Science

in Christian Perspective

Science

in Christian Perspective Science

in Christian Perspective

Science

in Christian Perspective

Motivation *

JOHN C. SINCLAIR**

From: JASA 12

(September 1960): 81-85.

The function of the brain can be illustrated by the

gratifying experience we all enjoy three times a day at our meals. The sight,

smell, and taste of food stimulate our brains and we are motivated to eat. If

the nose is clogged up so that the odors do not

*Talk presented at the Fourteenth Annual Convention of the American Scientific Affiliation, June, 1959, Chicago, Illinois.

** Mr. Sinclair is a zoologist at the UCLA Medical School, Los Angeles. He is completing work toward a Doctor of Philosophy degree.

stimulate

our olfactory nerves, the food will be unappetizing and "tasteless."

The pleasure we derive from eating then, is dependent upon the electrical

messages sent along our sense receptors to the brain. So the rewards of eating,

except perhaps for a rise in blood sugar, are entirely incidental to the

function they perform of providing nourishment for the body.

When the stomach becomes distended with food and exhaustion of digestive organs supervenes, the brain ceases to be stimulated by food and eating is inhibited and may even become punishing. But the fine,balance between the excitation of food and the inhibition from the digestive organs is dramatically changed when dessert is served. We suddenly discover that we can eat some more after all!

The balance between excitation and inhibition within the brain in motivated behavior can be inferred by recordings from it or by stimulating it artificially. A greater response from the pre-pyriform cortex -of a cat can be evoked by a fish odor if the cat is hungry.' Rats which have been chronically implanted with electrodes in the brain can be induced to learn a maze, shuttle back and forth between two levers, and even cross a grid charged with electricity, in order to receive a stimulus through these electrodes.2

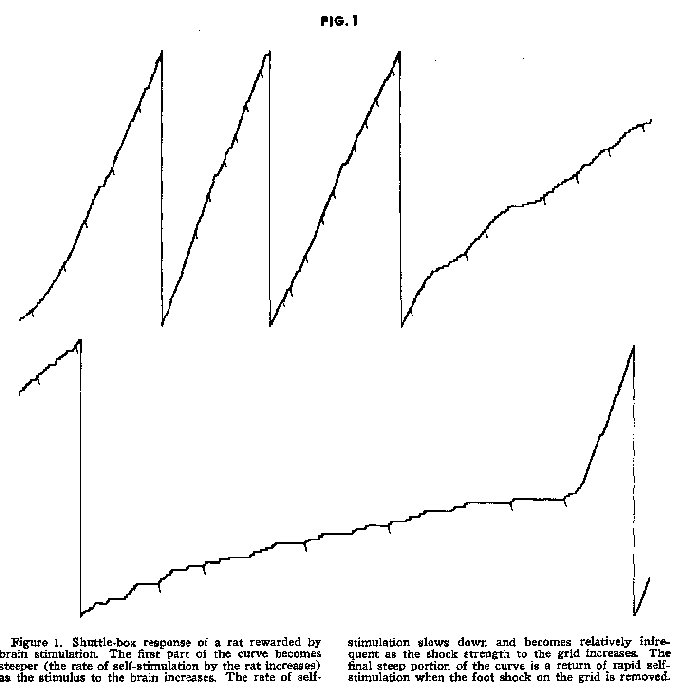

Figure I shows the response of a rat implanted in the hypothalamus. After pushing a lever three times at one end of a grid the animal must cross to the other end and push an identical lever for three more stimuli to the brain. A stepping relay requires the rat to shuttle back and forth after each three stimuli if it is to receive more of them. One vertical scale represents about 200 grid crossings. The horizontal distance represents two hours, one hour for each part. The increasing steepness of the line, or the response rate, in the first part of the record is correlated with the increasing strength of the stimulus received, from 30 to 90 micro-amps of 0.3 sec. duration. A.C. current of about 0.5 volts. Thus the response rate is proportional to the strength of the rewarding stimulus, just as the amount of food we eat is pruportional to how appetizing it is. The gradual slowing up of the response is proportional to the increasing streng1h of shocking current on the grid. It was necessary to raise the foot shock to 780 micro-amps to slow him down to this low rate. At the end of the run with no shock, the rate returns to approximately its initial level so the animal is not being satiated by self-stimulation. It is reasonable to suppose that the shock is inhibiting the self-stimulation behavior similar to the way a distended stomach inhibits eating.3

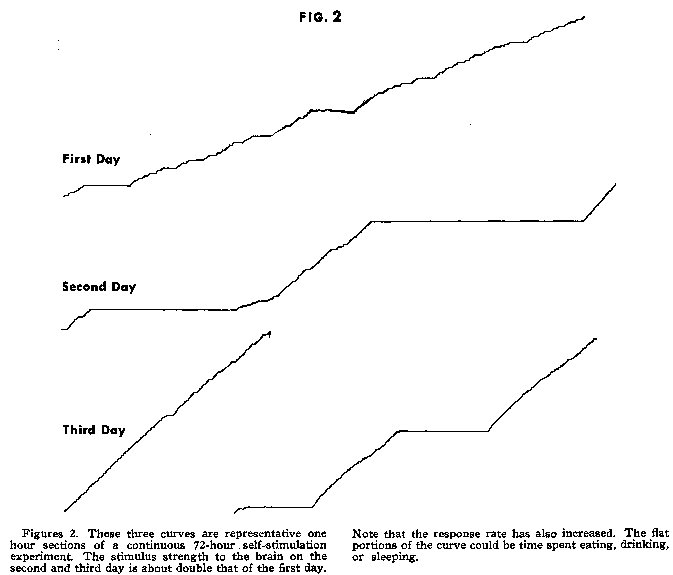

The three tracings of Figure 2 are representative portions of a continuous 72 hour record of a rat permitted day and night access to self-stimulation. The animal has food and water available. The breaks in the curve probably represent cat naps. The second day the stimulus strength was about doubled. It is evident that the rate -has also increased. I show this record to illustrate how well integrated self-stimulation is with normal behavior, that is, with eating, drinking, and sleeping.

We can conclude from these examples that the brain must be stimulated if there is to be motivated behavior, and that the response is determined by the extent to which this behavior stimulates some parts of the brain and avoids the stimulation of other parts.

The desire to place sperm in a vagina is incidental to a fertilized ovum---though this is -the normal result of it. So, gratification of hunger and thirst, that is, the stimulation of specific areas of the brain by odors and tastes, is an end in itself, though the normal consequence of the -stimulation of these areas is food and water in the stomach. The strange paradox thus exists that behavior is motivated by a mechanism other than the function it serves.

Nature seems to reward the behavior that serves her ends and to punish behavior that frustrates her. Apparently, living things cannot sense and meet their needs directly, apart from this secondary push and pull mechanism. The intelligence of animal behavior then, does not lie in the way that biological ends are served by it, but in the ingenious pain and pleasure "herding" that motivates it.

The instinct of self-preservation is very strong. It is not easily exchanged for a group allegiance to society, tribe,or military unit. Yet techniques for accomplishing this change in attitude are ubiquitous in human cultures

.4 The first episode of possession, trance, or speaking in tongues, associated with a change in attitude, may be gotten only by very severe emotional stress, but once experiencing it, a subsequent response to the beat of the drum, roar of the rhombos, suggestion of the minister or to hymn singing and hand clapping is gotten much easier. A few examples will be given of how effective emotional stress is in converting individuals to religious beliefs.The following quotation is taken from the journal of George Fox (Everyman's Edition, London, p. 106). "This Captain Drury, though he sometimes carried fairly, was an enemy to me and to Truth, and opposed it ... he would scoff at trembling, and call us Quakers. But afterwards he once came to me and told me that, as he was lying on his bed to rest ... he fell atrembling, that his joints knocked -together, and his body shook so that he could not get off the bed; he was so shaken that he had not strength left, and cried to the Lord, and he felt His power was upon him, and he tumbled off his bed, and cried to the Lord, and said he never would speak against the Quakers more, and such as trembled at the Word of God."

Maya Deren, who went to study and film Haitian dancing on a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1949, was too proud to leave when she felt herself responding to the drums; she thought she could fight it, but was overwhelmed. As she recovered from her first voodoo trance she enjoyed feelings of spiritual rebirth. This experience changed her plans for the future as well as her outlook on voodoo. This is what she says in the book, Divine Horsemen: "I would further say, that I believe that the principles which Ghede and other Loa represent are real and true.... It was this kind of agreement with, and admiration for the principles and practice of voodoun which was and is my conscions attitude towards it." (The Living Gods of Haiti. London & New York: Thames & Hudson, 1953, pp. 82-3, 824.)

John Wesley has this to say in his journal: "Some sunk down, and there remained no strength in them; others exceedingly trembled and quaked; some were torn with a kind of convulsive motion in every part of their bodies, and that so violently that often 4 or 5 persons could not hold one of them. I have seen many hysterical and many epileptic fits; but none of them were like these in many respects. I immediately prayed that God would not stiffer those who were weak to he offended. But one woman was offended 'greatly, being sure they might help it if they would, no one should persuade her to the contrary; and was got 3 or 4 yards when she also dropped down, in as violent an agony as the rest." (Vol. 11, pp. 221, 222, Friday, June 1.), 1739.)

Once a person finds himself responding, in spite of himself, he is forced to rationalize his behavior, usually by embracing the creed !he once rejected, because he knows now that there is something to it! There is something toit all right, but it is independent of the creed or religion involved; it is the response of the nervous system to suggestion and strong emotional stress. We may not be able to decide whether we will respond or not, but to a certain extent we can determine how. It is like falling in love. We do fall in love and we should fall in love, but to a certain extent we can decide to whom and the circumstances predisposing us to it. So with religion, we should examine the beliefs before allowing ourselves to be converted or possessed.

The after effects of "possession," religious excitement, or a trance give us some idea why they are sought again and again.

Christian: feelings of being freed from sin and evil dispositions, and starting life anew, love and4. Sargant, William, Battle for the Mind. New York: Doubleday & Company, 1957. compassion for others, communion with God, ecstasy. Yogi: less involved or upset by mundane matters' i.e., living above them, a feeling of oneness with God and fellow man.

Voodoo: more sober, friendly, and co-operative, ecstasy.

Psychoanalytic abreaction: cleanses from pent up, unconscious conflicts; a release from fear and nervous and mental symptoms; is relaxing and sobering.

Peyoti: sobering, feelings of ecstasy and euphoria, gives new meaning to commonplace objects.5,6

To a certain extent the physiological responses in the illustrations above were very similar, yet what the individual experienced in each case was quite different. Maya Deren thought she was possessed by the goddess Erszulie. Captain Drury thought he was in the hands of God. Yogi believe they unite with God when in a trance. In the Peyotist religion, the hallucinations are interpreted as visitations of God. They respond then as though coming into the presence of God. In Pentecostalism, involuntary muscular spasms are interpreted as the possession of the Holy Spirit of God. A person's attitude toward these experiences then is determined by what he thinks he has experienced and he responds the way he is told he should.

A feeling of the certainty or reality of a conviction you hold is no evidence of its truth, for after conversion one can hold just the opposite conviction just as tenaciously and be just as convinced of it. Even completely fictitious convictions can be instilled in the mind under hypnosis. For instance, a student was told under hypnosis that "All German men marry women who are two inches taller than they are." On awakening frorn hypnosis, the student stoutly defended this assertion and even quoted books, authorities, and personal examples to prove it.7

An objective test for the truth of our convictions is needed. But once we are convinced of our "faith," the conservative use of induced emotional states can help us to live an active, productive life in response to what we believe. Working at a job, friendship, marriage, or religious faith without motivation is like trying to drive a car with the brakes on. When employees, students, or members drag their feet it is because their brain is not being stimulated; they are lacking the necessary motivation.

We all chasten our children. We don't like it, they don't like it, but later they are better for it. A mental patient doesn't like having his repressed anxieties pulled out into the open, but if the psychoanalyst succeeds in doing just this, the patient's recovery can be truly dramatic. Military units with a stormy boot-camp and colleges that make it rough on the freshmen have an "esprit de corps" and loyalty that can't be matched by units which heed the per-

An objective test for the truth of our oonvicti~ requires an adequate view of reality. I believe reality is entirely objective, including God. God is not natural law, though He established it and works through it. Hence my knowledge of God is dependent upon my awareness of God's use of natural processes as distinct from natural processes alone.8 Therefore, there can be no absolute knowledge of God, since it is based upon an awareness which is only relative. This does not exclude an absolute revelation of God in nature or in the Bible.

My conscious awareness of reality is variable and artifactual (Locke, Helmholtz9,10). For example it is simpler to assume a single entity for light than to assume a separate entity for every unique interaction of light with my instruments, senses, and the "editing" of my brain. This does not prove the causal identity of the various sensory perceptions of an object, but it does make it probable, which is all science is concerned about. Absolute proof is a philos,oplhic but not a scientific problem. Sensory events that always occurtogether are "linked" in perception and in memory as a single sensory pattern. Their identity, therefore, has a neurological -basis. The relative validity,of my awareness is subject to:

1. comparison with the various modalities of sense: touch, taste, sight, hearing, etc., at different times and under different circumstances.

2. comparison with the conscious perceptions of other people, currently and 'historically. If I were the only one to have a specific experience, I would question it.

Science can provide an objective reality we can all agree upon8 but philosophy can not if it is idealistic, that is, if it assumes that reality exists only in the mind (Hegel, Berkeley).10

An insight into the neurological basis of motivated behavior is given by experiments using rats that have been implanted with electrodes through which they can stimulate their own brains. The rat's rate of self-

5. Huxley, Aldous, The Doors of Perception. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1954.

6. De Ropp, Robert S., Drugs and the Mind. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1957.

7. Wolfe, B. and R. Rosenthal, Hypnotism Comes of Age. New York: Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1948.

8. Sinclair, John, J.A.S.A. 9-4, 12 (1957).9. Crombie, A. C., Scientific American 198-3, 94-103 (1958).

10. Hull, L. W. H., History and Philosophy of Science. New York: Longmans, Green and Co., 1959.

Religious motivation is considered from the point of view of how the brain is stimulated by religious experiences. The similar emotional response gotten from various religions makes it impossible to use this response as evidence of the reality of the beliefs of these religions, though the feeling of certainty or conviction of these beliefs is based on these experiences.

A test for the truth of our convictions requires an adequate view of reality. Science can provide an objective basis of reality we can all agree upon, but philosophy cannot if it is idealistic.