

stems from man's

previous experience; salvation faith from

Faith is illumination by which a truly rational understanding can begin.

specific historical events (seen through the eyes of faith as God revealing Himself

in history), more general faith from man's contact with reality

through personal

contact with others and experience of order in nature, etc. Faith, however, is

much more than a mere extrapolation of past experience, for it interprets such

experience and holds to convictions which cannot he reduced to mere inductions

from scientific experience. The conviction that a scientific theory

must possess

a rational beauty and symmetry in a unifying sense is a good example.

Faith: A Component of All Human Understanding

How can faith be a necessary component of scientific as well as

religious experience?

Let us first clearly understand that faith does not provide the data

of empirical

knowledge; faith rather plays its role in seeking to find a keystone

idea, a pattern

that will fit and explain the data. Science does not consist merely

of the collecting

of data; we must recognize what is truly coherent in what we observe,

which observations

are truly significant. Such recognition is intimately related to having faith

in the soundness of some key idea or pattern. Once faith in a key

pattern is established,

reason then takes over and develops a more ordered picture, looking

for possible

faults and finally conceiving, of experiments to further test the

theory. Faith7,

to paraphrase St. Augustine, is not a trusting in unprovable truths which can

he disregarded as a rational picture develops; it is, rather,

illumination (which

guides one in seeing a pattern) by which a truly rational

understanding can begin.

The scientific enterprise is no exception to the universality of

Augustine's insight.

A scientist cannot begin his task of deciphering the puzzle of a very complex

physical world without an unconditional and complete trust or

conviction in certain

basic premises that undergird all scientific effort. In essence he must possess

a firm faith that nature is intelligible, that an underlying unique

and necessary

order exists, that there is an ultimate simplicity and inter-connectedness to

the laws of nature, that underlying symmetries exist in the physical

world, that

nature behaves in the same way whether observed or not, that a direct, correct

correspondence exists between events of the universe and his

sensory-brain responses,

that his own senses and memory are trustworthy, and finally that his

fellow workers

do and report their work honestly. To doubt or engage in endless questioning of

such points is to abandon the whole purpose of scientific pursuit.

Faith coupled

with observation and deduction, not merely observation and deduction,

is required

for progress in science.

Let me stress that the scientist's glimpse of the simplicity and

inter-connectedness

of the laws of nature, while being far wider than the layman's, is by no means

exhaustive. The condition of the scientist and the man of religion are in this

respect the same. Religious faith stems from its own evidences, exactly as that

of the scientist; it is not a blind faith. Yet as numerous as

religious evidences

are they do not form a complete exhaustive set. "Those

evidences, like the evidences of science, are rather a prompting toward espousing propositions that

imply unconditional affirmation and absolute commitment."8 It is through

such commitment that the man of science grasps the simplicity and order present

in nature and through a similar commitment that the man of religion grasps the

transcendent dimension of God. Michael Polanyi's description of

reality is a strikingly

fitting example of these last thoughts:

...reality is something that attracts our attention by clues which

harass and beguile

our minds into getting ever closer to it, and which, since it owes

this attractive

power to its independent existence can always manifest itself in

still unexpected

ways. If we have grasped a true and deepseated. aspect of reality,

then its future

manifestations will be unexpected confirmations of our present knowledge of it.

It is because of our anticipation of such hidden truths that

scientific knowledge

is accepted, and it is their presence in the body of accepted science

that keeps

it alive and at work in our minds. This is how accepted science serves as the

promise of all further pursuit of scientific inquiry. The efforts of perception

are induced by a craving to make out what it is we are seeing before us. They

respond to the conviction that we can make sense of experience because it hangs

together in itself. Scientific inquiry is motivated likewise by a

craving to understand

things. Such an endeavor can go on only if sustained by hope, the

hope of making

contact with the hidden pattern of things. By speaking of science as

a reasonable

and successful enterprise, I confirm and share this hope.9

Specific Examples

It would be helpful at this point to give some specific examples that testify

to the validity of faith being a necessary component of scientific endeavor. It

should be understood that I have picked out a few key cases; the

history of science

provides an almost inexhaustible number of illustrative cases for the

basic thesis.

1. Faith in the orderliness and simplicity of nature is truly

required to contribute

in a period of scientific revolution where the foundations of

existing understanding

are overturned by new evidence and new theoretical interpretations.

a) Max Planck terminated the classical era of physics by his

introduction of the

quantum of energy. The classical assumption of the continuity of

nature was shown

to be invalid. One had to look for order in a completely new way.

Planck's testimony

as to how the scientist proceeds in his investigation of nature is

illuminating:

The man who handles a bulk of results obtained from an experimental

process must

have an imaginative picture of the law he is pursuing. He must embody this in

an imaginary hypothesis. The reasoning faculties alone will not help him toward

such a step, for no order can emerge from that chaos of elements unless there

is the constructive quality of mind which builds up the order by a process of

elimination and choice. Again and again the imaginary plan on which

one attempts

to build up that order breaks down and then we must try another. This

imaginative

vision and faith in the ultimate success are indispensable. The pure

rationalist

has no place here.10

b) A. Einstein11 in the creation of his relativity theory

rejected the notion

that space and time are absolute. He defined them in terms of reference to the

frame of the observer. Einstein abandoned absolute space and time, but he did

not therefore view the simplicity and order of nature as merely constructs of the human mind (this is how

idealist philosophers wrongly interpreted Einstein as making the laws of nature

subjective). He held rather to the strong conviction that the basic

laws of nature

are always and everywhere the

same, regardless of the frame of reference in which they are

observed. This conviction

led him to the development of his revolutionary theory.

c) The current state of elementary particle physics has been aptly

called an "infernal

race". With new "particles" being discovered all the

time physicists

still persist in searching for order in this "maze". A

strong conviction

that order exists is an absolute necessity to make progress in this

rapidly changing

field. One central motivating factor is the strong faith of physicists in the

universal validity of key conservation laws. An example from the early history

of particle

physics shows this clearly. The existence of that unusual elementary particle,

the neutrino, was postulated in ordered that certain nuclear reactions maintain

the conservation of energy, momentum and spin. For some time, the

only empirical

evidence for the neutrino's

existence was that these reactions would otherwise negate the

conservation principles.

Even today, the additional empirical evidence we have for the neutrino is quite

different from observations of other elementary particles; it cannot

be observed

in the same ways as these others (electrons, positrons, mesons, etc.). There is

good evidence it can never be seen in the sense that other particles are seen.

Yet neutrinos are today accepted as a component of real nature. Why? To a large

degree, the physicist's faith in a fully lawful cosmos compels such acceptance.12

d) The Medieval picture of the universe was overthrown by Copernicus

when he proposed

a suncentered planetary model in contrast to the earlier earth-centered model

of Ptolemy. The earth-centered system was really in keeping with common sense

observations; furthermore, even if the detailed motions were complex, it made

accurate predictions. Copernicus' strong faith that planetary motions "are

simple" led him to develop his sun-centered theory which violated ordinary

sense observations.

e) Newton,13 in formulating his system of dynamics, brought together

the results

of many earlier workers, as Galileo and Kepler, for example. His

great contribution

was to see a fundamental pattern to these results that had not been noticed or

deeply appreciated before. He was strongly motivated by a basic faith that the

laws of motion are truly universal in scope; i.e., an apple falls to the earth

in the same way that the "moon" falls to the earth, and

that these laws

are mathematically simple, i.e., an inverse, integer, power law of

gravitational

attraction. Such premises were considered to be rather speculative by

many natural

philosophers of the day.

2. Faith in the interconnectedness and symmetry of nature has played a role in

the scientific venture.

a) Faraday, all of his life, searched for a connection between electromagnetic

and gravitational forces. He never gave up hope of finding such a connection.14

b) Maxwell pondered over the fact that a changing magnetic field

creates an electric

field. From symmetry considerations he was motivated to work out the

consequences

of assuming that a changing electric field creates a magnetic field.

He was thus

led to discover

a valid law of nature that led to the prediction of electromagnetic waves.15 In

a similar vein, Faraday was deeply impressed by the experiments of Ampere which

showed that electric currents create magnetic fields. This motivated

him to search

for possible ways in which a magnetic field would create electric currents. His

faith in the possibility of finding "symmetrical" effects in nature

led eventually to his discovery of the law of magnetic induction.16

c) P.A.M. Dirac, the brilliant theorist who successfully merged quantum theory

with relativity, predicting both the existences of positive electrons

(positrons)

and electron spin, has testified to his motivating faith that scientific theory

should be beautiful (simple, symmetric-balanced and possessing harmony):

Yet if we believe in the unity of physics, we should believe that the

same basic

ideas universally apply to all fields of physics. Should we then not

use the equations

of motion in high energy as well as low energy physics? I say we

should. A theory

with mathematical beauty is more likely to be correct than an ugly

one that fits

some experimental data (of the moment) 17

3. The very fact that mathematical systems formulated by the human

mind for sheer

intellectual pleasure have later proved remarkably applicable to an

accurate description

of nature is a great surprise.

As nature is certainly not itself a product of the human mind, the

correspondence

between the mathematical system and the structure of physical reality

is not something

that would have been anticipated in advance. A strong faith that such

correspondences

indeed exist was and is central to the motivation of scientists as they attempt

to understand the complexities of nature. To list but a few examples

of this remarkable

correspondence; the mathematical system of secondorder differential equations

coupled with

To express trust and to act on that trust, to act by faith is not contrary to true rationality.

the inverse square law was later found by Newton to describe

precisely the motion

of masses (and physicists found it later to be applicable to charged particles

as well); the abstract four-dimensional geometry of Riemann was later found by

Einstein to be applicable in describing the motion of bodies in each

others' gravity

(the correspondence was all or nothing-ten equations of motion fit the only one

allowable Riemannian tensor); and, as a final example, the infinite dimensional

abstract Vector space developed by Hilbert with its use of imaginary

numbers was

later found by the pioneers of modern physics to be amazingly

applicable in describing

the quantum nature of both light and matter. Eugene P. Wigner who

formulated these

concepts in a paper, The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in

the Natural

Sciences, concludes with words that are embedded in faith:

The miracle of the appropriateness of the language of mathematics for

the formulation

of the laws of nature is a wonderful gift which we neither understand

nor deserve.

We should be grateful for it and hope that it will remain valid in

future research

and that it will extend, for better or for worse, to our pleasure even though

perhaps also to our bafflement, to wide branches of learning.18

Conclusions

A deep cleavage exists today between the scientific and religious communities,

between scientists and humanists in general. The goals, methods, and problems

of one group are considered irrelevant, of no interest and significance by the

other. Communication between the two groups is at times almost

completely lacking.

One remedy, suggested by C. P. Snow, is that compulsory courses in science be

a requirement at all educational levels. This can be of some help but without

a strong personal motivation, the average nonscientist will easily become lost

in a "maze of facts" resulting from the scientific

knowledge explosion.

Following Jaki, I would suggest that both motivation and true

comprehension would

be greatly enhanced if one looked in detail at the foundations of

both the scientific

and humanist quests. The history of science, past and present, shows that both

the sciences and the humanities have at their center some common

mental attitudes.

One of them, perhaps the most significant, is man's dependence, as he

creatively

seeks to understand all of reality, on his "firm and solid feelings,"

on his faith.19 Faith is a valid component of all human

knowledge, scientific

as well as religious.

Biblically man plays a unique role in creation for he reflects God's

nature, being

made in His image. The Bible portrays God not as an abstract idea or a force,

but as both infinite and personal: Jesus Christ, the God-Man,

stressed the ultimate

uniqueness and significance of personality, of personal relationships based on

absolute and unconditional trust and commitment, on faith of men toward God and

themselves. Jesus stressed that a personal faith is essential to a

true relationship

to God and He praised those who responded in faith without complete

factual details.20

St. Paul continued Christ's message, pointing to Him as the personal

creator and

sustainer of all reality, who calls us to commitment to Him as our Savior and

Lord. Personal response by faith in God is central to Christian

teaching and part

of that teaching is St. Paul's observation that God's presence can be

seen in all He has created, both in the inner nature of man and in external

reality.21

Is not the meaning of St. Paul's insight that God, the author of all order, who

calls us to a full and complete knowledge of Him by personal

commitment, has structured

reality in such a way that personal response and commitment, or more

simply put,

faith, is required by man to gain an understanding of all existence, temporal

and transcendent? Indeed, is not man's capacity to have faith a part

of his uniqueness

that comes from man reflecting the nature of the triune God?

A Biblical aspect of man's nature, necessary for gaining knowledge of God and other people, is also required to gain knowledge of a purely scientific nature as well.

The intellectual mood of our age has presented to us the distortion that faith

is the height of irrationality. Science has been portrayed as a cold,

analytical

discipline devoid of faith or metaphysical content; human and spiritual values

cherished as unique are now claimed to be reducible to

physical-chemical explanations.

It is my belief that the dissatisfaction of many of our young for the

scientific

professions (as indicated by dropping enrollments in these fields),

stems partly

from a rejection of an image of science that is deterministic and impersonal.

These young people ask: How can the same man say that order as expressed in the

countless mathematical invariances of the physicist exists, and yet all we can

know in the moral realm is disorder? Unsatisfied by a caricature of

science which

is devoid of all personal passion, some of our brightest youth have adopted an

extreme form of existentialism in which feeling alone is meaningful

and rational

analysis of no significance.

Christians have also reacted to this downgrading of the validity of

faith in human

experience. Some have reacted by completely compartmentalizing their

perspectives

of the spiritual and natural orders. Others, perhaps repelled by the

very radical

nature of the Christian solution to life's dilemma have tried to

build a 'Christianity'

without the necessity of faith. Such attempts, to my mind, are reactions to a

very faulty picture of faith. Faith correctly viewed is that

illumination by which

true rationality begins, as has been seen through history by men the caliber of

St. Augustine, Pascal, Kuyper, Polanyi, and Jaki.

To express trust and to act on that trust, to act by faith is not contrary to

true rationality. Remember that faith consists not in what can be

proved by results.

Rather faith precedes results, faith motivates us toward results. We trust our

husband or wife always to have our best interests at heart. We trust that the

many long and difficult hours spent attempting to get a finicky piece

of scientific

apparatus to yield complex and often puzzling data will eventually lead to the

universal in scope. We trust that the language and concepts of

mathematics created

originally for sheer intellectual pleasure will be applicable to the

description

of specific physical phenomena. Can we also not learn to trust the One who made us in His image, the God whose very

trustworthiness

guarantees the existence of laws in all of His creation which are

both dependable

and discoverable human effort? True rationality is to consider all

the evidence.

Can we not learn to truly trust the Jesus Christ revealed in all the

Scriptures,

the author of all rationality, the God-Man who seeks us out for fellowship with

Him, a fellowship of service and freedom, not a life of bondage to

self? As servants

of Christ, we have a clear responsibility for developing a world view in which

faith plays an integral role. Only such a world-view can do full justice to the

great richness, complexity, and order present in all reality which is far wider

and comprehensive than we can imagine. Contrary to the critical

attitude of some,

faith is an inherent part of all human endeavor and as such is not destructive

to sense experiences and rational thought but a helpmate to both as

seen so well

by the pioneering Christian and scientist Blaise Pascal;

Faith indeed tells what the senses do not tell, but not the contrary

of what they

see. It is above them and not contrary to them.23

REFERENCES

1The author is greatly indebted to the pioneering work on the

validity of faith-experience

of Abraham Kuyper, Michael Polanyi, and Stanley L. Jaki. The insights into the

nature of human experience of Blaise Pascal and St. Augustine have

been of great

help and a strong motivation to me in developing the perspective presented in

this paper. Key references are:

Abraham Kuyper, Principles of Sacred Theology, Wm. B. Eerdman's Pub. Co., Grand

Rapids, 1968.

Michael Polanyi a. Science, Faith and Society, The University of Chicago Press,

Chicago, 1966; b. Personal Knowledge, Harper Torchbooks, New York, 1964; and c.

Knowing and Being (Marjorie Green-editor), The University of Chicago

Press, Chicago,

1969.

Stanley L. Jaki a. The Relevance of Physics, The University

of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1966; b. "The Role of Faith

in Physics," Zygon. vol. 2 No, 2, June 1967. pp. 187-202.

2Jaki,

ibid. (b),

p. 188.

3jaki, ibid. (b), p. 188.

4Jaki, ibid. (b), p. 188.

5Kuyper, op. cit.,

pp. 125-146.

6Polanyi, op. cit. (a), pp. 15, 45.

7Alan

Richardson, Christian

Apologetics, Harber Brothers, New York, 1947. A central theme of the

book is St.

Augustine's approach to epistomology.

8Jaki, op. cit. (b), p. 199.

9Polanyi, op. cit. (c), pp. 119-120.

10Jaki, op. cit. (a), p. 353.

11Jaki, op.

cit. (b), p. 189.

The net result of "warping" of the faith-matrix is that communication on all levels of human experience is transformed into some form of manipulation.

12Henry Margenau, Open Vistas, Yale University Press, New Haven,

1961, pp. 181-182.

131. Bernard Cohen, The Birth of a New Physics, Doubleday & Company, Inc.,

New York, 1960.

l4Faraday, Maxwell, and Kelvin, D.K.B. MacDonald, Doubleday &

Company, Inc.,

New York, 1974.

l5MacDonald, ibid.

16MacDonald, ibid.

17P.A.M, Dirac, "Can Equations of Motion be used in High Energy

Physics,"

Physics Today, April 1970, p. 29.

18Eugene P. Wigner, "The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the

Natural Sciences," Communications in Applied Mathematics, vol. 13, No. 1,

1960. William G. Pollard, Man an a Spaceship, The Claremont College

Press, California,

1967, pp. 44-51; Science and Faith-Twin Mysteries, Thomas Nelson

Inc., New York,

1970, pp. 8286.

19Jaki, op. cit. (b), pp. 199-200.

20The risen Christ's dialogue with Thomas in John 21:24-29;

Revised Standard Version of the Holy Bible.

21Romans 1:19-20. The King James's Translation of the Holy Bible

brings out clearly

that God has revealed Himself to men both in the structure of their

inner nature

(their consciousness) and the structure of all created physical reality.

221 Corinthians 1:17-18. Revised Standard Version of the

Holy Bible.

23Blaise Pascal, Pensees and the Provincial Letters, The Modern Library, New York (1941), p. 93.

APPENDIX: A COMMUNICATION MODEL

OF HUMAN UNDERSTANDING

It is mainly due to M. Polanyi that we owe the

rediscovery

in modern times of the role of faith as a component of all human experience. In

his significant book, Personal Knowledge, he clearly established that science

as well as other forms of knowledge comes about through a matrix of

personal trust

and commitment, i.e., a faith structure. Polanyi came to this conclusion by good

scientific methodology if science is thought of in its broadest context. What

he did was to examine carefully and comprehensively by means of the available

historical record, both the individual and collective aspects of

scientific activity

leading to the formulation of new scientific theories and discoveries. He was

careful not to neglect evidence of the many personal facets of the scientists

involved that

had a role to play in the creative discovery process. He evaluated

all this evidence

retroductively seeking a pattern that would successfully explain how

discoveries

are really made, not merely how they are reported in the impersonal form of a

completed scientific manuscript. Recognition by Polanyi that

scientists work "through"

a faith or commitment framework provided the clue to the pattern that explains

how scientific discoveries actually came about. Polanyi did not acknowledge the

wider context of his work with respect to JudeoChristian understanding; what he

has actually shown by applying sound scientific methodology to the

whole of scientific

experience is that a Biblical aspect of man's nature, necessary for

gaining knowledge

of God and other people, is also required in order to gain knowledge

of a purely

scientific nature as well. This aspect, which is man's reliance on faith in all

human activity, is part of the image of God reflected in man. Polanyi

has provided

scholarly evidence for the Biblical perspective that man bears the

image of God.

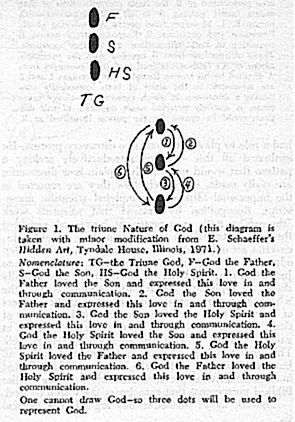

Indeed, as F. Schaeffer has argued, the Biblical

portrayal of the nature of the triune God is one in which there are and always

were love and communication. As Figure 1 illustrates, there are three persons,

Father, Son, and Holy Spirit within the nature of the one God. Between each of

the three persons of the one God there is and always has been a

reciprocal relationship

of love which is expressed in and through communication. Even before

the created

Order had a beginning, love and communication always were. It is

these attributes

that express themselves in the nature of man as bearing the image of God; and

these attributes consititute man's uniqueness with respect to the rest of the

created Order. Any such act of communication, whether it be on the

level of personal

encounter or on the level of a person seeking to understand physical

reality (this

act may be looked upon as a form of communication), as Polanyi among others has

shown, is embedded in a matrix of personal trust and commitment,

i.e., a faith-structure.

A communication model of human understanding on all reality-levels in

which faith

plays a vital role

should therefore serve as a useful guide in understanding how the whole person

seeks knowledge. It is a model which is fully compatible with both the Biblical

perspective and an open-minded scientific perspective. It is, as an

example, fully

compatible with a behaviorist model of human personality taken as one aspect of

the whole person. Its specific insight is that it stresses all communication as

taking place through a channel or matrix of faith. This faith-matrix serves as

a grid, a filter, and a telescope in:

a. motivating the search,

b. focusing on areas of significance,

c. reducing the noise-to-information ratio by selecting out unrelated

areas,

d. seeking relations between different personal traits, conceptual constructs,

etc.

In order more fully to understand any act of human communication

(whether on the

level of person to person or the level of a person seeking

understanding of physical

reality), one should first examine the actual content of the

faith-matrix in which

the particular act of communication is embedded. One should clearly ascertain

what a person (or group of persons) actually believes to be true and holds as

presuppositions (perhaps deeply buried in his or her thinking so that he or she

would no longer recognize them) during the communicative act. These

basic presuppositions

inherent

to any human communication come to be believed as the whole person encounters

experience in its totality. As such, they cannot be "proved," but are

yet truly rational for they are genuine personal responses to the totality and

richness of the flow of human experience. Such personal responses are neither

subjective or objective. "In so far as the personal submits to

requirements

acknowledged by itself as independent of itself, it is not subjective; but in

so far as it is an action guided by individual passions, it is not

objective either.

It transcends the disjunction between subjective and objective (M.

Polanyi, Personal Knowledge, Harper Torchbook, 1964, p. 300)."

If this model of communication is correct it provides a fundamental

insight into

the ills of modem society. The channel for acts of communication, the

faith-matrix,

has become "warped". This "warping" occurs because of modem

man's passion to take as a basic presupposition that only one level of reality

is truly significant and must therefore provide the ultimate explanation of all

human experience. Those committed to scientism brand man as only a

complex machine;

truly self-giving love in personal encounter is therefore only an accumulation

of stimuli-response mechanisms. In a similar manner truly moral acts of men are

explained away. The historical evidence that many and varied human

societies have

expressed conern

for justice and freedom is brushed aside. The modern mystic, on the other

hand, overreacts to such claims of scientism by seeing only deeply subjective

experiences as meaningful; from these all other experiences must be explained.

To the mystic, rational analysis that can be duplicated by others is

of no significance.

In these cases and others, the net result of such "warping"

of the faith-matrix

is that communication on all levels of human experience is

transformed into some

form of manipulation. Basic presuppositions must stem from man's encounter with

the totality of his experience; denial of certain aspects of many dimensioned

reality results in badly distorted vision.

Lastly, the changing perspective of anthropological theory concerning

the nature

of valid criteria for distinguishing manlike from animal behavior lends further

credence to this model of truly human understanding being based in

communication.

The older criteria for

human behavior were rooted in the capability of a creature to use

natural objects

as tools and to remake natural objects so that they were transformed into more

sophisticated tools. Newer anthropological theories formulate

criteria for human

behavior in terms of the ability to communicate concepts requiring

symbolic representation

from one creature to another. Man's uniqueness has shifted from his tool-making

ability to his symbol-making and symbol communicating ability.

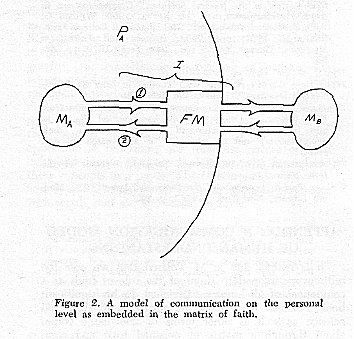

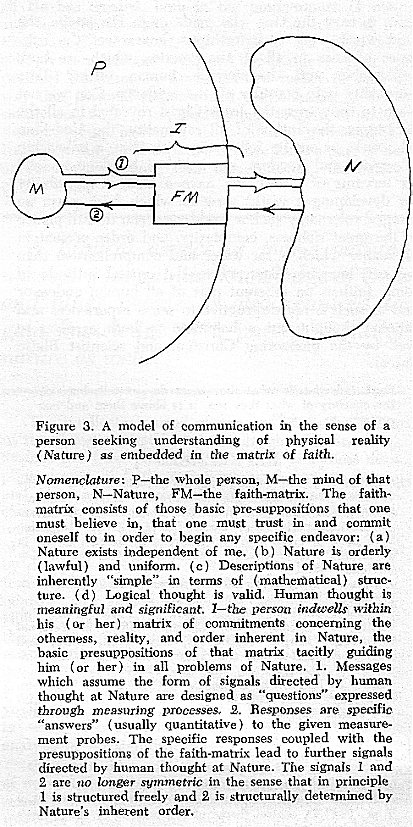

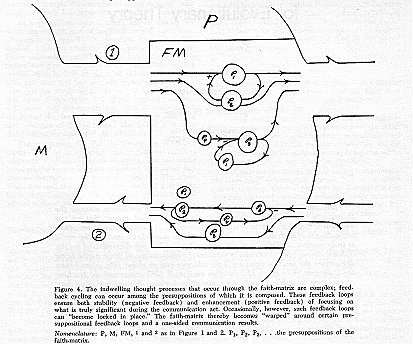

The model is shown in diagram form. Figure 2 illustrates a model of

communication

on the personal level as embedded in the matrix of faith. Figure 3 illustrates

a model of communication in the sense of a person seeking

understanding of physical

reality as embedded in the matrix of faith. Figure 4 is an attempt to

convey some

idea of the complex manner in which communication is channeled

through the presuppositions

to which a knower is tacitly committed.